Back in 2018, a civil rights attorney sent me Ring camera footage of a drug raid in Little Rock. The raid was on the apartment of Roderick Talley. It was unlike any drug raid video I’d seen, in that the police used explosive to blow the door off its hinges. The door flew several feet across the room and landed on the couch where Talley was sleeping. The footage then shows the officers watching the video back and celebrating while Talley is restrained to a chair. Talley was arrested, but prosecutors would later drop the charges due to insufficient evidence.

Here’s a local news report that includes video of the explosive raid:

When Talley obtained the search warrant and affidavit that led to the raid, he was baffled. The affidavit stated that Talley had sold heroin to an informant. Detective Mark Ison* claimed they had thoroughly searched the informant, sent him to Talley’s home, and that he had never left their sight. Ison claimed to have observed the door to Talley’s apartment open, and saw the two men have a conversation. Ison then claimed the informant returned with heroin, which he said he’d just bought from Talley.

(*Quick aside: Prior to publication of my original investigation for the Washington Post, a Little Rock city attorney convinced the Post’s legal team to leave Ison’s name out of my article. The attorney argued that as a narcotics officer, Ison’s identity should be protected. I thought then and still think now that this is absurd, for four reasons. First, Ison wasn’t working undercover. He was sending an informant to conduct the drug buys. Second, if he were to go undercover, Ison presumably wouldn’t be using his real name. Third, he was caught lying on a sworn affidavit, which I’d argue suggests he should no longer be a narcotics cop in the first place. The job of the media is expose lying cops, not to protect them. Finally, fourth — and most amusingly — at the time if you Googled “Mark Ison” and “Little Rock,” the top hit was a local TV news report about heroin in Little Rock in which Ison appears on camera and is identified as an officers who “patrols the streets for drugs.” )

Ison’s entire affidavit was a lie. Talley’s Ring camera does show an informant come to his door. But Talley wasn’t home at the time. The informant knocked on the door, waited, and left. There was no conversation, and no exchange of money or drugs. Talley would later submit an open records request for other drug raids carried out by the same officers. In 2018, he sent me the 105 warrants and affidavits he obtained from that request. I reached out to several people named in those warrants, and learned that many of them had been visited by the same informant. Those who were home at the time say he came in, made some small talk and left. No talk of drugs. They too would later have their doors blown off their hinges. And they too would be utterly baffled when they’d read in the sworn affidavit about an alleged drug transaction that never happened.

I’ll write more about Talley and these other cases in future posts. But for this post, I’d like to focus on Hugh Finkelstein, the judge who signed the warrant in Talley’s case. Most judges just don’t scrutinize search warrants, even warrants for extraordinarily violent and volatile searches that involve no-knock raids and “dynamic entry.” And police quickly learn to avoid the few judges who do.

That was no different in this case. These cops used the same lying informant, over and over, and there’s no evidence that Finkelstein or his predecessor, retired judge Alice Lightle, ever questioned them about it. Perhaps that isn’t surprising. Judges rarely question police about the reliability of their informants. But they should.

But as I looked through the affidavits Talley sent me, I noticed another problem. In requesting permission to conduct no-knock raids, Little Rock drug cops were using the same, word-for-word boilerplate language about exigent circumstances.

In 1995, the Supreme Court ruled in Wilson v. Arkansas that generally speaking, under common law tradition, the police must knock and announce themselves before forcing open the door to a private home to serve a search warrant. But the court did carve out some exceptions, called exigent circumstances. If they can provide evidence that a particular suspect would be a threat to flee, harm police or others, or destroy evidence if police knocked and announced, a court can issue a no-knock warrant.

Police agencies responded to that ruling by simply using boilerplate language stating that all drug suspects are a threat to flee, harm police or others, or destroy evidence. So two years later in Richards v. Wisconsin, the court made it clear — police must show evidence that the particular suspect for whom they’re seeking the no-knock warrant is a threat.

From the opinion in Richards:

If a per se exception were allowed for each category of criminal investigation that included a considerable--albeit hypothetical--risk of danger to officers or destruction of evidence, the knock and announce element of the Fourth Amendment's reasonableness requirement would be meaningless.

Thus, the fact that felony drug investigations may frequently present circumstances warranting a no knock entry cannot remove from the neutral scrutiny of a reviewing court the reasonableness of the police decision not to knock and announce in a particular case. Instead, in each case, it is the duty of a court confronted with the question to determine whether the facts and circumstances of the particular entry justified dispensing with the knock and announce requirement.

In order to justify a "no knock" entry, the police must have a reasonable suspicion that knocking and announcing their presence, under the particular circumstances, would be dangerous or futile, or that it would inhibit the effective investigation of the crime by, for example, allowing the destruction of evidence.

This is not a difficult burden to meet. You only need to show that the suspect is armed, or has security cameras, or has bars on the door. Even an informant’s word that the suspect stores his drug supply near the toilet has been deemed sufficient.

Unfortunately nine years later, in Hudson v. Michigan, the court ruled that even when police do violate the knock-and-announce rule — that is, even when they do perform an illegal no-knock raid — the Exclusionary Rule no longer applies. So police can still use any evidence collected in that raid against the suspect in court. The ruling in Hudson took away the only real incentive for police to abide by the knock and announce rule.

At the time, many of us predicted that the court had basically made knock-and-announce unenforceable, and that police were now free to conduct dangerous and illegal no-knock raids with no consequence.

That’s exactly what has happened. Of the 105 warrants I reviewed from Little Rock, LRPD officers requested a no-knock raid in 103. Of those 103, their request was granted in at least 101 (two were missing the page with the judge’s instructions). Of those 101, the police provided particularized information about why that suspect met the exigent circumstance exception in just eight. This means that at least 93 of the 103 no-knock warrants I reviewed were illegal. (I’ve since learned that the LRPD likely conducted many, many more no-knocks than the sample of warrants/affidavits I obtained.) We’d later learn that LRPD policy dictated that every search warrant be served with a SWAT team.

The warrants I reviewed covered the three year period between 2016 and 2018. Lightle signed all the warrants from 2016 through April of 2017. Finkelstein signed the rest.

I called both judges for my 2018 article in the Washington Post. Both were defensive. Lightle was more willing to talk to me, since she was by then retired.

From my 2018 article:

Lightle moved to Colorado after her retirement, but I was able to reach her over email. “I signed many many warrants for drug cases,” she wrote. “Many more than the 100 that you have in front of you. More like thousands. And yes, I know that I signed many warrants that were NOT for a no-knock.”

Of course, there are lots of reasons that courts issue search warrants other than drug crimes. But the warrants I reviewed were in response to Talley’s request for all documents related to cases involving members of the LRPD’s drug unit over a period of 20 months. All but two of these warrants requested permission to conduct a no-knock raid. And all but two were granted.

I asked Lightle whether she recalled granting no-knock warrants that lacked particularized information for each suspect. She replied, “With every affidavit, I specifically questioned the officer/detective about the particular circumstances for any warrant. I never signed a warrant without knowing exactly what was going on in each circumstance. Even when a warrant was signed by electronic means that was prefaced by conversation between the detective and myself usually by phone. I take the no-knock requirement seriously and upon the provision of the probable cause I was satisfied that it was warranted.”

But if Lightle based her to decision to grant a no-knock warrant on information from a phone call, that information should have been appended to the affidavit. “There’s certainly no law against supplementing search warrant affidavit with additional information,” says Fourth Amendment scholar and University of Michigan law professor David Moran. “But that information must be documented. If it came from a conversation with a police officer, that officer needs to be sworn, and the conversation should be transcribed.” If the no-knock warrants Lightle signed did include such addendums, they weren’t included with the documents the LRPD provided in response to Talley’s open-records request.

Lightle was insistent that she gave no-knock warrant requests adequate scrutiny. “I would take issue if you are saying this was some type of ‘assembly line’ process. I was a conscientious judge and I looked carefully at what came before me and why certain premises were to be searched . . . I never signed a warrant without knowing the totality of the circumstances as presented to me.”

There’s really no way around this: Lightle was either signing warrants with boilerplate language about no-knock raids, which would be illegal, or she was signing warrants based on extra information officers gave her that was not included in the affidavit, which would also be illegal.

Finkelstein would only say two things on the record: First, he insisted that the warrants with the boilerplate no-knock language were not illegal. (They were, and the fact that he thought otherwise ought to be disqualifying.) And second, in defending himself from the accusation that he rubber stamped warrants, he said he frequently rejected warrants for lacking probable cause, though he couldn’t recall any specific instance in which he’d done so.

The Supreme Court created an important rule in Wilson, but in Hudson then removed the only real means of enforcing it. Consequently, cops can now violate the rule with impunity. And not just in Little Rock. We learned it was also happening in Louisville after the death of Breonna Taylor, and in South Carolina after the shooting of Julian Betton. I’d imagine we’ll discover it’s happening elsewhere when journalists or civil rights attorneys start scrutinizing a department’s warrants and affidavits after next inevitable no-knock raids that ends with the death of an innocent person.

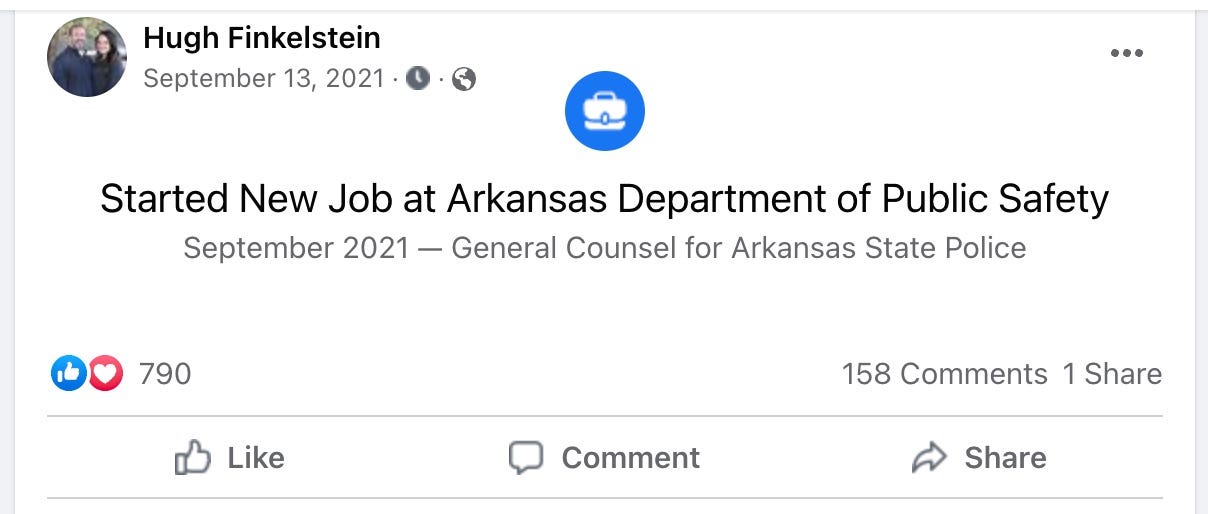

But let’s get back to Judge Hugh Finkelstein. Here’s a judge who repeatedly shirked his duty to protect the Fourth Amendment, who repeatedly authorized police to conduct illegal and dangerous no-knock raids, and who, when confronted with the fact that those raids were illegal, insisted that they weren’t. What’s Finkelstein doing now?

In 2020, Finkelstein ran for the judgeship of a higher court. He lost by about four points. But Finkelstein has since found new employment, and it’s a job that’s probably better suited to his interests and biases.

From his Facebook page:

My biggest issue with receiving this newsletter in my email inbox is that I get infuriated every time. Every single time. Thanks for shining the light on these abuses of power.

Love Radley balko