Trump and MAGA haven't been mistreated by the criminal justice system. It has favored them.

Few people get the leniency and preferential treatment the courts have shown Trump and his allies

Donald Trump and allies have complained, over and over again, that the former president and his allies have been targeted, singled out for abuse, and deliberately humiliated by the criminal justice system. They’ve claimed that there are “two tiers of justice” — a strict, unrelenting one for MAGA, and a loose, deferential one for the migrants, rapists, and killers that George Soros-funded prosecutors refuse to punish. Or something like that.

In some cases, they’ve blown mundane, benign stuff into bizarre, sometimes dangerous conspiracies, such as when Trump and right-wing figures claimed boilerplate language on the Mar-a-Lago search warrant about the FBI's authorization to use lethal force was evidence that the Biden administration was trying to assassinate him.

In other cases, they’ve cast recurring, long-existing problems — such as the immense discretion granted to prosecutors, FBI abuse of the FISA system, and the myriad ways the criminal justice system routinely degrades and grinds people down — for abuse and degradation specifically targeted at them. That isn’t uncommon among people who paid little attention to the criminal justice system until it came for them. But few people have the platform Trump does.

As someone who writes and reports on those everyday abuses, it’s been especially surreal to hear these typically wealthy, often very powerful people simultaneously claim that police, prosecutors, and courts are unfair and biased against them and far too permissive and lenient with everyone else.

The truth is that Trump has been getting the criminal justice system’s “platinum door” treatment from the start. His cases are unusual in that he’s a former president. But his status and political position have helped him far more than they have hurt him.

So here are some MAGA world complaints about how they and Trump have been treated, along with examples of how the criminal legal system operates in the real world.

Let’s start with Trump’s complaint that these criminal trials have been a huge inconvenience for him. Some examples:

In 2019, I did some court-watching in Glasgow, Kentucky, a small town about a half hour from Bowling Green (let us never forget those who died in that city’s infamous, fictitious massacre of 2017).

During the criminal court session I was watching, a thunderstorm erupted, and the courtroom temporarily lost power. When the lights went out the man sitting next to me — I’ll call him “Dan” — muttered aloud something about how, if the storm caused court to be delayed, it might finally cost him his job.

When I asked Dan what he meant, he told me that he dug graves for a living. His brush with the law came after a visit to his brother’s house the previous year. Dan’s brother had a drug problem. While Dan was visiting, the police showed up over an alleged parole violation by his brother. The police searched the house and found some meth. Dan told me that his brother had a criminal record, mostly related to drugs, but because no one claimed the meth, the police arrested and charged everyone in the house under the sketchy legal theory of “constructive possession.”

Dan told me that the police offered to drop the charge if he agreed to become an informant. He refused. Instead of bail, he was released pending trial after agreeing to wear an ankle monitor. It cost $200 per month, which Dan had to pay. And unlike bail, Dan wouldn’t get that money back, even if he was acquitted.

That particular afternoon was Dan’s fourth time in court for the charge. He’d had to take off work each time. He feared the power outage would mean another delay, which would mean another trip to court. His boss was losing patience.

As we talked, a woman behind us spoke up. I’ll call her “Angela.” She, too, was in court on a constructive possession charge. Angela was a house cleaner, and was arrested when police raided a client’s home while she was cleaning. Her client’s teenage daughter was allegedly selling drugs. This was Angela’s third time in court on that charge.

I can’t vouch for the truth of either story, but public defenders in Barren County told me that “constructive possession” charges are fairly common in that court, and that what Dan and the woman told me were similar to what they’d seen with other clients.

Typically, people facing criminal charges have to show up when court begins, then sit for hours until their case is called. They’re required to take off work, or find someone to watch their kids. And those are merely the people lucky enough to be released before trial. In many courts, they aren’t allowed to have cell phones. Over the last few years, I’ve watched dozens of people wait in a courtroom, staring at the wall for half a day or more, only to learn that their case has been continued, so they'll have to do it all again in a month.

I don’t know if any of them had to cancel a political rally, but many have certainly been fired, missed doctor’s appointments, or lost other opportunities. I suppose it’s possible that a judge at some point let a defendant charged with 34 felonies delay a trial to attend a graduation ceremony, but I imagine if you asked a public defender if that’s a regular occurrence, you’d need to set aside some time for the laughter to die down.

Incidentally, Trump was permitted to attend his son’s graduation.

MAGA has also complained about the tactics the FBI agents used when serving the search warrant on Mar-a-Lago:

I’ve been writing about aggressive police raids for over 20 years. I think about Trump’s shoe complaint often. It’s just so incredibly stupid.

The FBI gave Trump’s Secret Service detail a heads-up that they were coming. They deliberately conducted the search when Trump would be out of town, specifically to save him embarrassment. Contrast that to what happened to a whistleblower like William Binney, who tried to point out problems at the NSA by going through internal channels. FBI agents raided his home unannounced, entered without authorization, and pointed their guns at him after finding him in the shower.

But I’ve thought about Trump’s “they’re tracking dirt on the rug” complaint most often while working on a story I’ve been reporting for a couple years now, and hope to publish soon. It’s about a woman in Alabama who in 2019 was shot and nearly killed during an early morning raid on her home by a joint federal/local task force. The task force was serving an arrest warrant for a man who, six months earlier, had been arrested for “attempted possession” of an illicit substance — he had bought a small amount of fake meth from an informant. It’s about as low level a drug crime as you can get.

The man the police were looking for did not live at the home they raided, and hadn’t for a couple of years. They hadn’t bothered to check. Worse, at the time of the raid he was already in police custody, and had been for months. They didn’t check that, either.

Though she did nothing wrong, this woman now faces hundreds of thousands of dollars in medical bills. Instead of, say, showing some contrition and remorse, the state and local governments involved in the raid — along with the federal government — have spent the last five years fighting her in court by pursuing immunity claims.

After they realized their mistake, the task force made no effort to repair the damage they had done to the home. The woman’s now-husband told me that after trying in vain to get someone to clean up the mess, some friends and family finally came over to help. They brought food and threw a “party” to sweep up the shattered glass and board up the splintered doors — and to clean his then-fiancee’s blood from the floor.

I can’t say for sure if the officers took off their shoes before shooting this woman and tossing her home. But I suspect they did not.

The far right has also suggested that Robert Mueller’s office may have tipped off the media to maximize publicity around the raid:

Tipping off the press about a pending arrest is a time-honored tradition among publicity-seeking prosecutors. The amusing thing about this complaint is that the carefully staged perp walk as a publicity stunt is a technique first popularized by . . . Trump personal attorney and bag man Rudy Giuliani.

But it happens more routinely, too. The Alabama case I mentioned above was part of a “sweep,” in which the task force served dozens of warrants, all for low-level drug offenses. Before the operation, the local sheriff’s office released a statement to local media, complete with suggestions that they refer to the sweep with fun names like “Santa’s Naughty List.” They also invited local press to accompany them on the raids.

We now know that Mueller’s office did not tip off CNN. The network’s reporters had staked out Stone’s house after noticing unusual activity in court fillings from Mueller’s office. It was just good reporting.

MAGA world has also been critical of how search and arrest warrants were served on other Trump-adjacent personalities.

The FBI and other federal agencies routinely conduct volatile, aggressive raids on people suspected of nonviolent or low-level crimes. Earlier this year, for example, the ATF conducted a pre-dawn raid on a Little Rock airport manager suspected of violating a vague federal law distinguishing firearms dealers from gun hobbyists. The man fired on the agents, likely thinking they were criminals. They killed him.

A few months ago, heavily-armed Georgia police raided the headquarters of a charitable bail fund, accusing the group of money laundering and fraud, charges that are dubious at best, and that require prosecutors to classify crimes like vandalism, unlawful leafleting, and trespassing as “terrorism.”

Prior to major political conventions, federal law enforcement officials have made a habit of preemptively raiding activists on flimsy suspicion of being “extremists” or associated with “terrorism.” Most of the people raided were never charged with a crime. And raids on people vaguely suspected of subversion-related crimes are practically part of the culture at the FBI.

As for Arpaio, he once sent a small army of cops to raid a guy accused of cockfighting. That raid ended with actor, cosplaying cop, and serial sex pest Steven Seagal driving an armored vehicle into the poor guy’s living room.

And of course, we haven’t even reached the most common targets of aggressive warrant service tactics — people accused of low-level drug crimes. If you’ve read my work at all over the years, you already know many of the names on that list of victims — Breonna Taylor, Kathryn Johnston, Donald Scott, Clayton Helriggle, Alberto Sepulveda, Alberta Spruill, and most recently, 16-year-old Randall Adjessom.

But here are just a few examples within a year or so of when news broke about the Manafort raid.

A couple months after the Manafort raid, a Kansas couple lost their federal lawsuit against police officers who wrongly raided their home after mistaking wet grounds of loose-leaf tea for marijuana.

Also right around the time of the Manafort raid, police in Toledo, Ohio shot and killed a man’s dogs during a drug raid on his home. They found a single pill — for high blood pressure.

A year before the Manafort raid, the ACLU sued the DEA after agents pointed their guns at the heads of children while serving a low-level drug warrant on their home.

That same year, the town of Framingham, Mass. settled with the family of Eurie Stamps, an innocent man who was shot and killed by a SWAT officer during a raid on his home. They were looking for Stamps’s stepson for drug crimes.

Meanwhile, two Detroit women who were mistakenly raided and actually manhandled by masked DEA agents finally saw their lawsuit dismissed. The reason: The agents refused to provide their names or badge numbers, and the courts refused to compel the DEA to name them.

At about the same time, an FBI-led raid team terrorized occupants of a home in Quincy, Massachusetts during a drug raid, found nothing, then refused to talk about it.

Here too, it turns out that the right-wing victimization complex is especially misinformed. Trump’s allies weren’t even treated the same as everyone else. They were treated quite a bit better. The raid on Roger Stone was not unusual, nor was it violent, despite Stone’s history of associating with violent groups and vague threats against elected officials. Armed FBI agents came to his home, knocked on his door, waited for him to answer, and arrested him when he did.

Similarly, despite early reports at the time, the arrest warrant for Paul Manafort was not served with a no-knock raid, either. Nor was it served “pre-dawn.”

Then there’s January 6th. We’ve seen a constant stream of complaints and accusations that the January 6th rioters have been singled out for abuse, especially when compared to those accused of rioting and looting during the George Floyd protests.

About 70 percent of people arrested and charged with January 6th-related crimes were released on bond or under their own recognizance, including everyone charged with crimes that would qualify as “peaceful protest,” such as trespassing. Just 25 percent of federal criminal defendants are released pre-trial overall.

If we factor in both state and federal courts, the number of people routinely detained while awaiting trial in this country is so large that there are actually more people behind bars who have yet to be convicted than people who have. But 7 in 10 January 6ers were released.

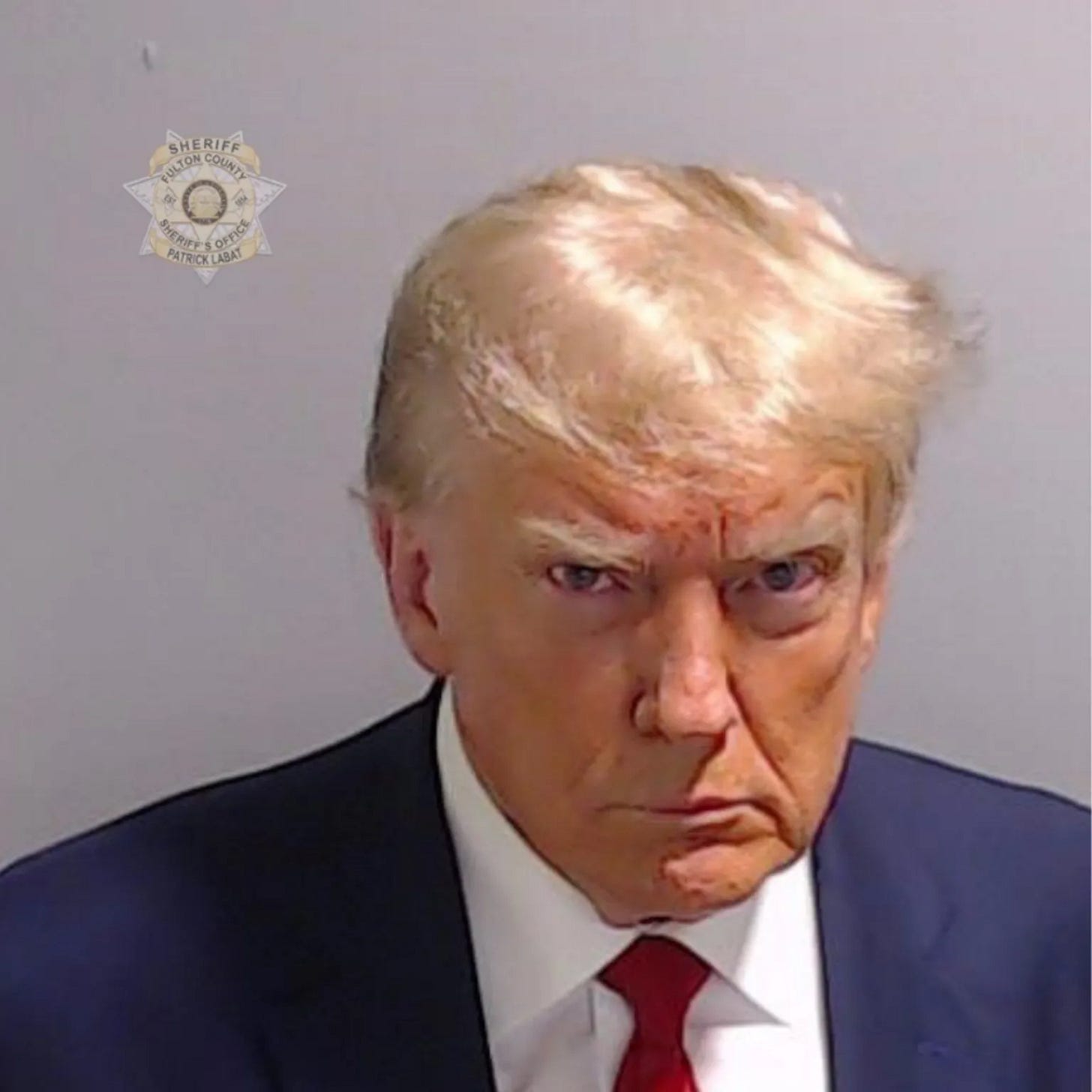

It is true that conditions in the D.C. jail are terrible. This is true of most jails. They’re horrific, under-supervised, unsanitary, and hellish, and have astronomical rates of suicide (far higher than prisons). When Trump was booked at the jail in Fulton County, Georgia, he complained that the facility was “poor and disgraceful,” adding, “It’s worse than you could even imagine. It’s violent. The building is falling apart."

But Trump was quickly booked and released. He didn’t spend any time in an actual jail cell. It also probably won’t surprise you that his complaints about the jail didn’t extend to much empathy for the people still languishing in it.

Hundreds of people were held at Fulton County Jail for more than 90 days because they had yet to be formally charged or could not afford to pay the bail bond required for their release, according to a September 2022 report from the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU).

The report also found 117 people had waited in jail for more than a year because they had not been indicted; 12 had been held for two years for the same reason.

The Fulton County Jail is at 2.5 times its capacity. At the time Trump was booked, in August 2023, six people had already died that calendar year.

Of course, the Fulton County jail and many others may be “poor and disgraceful” and “violent,” but that hasn’t stopped Trump and his supporters regularly lambasting prosecutors for letting people out of those jails while they await their trials.

All of the January 6th defendants who were not released prior to trial were charged with serious felonies. I happen to think many of them could probably have been released without much risk. But in general, federal public defenders have made clear that the federal courts have been far more likely to release Capitol rioters pre-trial than other defendants.

Speaking of which, the D.C. federal public defender’s office went all out to make sure that January 6ers received a robust defense. They ramped up staffing, and enlisted attorneys from other federal offices to help. That’s commendable and speaks to the professionalism of public defenders, especially given the right’s general contempt for public and criminal defenders, and some Trump supporters’ baseless attacks on the defenders in these cases in particular.

Incidentally, the Republican-controlled Congress has since slashed funding for federal public defenders, forcing many offices — including the one in D.C. — to lay off staff and implement furloughs.

We can contrast the extraordinary efforts to make sure the January 6ers were well-defended to the ongoing crisis in public defense I’ve been documenting on this site. There are parts of the country where people sit in jails for weeks or even months before ever seeing a lawyer. Some meet their attorney for the first time just minutes before they’re due in court. Many public defenders have no access to investigators. Most are severely overworked.

As for alleged sentencing disparities, here’s what an analysis by The Intercept found:

In 82 percent of the 719 January 6-related cases that have been resolved, and in which the defendants have either pleaded guilty or been convicted, judges have issued lighter sentences than federal prosecutors requested, the analysis of Justice Department data through December 4, 2023, shows. They imposed the same sentences sought by prosecutors in just 95 cases and harsher sentences in only 37.

The publication also found that judges appointed by Biden were actually more lenient with January 6th defendants than judges appointed by Trump, and that Judge Tanya Chutkan, who is overseeing Trump’s overthrowing-the-election trial, and whom he has regularly accused of political bias, sentenced Capitol riot defendants to less than prosecutors’ recommendations in more than half the cases over which she presided.

Finally, Ramaswamy’s complaint that “antifa” and “BLM” protesters received more favorable treatment than January 6ers also lacks any real evidence. Before I get to that, let’s just stipulate that it’s silly to try to compare the two. The protests took place all over the country and went on for months. The Capitol riot lasted a few hours and was limited to one location. The Capitol is also under federal jurisdiction, while most of the George Floyd protests fell under the jurisdiction of state and local prosecutors, save for any that resulted in damage to federal property.

But Ramaswamy and others have made this claim, so let’s look at what we know: The federal government alone arrested about 6,000 protesters in the summer of 2020. Around 1,500 were charged. That’s five times more people than were arrested at the Capitol, and about 25 percent more who faced charges.

Nationwide, around 14,000 George Floyd protesters were arrested within the first month of demonstrations. The total arrests of racial justice protesters arrested in cities like Los Angeles and New York alone — just in the first month — exceeded the total number of January 6th arrests.

An AP analysis of 100 George Floyd protesters charged with federal crimes including rioting, arson, and conspiracy, found that they received an average sentence of 27 months, far longer than the median January 6th sentence of 120 days.

Another report looking at 300 people charged with federal crimes stemming from the 2020 protests found that nearly 90 percent of those cases could have been charged in state court, where they would have received more favorable treatment. The Trump administration pressured federal prosecutors to charge protesters in federal court — and to pursue the most aggressive charges possible — for precisely this reason.

I haven’t been able to find a national review of how all the state and local cases from 2020 have been charged and resolved, but there’s anecdotal evidence that they’re still meandering through the courts, interrupting lives along the way. We also now know from resulting lawsuits that a large percentage of the protest arrests were unlawful.

So the argument that the proportionately small percentage of protesters who destroyed property or injured others during the George Floyd have been permitted to “roam free” just isn’t remotely true. Neither is the argument that January 6ers were treated more harshly than racial justice protesters. They’ve been treated quite a bit better, despite the clear moral differences between protesting against racism and police brutality and storming the Capitol to overturn the results of a valid election.

In the end, Trump has been treated far better and received more preferential treatment than just about anyone ever ensnared in the criminal justice system. He’s the only person in U.S. history to have his criminal case appear before a judge he appointed — and one he could promote to a higher court should he retake the White House. He’s also the only person in U.S. history to have his criminal case appear before the U.S. Supreme Court after having appointed a third of that court’s justices — an advantage that appears to be working out well for him.

Just for comparison, let’s look at how the classified documents case compares to similar cases against non-former presidents. The Justice Department became aware that Reality Winner had leaked a single classified document to a media outlet — a document she believed served an important public interest — in May 2017. She was arrested the following month. By August 2018, 16 months later, she had been sentenced to 5 years in prison.

Trump was indicted for hoarding around 200 classified documents, lying about them, refusing to turn them over, and then obstructing the government’s attempts to recover them. Whatever his motivation was for all of this, it definitely wasn’t whistleblowing.

Trump illegally took the documents in January 2021. The first indication that the government became aware of them was in May of that year. The National Archives then gave Trump repeated warnings. Instead, he showed off top secret documents to Mar-a-Lago visitors — and boasted about their secret-ness as he showed them off. The FBI didn’t open an investigation until March 2022. The search of Mar-a-Lago didn’t take place until the following August. Trump wasn’t indicted until June 2023. It has now been 37 months since the government became aware of Trump’s 200 documents, and it’s unlikely that his trial will happen any time soon.

Yes, the two cases aren’t exactly the same, most notably because Trump is a former president. But the idea that he is being vindictively persecuted is absurd. His power and status are affording him consideration no one accused of similar crimes would ever receive.

Trump has also somehow managed to spend the entirety of two civil trials and a criminal trial attacking and occasionally threatening judges, witnesses, and prosecutors without being jailed for it. At risk of stating the obvious, there aren’t many criminal defendants who can say they were found in contempt of court 10 times in a single trial without being jailed.

At — again — risk of stating the obvious, most people facing criminal charges also don’t have the most powerful public officials in the country holding press events outside their trials to denounce the judge and prosecutor. Most don’t have chairs of congressional committees threatening to subpoena the prosecutors who have charged them. And most don’t have sitting U.S. senators issuing vague threats against the judge who currently considering their sentence.

For most people, a record with 36 felony convictions would be a significant barrier to just about anything they undertake for the rest of their lives. But other than what appears to be a slight ding to his poll numbers, Trump’s convictions seem unlikely to hurt him at all.

In many states, for example, anyone convicted of a felony is prohibited from holding public office. But there are no such restrictions on running for the most powerful public office in the country.

People convicted of crimes related to dishonesty and fraud specifically (as Trump was) are also disqualified from most civil service positions in the federal government — and from winning contracts with many government agencies. But such convictions do not bar you from becoming president, the office that oversees all of those positions and contracts (and if, Trump gets his way, will have the power to fire huge swaths of the civil service for insufficient loyalty).

Trump’s convictions and charges — especially the pending charges for mishandling classified documents — would also bar him from any position that requires a national security clearance. But you don’t need a security clearance to run for president. That’s probably a good thing, but in this case it means that while Trump’s convictions and pending charges would otherwise disqualify him from any job that require access to any classified information, they don’t bar him from the one job that gives him access to all of it.

Trump also won’t be disenfranchised, one of the more profound indignities we impose on people with felony convictions. In nine states, convicted felons lose their right to vote for life. In another 38, they can regain the right after serving their sentences and paying their fines. Some states specifically disenfranchise people convicted of felonies related to fraud, deceit, or elections.

Trump also resides in Florida, a state that has been historically punitive to voting rights for felons. But for out-of- state convictions, Florida tends to defer to the laws of the state where the conviction happened. And fortunately for Trump, New York restores the rights of felons to vote upon completion of their prison sentence. It’s the sort of comparatively lenient policy that Trump and his party have adamantly opposed.

Florida also gives its governor the power to restore any individual resident’s right to vote. Ron DeSantis has made it clear that he’d use that power to ensure that Trump is never disenfranchised. DeSantis not made that sort of promise to any other Florida resident. In fact, this is the same governor who staged cruel media spectacles in which he sent law enforcement officials to arrest and humiliate people who mistakenly voted under Florida’s confusing re-enfranchisement law.

People with felony convictions also often face difficulties traveling overseas. Currently, 38 countries bar entry to foreigners with a felony record. While it’s possible that a country or two might bar Trump from entering to make a political statement — perhaps to contrast his own behavior with his false and bigoted rhetoric about the criminality of immigrants — it seems unlikely that most countries would be willing to risk the consequences of angering the vengeful leader of a major political party of the most powerful country on earth. It’s doubtful that Trump will have much problem traveling overseas — as either a sitting president or a former one.

Occupational licensing restrictions are an especially onerous barrier for people with a criminal record. In many states, a felony conviction can prevent you from becoming a barber or hairdresser, lawyer, teacher, radiology tech, athletic trainer, cosmetologist, banker, insurance salesman or adjuster, doctor, nurse, plumber, electrician, accountant, real estate agent, HVAC specialist, and numerous other professions. These restrictions limit the ability of people with criminal records from earning a living. People with criminal records substantially less money after their convictions, and their earning potential remains limited over the course of their lives.

There are no such restrictions on becoming president, or leading a political party.

People with criminal convictions also typically struggle to pay court fines and fees, probation or parole fees, child support, and private debts accumulated while they were incarcerated. It can be difficult to find housing, and they’re far more likely to experience homelessness.

Trump himself faces significant fines and fees. He owes $450 million to the state of New York for crimes committed by his company, and $90 million to E. Jean Carrol after a jury found him liable for defaming her after he sexually assaulted her. Trump also has a habit of not paying his creditors, though in his case it’s usually more a matter of not wanting to pay than the inability to do so.

Still, unlike others with felony convictions, Trump will not end up homeless or destitute. It’s unlikely he’ll even need to alter his lavish lifestyle.

People with felony records can have difficulty accessing public assistance programs like food stamps, student loans, or government subsidized housing, sometimes due to specific policies, and sometimes due to the decisions of the people who administer these benefits. There are of course no such restrictions on the most lavish government-subsidized housing in the country — the White House. But more importantly, Trump himself has received hundreds of millions of dollars in government handouts over the years, mostly in the form of subsidies and tax breaks for his real estate projects. Fortunately for him, convicted felons and their businesses aren’t barred from most of these corporate welfare programs.

Since he became president, Trump has also been the recipient of another type of public funding unavailable to most people — the $100+ million in payments foreign governments have made to his hotels, residential buildings, and golf clubs. His criminal record obviously doesn’t prevent such patronage in the future, though any foreign agent wishing to shower his businesses with cash will need to find one that isn’t in New York — Trump is currently prohibited from operating a business there.

Trump was convicted of the least serious class of felonies in New York. Most first offenders for that class of crimes aren’t sentenced to prison time. On the other hand, contrition and remorse are an important part of sentencing. It seems pretty certain that anyone else who had just been convicted of 36 such felonies who was also cited 10 times for contempt, publicly and favorably compared themselves to Al Capone, and who not only showed zero remorse but essentially vowed to commit more crimes in the future would probably find themselves behind bars pretty quickly.

Still, because of who Trump is, most legal observers don’t think Judge Juan Merchan will give him prison time. Even if he does, Trump will likely be permitted to delay the pending his appeal, which is likely a way to avoid the political implications of incarcerating him during a heated presidential campaign without admitting as much. Needless to say, most people don’t get this sort of consideration.

Trump is more likely to get probation. But that, too, will be unlike any probation anyone has ever experienced. Probation or parole after a felony conviction typically comes with restrictions on interstate movement, instructions not to associate with other people charged with or convicted of felonies, unannounced searches, regular meetings with a probation officer, and other indignities. Some parole and probation officers (including in New York) are also notoriously petty, and in many places improperly incentivized to violate people for minor offenses.

Trump may face at least some of those restrictions on paper, but it’s difficult to see how they’d be enforced. It’s easy to imagine Trump disregarding his probation by skipping appointments; consulting with the long roster of convicted felons in his orbit, or disparaging or threatening witnesses in his other cases at rallies or on social media.

It’s harder to imagine a probation officer citing him — and a New York court then jailing him — for any of that. It’s hard to imagine putting any probation officer in that position, given Trump’s followers’ habit of harassing and threatening anyone they’re told has wronged him. Such a scenario seems especially unlikely as we enter the homestretch of a presidential campaign. Should Trump win in November, it’s harder still to imagine any judge or probation officer holding him accountable once he’s president-elect, and certainly not after he has taken office.

Trump won’t escape every consequence of a felony conviction. He will have to give up his guns. But he has never claimed to be a hunter or sport shooter, and with lifelong Secret Service protection, he doesn’t need to worry about personal security. It’s also possible that his New Jersey golf clubs could lose their liquor licenses, though his lawyers are likely to find a workaround.

Over the years, I’ve interviewed more people treated unfairly by the criminal justice system than I can count. They often say that the experience changed them. It made them more empathetic, less trustful of police and prosecutors, and more willing to entertain the notion that the system sometimes gets it wrong. Most understand that any system capable of the injustice inflicted on them has certainly done the same or worse to others. Powerful people who encounter the justice system can be particularly effective agents of change.

But that isn’t going to happen here. That’s partly because Trump has experienced only the most glancing of consequences from his criminal convictions. But it’s also because MAGA revels in victimhood. Conceding that the system is fundamentally unfair would merely make Trump one victim among many. The false narrative that courts and prosecutors are hellbent on targeting him and his supporters — while showing outrageous leniency toward scary drug dealers, rapists, and killers — only amplifies the outrage and victimhood.

This narrative also lets Trump and his allies call for more punitiveness and retribution even as they rail against the way the justice system has treated him and his allies. Trump can call for the execution of alleged drug dealers even as he continues to take credit for pardoning one, and despite reports that the Trump White House was handing out controlled drugs like parade candy. His high-profile supporters can demand he not be prosecuted for fraud or plotting to overthrow an election while demanding more punitive sentences for shoplifters, or people who operate bail funds.

MAGA’s beef with the system isn’t that justice has been weaponized, it’s that it has been weaponized against them. Their answer isn’t to insulate the system from politics, it’s to ratchet up the politicization, then aim it at their enemies.

One stark difference between Trump and everyone else with a felony record is that while most everyone else lives in perpetual anxiety about what to tell employers, neighbors, or potential paramours, Trump’s convictions were very public, so hiding them was never an option. But because of his power and position, the public nature of his charges has been far more of an asset than a burden. His convictions made him the ultimate victim. They let him cast himself as the mob boss he’s always aspired to be. And they motivated his supporters to give him their money, helping him overcome a significant fundraising gap with Joe Biden.

Most people struggle daily with the consequences of a felony conviction. Trump gets to wear his record like a garish cockade.

I tried to have this conversation, as a career public defender, with a MAGA supporter the day after the Trump criminal verdict. He ended our friendship the next week. This work is so important, thank you.

Magnificent piece of work. Thank you.