Confused about conflicting claims about crime? Need some backup for Thanksgiving arguments with your law-and-order relatives?

Here’s The Watch’s guide to crime and how it’s being exploited for this week’s midterms — which claims are valid, which are nonsense, and what we still don’t know.

Let’s jump in.

Murders are surging

True. Murders rose significantly in 2020, and then again in 2021, though at a much slower rate. There are some indications that homicides have fallen so far in 2022, though we'll almost certainly end the year with a much higher homicide rate than before the pandemic.

Crime is surging overall

Mixed. Let’s look at the last three years separately.

While murders did spike in 2020, property crime fell that year, as did the overall crime rate. According to FBI figures violent crime overall also increased, but at a far lower rate than the murder rate. But according to our other main source of crime stats, the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS), overall violent crime did not go up, though the NCVS does not track homicides.

As for 2021, while homicides increased slightly from 2020, according to the FBI, overall violent crime dropped by 1 percent. Property crime also dropped.

So far, it looks like 2022 may reverse the trends of the previous two years. Homicides will likely be lower, while most other types of violent crime will likely increase.

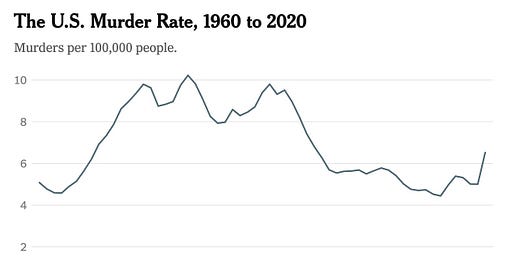

Murders are at an all-time high

False. While a number of cities did set murder records in 2021, some cities actually saw a drop in murders. Nationally, murders increased by about 30 percent from 2019 to 2020, then by about 4 percent again in 2021.

Some have called this the largest increase in more than a century, and as a percentage increase, that's technically true. But it's important to remember that these increases came off of record low murder rates in the mid-2010s. Any increase from a low base number is going to seem large when expressed as a percentage.

The U.S. murder rate peaked in the early 1990s, then began a steep 10-year drop, followed by a more gradual drop from 2006 to about 2014. The 2020 increase put the national murder rate back to where it was in the late 1990s, toward the end of that initial drop. This means that 2020 and 2021 represented a 20 year-high in the murder rate, but both were still well below the rates of the early 1990s.

This is not to say the increase in murders is not significant or important. It is to say that historical context matters, too.

The surge in murders has primarily come in places run by Democrats, or with progressive prosecutors who are lenient on crime

False, as I’ve already explained here.

The homicide surge was caused by de-funding the police

False.

First, if de-funding did cause the spike in murders, we should also have seen spikes in crime across the board. It’s unlikely that a cut to funding for police would lead to an increase in murders, but not, property crimes or burglaries. But that’s what happened nationally in 2020 and 2021.

Second — and more importantly — the police haven't been de-funded. A handful of cities made marginal cuts to police budgets. A couple cities also eliminated controversial “elite” police units that have tended to court controversy. In others, a wave of retirements may have reduced overall police numbers. Police groups and their defenders have suggested the retirements were a form of "de-policing,” in that cops were leaving the profession out of frustration. But they could also have been spurred by pension-driven incentives that made it optimal for them to retire the year after working overtime at protests.

In a few places, most notably St. Paul and Portland, somewhat significant cuts to police budgets did occur contemporaneously with record increases in homicides. And it would be foolish to suggest a large, sudden, highly-publicized reduction in police officers on the street wouldn’t have at least some effect on crime.

But correlation isn't causation. Indianapolis, Baton Rouge, Mobile, and Albuquerque, among other cities, saw record-high, or 20-year-high murders in 2021 despite increasing their police budgets. Atlanta saw a 30-year high in homicides last year (and is on an even deadlier pace this year) despite a whopping 18.5 percent increase in police funding since 2019.

There is a growing body of academic research suggesting more cops on the streets leads to less crime. And again, perhaps this accounts for at least some of the increase in murders, as covid and retirements took more cops off the streets. But we’re still left with the fact that other types of crime went down in 2020 and 2021.

It’s also worth noting that most of the more cops, less crime research doesn't account for the harm done by over-policing. Also, most of the research also only considers the options of more police or less or no police. For many of the problems we’ve tasked to police, there may be non-policing alternatives that produce better outcomes.

Finally, there's scant evidence that overall spending on policing in and of itself has much effect on crime.

The murder surge was driven by the pandemic

Somewhere between true and difficult to know.

Typically, most categories of crime tend to rise and fall together. During the first two years of the pandemic we saw an unusual decoupling of murder from other types of crimes.

Some have tried to claim that this proves the pandemic is unrelated to the murder rate, because generally we see the reverse during times of economic hardship — property crimes go up, while violent crime remains largely unaffected.

But the pandemic didn't just crash the economy. It uprooted every facet of American life. It took more police officers off the street as they got sick or died from covid. It disrupted illicit drug markets, which tends to spur turf wars and gang violence. At the same time, lockdowns and general fear of catching the virus during surges winnowed the streets of potential witnesses, a big deterrent to crime.

Sociologist Randolph Roth has pointed out that over the course of U.S. history, the other times during which we’ve seen a decoupling of murder from property crime were periods of domestic strife, social upheaval, political discord, and when there's greater mistrust of government, particularly among marginalized groups. The pandemic provided all of those things in spades.

The pandemic would also explain why, though in the aggregate we saw a surge in murders across the country, we saw all sorts of weird and disparate trends at the local level. Some cities saw surges in car thefts and break-ins. Some cities bucked the rise in homicides entirely. Some saw homicides stay flat while property crimes soared. This makes sense if we remember that the pandemic hit different cities at different times, and that cities and states responded with widely varying policies. In some places, it seems at least possible that lockdown policies contributed to increases in some types of crimes. But early in the pandemic many of us stayed home regardless of whether or not we were required to. That almost certainly affected crime as well.

The pandemic also resulted in cuts in funding for social services, mental health care, and violence interruption programs, which have shown promise in cutting murder rates in the neighborhoods they’ve been tried.

Murders rose aberrantly, abruptly, and by the most significant margin we’ve seen in decades, and this occurred at precisely the same time we faced a once in a lifetime pandemic. It seems unlikely that those two things aren't related. But even in the areas of social science that provide good, reliable data, academic research often fails to find consensus cause-and-effect relationships. When it does it can take decades. And in criminal justice, the data tends to be incomplete, of questionable origin, and generally unreliable.

The murder surge was driven by the George Floyd protests

Possibly, but it’s difficult to say for certain.

Many cities had already begun to see an increase in murders well before the protests began, though in most places that increase grew more intense after the protests. It seems likely the protests had some effect. Perhaps the early pandemic spawned a slight increase that was then exacerbated by the protests. Or perhaps the pandemic's effects worsened as the year dragged on and the weather got warmer. Perhaps it was a mix of both.

Proponents of this explanation cite the “the Ferguson Effect,” or the argument that police officers tend to stop proactively policing in the face of criticism. It's a controversial claim, and it's possible to find evidence that both supports and contradicts it. This theory also rests on the assumption that when cops do stop policing proactively, crime goes up. That hasn’t always been the case.

The argument here is that if the protests against police brutality did indeed cause police to stop doing their jobs, and this then led to a surge in murders, then the protests are to blame for those additional murders. But you could also argue that if large numbers of police officers refused to do their jobs in response to protests against brutality — knowing that doing so will lead to more murders — that really only confirms some of the protesters' worst criticisms of the police.

Moreover, if proactive policing is effective at preventing crime, we should have seen an increase in crime across the board in the months following the protests, not just homicides. Again, that isn’t what happened in 2020 and 2021, at least in the aggregate. One possible explanation for this is that people were more likely to be at home, so there was less opportunity for burglaries, break-ins, and theft. Still, that should have leveled off as the pandemic wore on. It didn’t.

There's also an “alternate” Ferguson Effect, which posits that high-profile police killings like that of George Floyd undermine respect for police, particularly in minority communities, which leads to less cooperation and less trust, which causes a surge in crime. There’s some evidence for this theory as well. Researchers have found that 911 calls to police — overall but particularly in black communities — are less frequent after high-profile incidents of police violence, including after the George Floyd protests. One recent study compared 911 calls to recorded gunshots, and found a significant decrease in the number of calls to police to report a fired gun shortly after the protests.

To confuse matters more, because both versions of the Ferguson Effect would occur after a highly-publicized protest, it’s difficult to distinguish whether one or both factors contributed to a post-protest increase in crime.

Those who link the increase in homicides to the protests often point out that we didn’t see a corresponding rise in homicides in other western countries after the pandemic. That’s true, but the U.S. is also unique among western countries in its gun availability, stringent drug prohibition, and high base rate for violent crime. That those factors would lead to a very different outcomes in the face of such a massively disruptive event like the pandemic shouldn’t be surprising.

Finally, it’s worth stating here that even if there were some causal link between the George Floyd protests and homicide, it’s unclear what the solution ought to be. The message to black people here seems to be that they have to chose between accepting racially discriminatory policing and police brutality or face diminished policing that will result in more crime and more murders. That isn’t an acceptable set of options.

The surge in murders was fueled by bail reform

False. There is a common misconception that bail reform means releasing dangerous people accused of violent crimes who would not have been released prior to reform. For the most part, that just isn't true. If a judge believes a suspect is truly a threat to the community, that suspect typically won't get bail at all. The purpose of bail is to prevent the suspect from fleeing the area before trial. The main determinant of whether someone gets out on bail, then, isn't how dangerous they are, it's whether they can afford to pay. That means even if suspects are acquitted or their charges are dropped, by the time they get out they may have lost a job, been evicted, or lost custody of their children.

Despite the claims of some police officials and conservative politicians, studies in New York City found bail reform had no effect on violent crime. Even the New York Post, hardly a bastion of bleeding heart reform, found no evidence to support the claim. Another study of four states and nine cities by the left-leaning Prison Policy Center also found no connection between bail reform and violent crime, as did a separate study of Cook County, Illinois, and another pre-pandemic study in New Mexico.

The murder rate was fueled by a surge in gun sales

Possible, but not certain. There was an undeniable surge in gun sales in 2020, at the same time the murder rate shot up. ATF data also suggests that newly purchased guns were more likely to be used in murders in 2020. Moreover, 77 percent of murders in 2020 were committed with guns, up from 73 percent in 2019.

But there's also no evidence that gun sales increased more in places that also saw a bigger surge in murders. And some of the cities that saw drops in their gun murder rate in 2020 have comparatively lax gun control laws, including El Paso, Anchorage, Salt Lake City, and Oklahoma City.

As analysts Jeff Asher and Rob Arthur write, the data is highly suggestive of a link, but still too incomplete to confirm (in part because until recently Congress limited federal agencies' ability to do the research). Of course, it could be that there was a surge in gun sales because of the surge in murders -- people in places where murders went up went out and bought guns to protect themselves.

Whether you think the suggestive data demands more gun restrictions likely depends on whether you believe there's a constitutional right to gun ownership. Whether such laws would reduce the number of murders also depends on the law, how it's applied, and where it's applied. The vast majority of gun murders are committed with handguns, for example, which means more popular gun control measures like bans on what are commonly called assault rifles wouldn't have had much effect.

There’s also little evidence that on-the-ground gun enforcement, like stop and frisk, has any effect on crime, and there’s ample evidence that such laws are disproportionately and discriminatorily enforced against minorities.

So what did cause the rise in murders?

I don’t know, and anyone who says they know for sure is lying to you. We can’t even say for certain what caused crime to drop so dramatically through the late 1990s and early 2000s.

But I would point again to Randolph Roth’s research showing that we tend to see homicides decouple from other crimes in times of great political division, mistrust of government and institutions, and in periods in which minority groups feel particularly marginalized. We’ve had all of that in ample supply over the last few years. Similarly, the political scientist James L. Payne has argued that people tend to kill one another more frequently in societies where there’s more exposure to death, particularly unexpected death. We’ve certainly seen a lot more of that in the last few years, too.

There are other indications that the country is currently in a state of despair, plagued by anger, short tempters, stress, and general despondence. Over the last two years, we've seen aberrant surges in highway fatalities, drug overdoses, anxiety and depression, domestic violence, and alcohol consumption. There aren’t nearly enough therapists and mental health professionals to meet demand. Even our average blood pressure is higher. Also, aggravated assaults were one of the few other classes of crime to go up in 2020. That’s the sort of crime you tend to see when people are angry.

These aren’t problems solved by cable news soundbites and easy, tough-on-crime policies.

Shoplifting/retail theft is rampant right now

Somewhere between false and unknown. This Atlantic piece lays out the situation persuasively, and in great detail. It isn't at all clear that shoplifting crimes are up, even in California, as is often claimed. The allegation that some retail stores are closing due to shoplifting is also difficult to confirm or refute. In San Francisco, for example, drugstore chains like Walgreens had planned to shut down stores long before the alleged shoplifting wave they’d later blame. As for closing in other cities, well, it’s just difficult to say for sure.

Shoplifting in California surged after a new law made it impossible to prosecute people who steal less than $950 in property

False. It’s true that California recently raised the minimum value of stolen goods to charge a felony to $950. It isn’t at all clear that this led to a surge in shoplifting. Moreover, several states have higher minimums. In Texas it’s $2,500. In Georgia it’s $1,500. In Louisiana it’s $1,000. And in South Carolina it’s $2,000. If you are convicted of stealing less than $950 worth of property in California you can still be charged with misdemeanor shoplifting, punishable by up to 6 months in jail.

Didn’t the FBI say police departments aren’t reporting crime statistics? So how can we reliably measure any of this?

As I’ve already pointed out, criminal justice data is extremely dirty. And it’s true that the FBI recently moved to a different reporting system for its annual crime stats. It’s also true that the new system means more than 40 percent of police departments didn’t report statistics for 2021. This is a huge problem.

That said, the FBI can still extrapolate from the data they do have to come up with general estimates for crime figures nationwide. Moreover, even though large police departments like those in New York and Los Angeles didn’t report all of their data to the FBI, most big city agencies — including the NYPD and the LAPD — do keep monthly statistics and make them publicly available on their websites. So it is still possible to make year-to-year comparisons for cities that post their statistics.

Haven’t some police departments been caught juking their crime stats? How can we believe what they report?

The answers to the first question is yes. The answer to the second question is, well, it’s really all we have. Generally, it’s difficult to juke homicide statistics. But other statistics can be fudged. The best I can say here is barring changes in leadership, police department cultures tend to stay pretty static. So if a department is playing with the numbers one year, they’re probably doing the same thing the next year. So year-to-year comparisons will still at least show trends, even if the numbers themselves aren’t reliable. That probably isn’t a very satisfying response. Welcome to the world of criminal justice!

Don’t most crimes go unreported? Isn’t it possible that the crime stats in places with progressive prosecutors or liberal mayors would be higher if people didn’t think that it’s futile to report crimes that will never be prosecuted?

Most crimes do go unreported. Homicides are the exception, for obvious reasons. So homicide data from year to year are probably pretty reliable.

So if non-homicides are under-reported, isn’t it possible then, that the gap between homicides and other crimes in 2020 and 2021 was exaggerated? Fortunately, we can measure this with that other main source of crime statistics in the U.S., the National Crime Victims Survey. The NCVS is a scientifically sampled phone survey of U. S. residents that asks whether they’ve recently been a victim of crime. It’s a good comparative tool because in theory, it should account for people who may not report crimes to police out of fear, embarrassment, mistrust, or whatever other reason.

Over the years, the NCVS has consistently shown that the FBI undercounts crime in the U.S. But if people were even more less likely to report crime during the pandemic, or due to progressive crime policies or criminal justice reform, the gap should have increased between the two datasets for 2020 and 2021. Instead, the NCVS showed a steep drop in both violent and property crime in 2020 — violent crime fell from 21 victimizations per 1,000 people to 16.4, and property crime dropped from 101.4 to 94.5.

We don’t yet have complete NCVS data for 2021, but estimates indicate we’ll see a very small increase in violent crime (from 16.5 to 16.5), and another decrease in property crime.

In other words, the NCVS data severely undermine the argument that U.S. residents have been even less likely to report crime in recent years.

What’s this business about New York being safer than Oklahoma? Is that really true?

It is. By any way you want to measure it. We can look at statewide crime rates:

It’s also true if you just want to compare New York City to Oklahoma City:

Tulsa, Oklahoma’s second largest city, also has a higher crime rate than New York City, and also has a Republican mayor and a law-and-order DA.

It’s also true if you compare towns and cities by their degree of urbanization:

The point here is not to pick on Oklahoma. New York’s murder rate, in fact, has been lower than the overall U.S. murder rate since 2010, a remarkable statistic for a city of that large. In fact, you’re safer in New York City than in just about any other part of the country. (The graph below includes accidents and illness as well, but the point still holds.)

Again, homicides in New York City are down so far this year, but most other types of crime are up, a reversal of the last two years — and a trend that mirrors the rest of the country. But the uptick in other crimes also comes after the election of an ex-cop mayor who ran on a law-and-order platform. I doubt either mayor’s policies did much to affect the city’s crime rate. But if you’re going to blame the previous mayor for the increase in homicides, or credit the current mayor for this year’s decline, you have to explain why other most crimes went down under the previous mayor, and have gone up under this one.

The point is that our perceptions of crime tend to be set by coverage of crime instead of relative risk, and Republicans have successfully spread the unsupportable claim that progressive crime policy causes crime.

Polls have consistently shown that a majority of the public thinks crime is getting worse, even when it isn’t, and the same polls show a big gap between people who think crime is up nationally (most do) and people who say crime is getting worse in their own neighborhoods (usually, most don’t). That gap reached an all-time high in 2020, though it narrowed last year.

The political right is well aware of all of this, so they’re trying to scare the hell out of you. They’re putting out propaganda about criminal justice reform and red vs. blue cities and states that’s just flat out wrong.

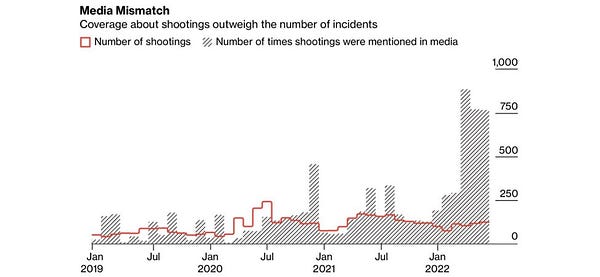

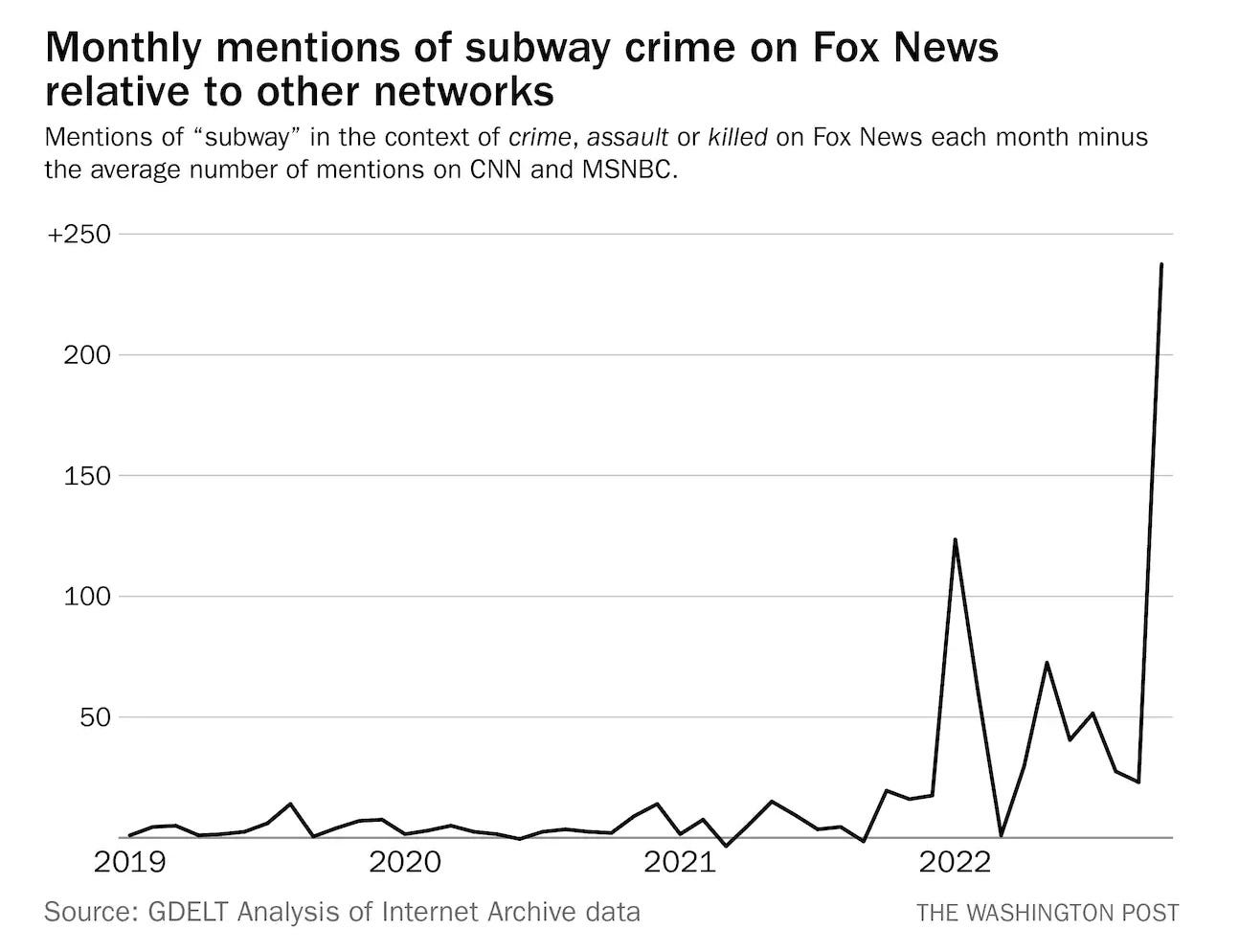

For example, compare this graph of subway crime in New York City (via Gernot Wagner on Twitter) . . .

. . . with this graph of Fox News coverage of Subway crimes in New York City (via Phillip Bump of the Washington Post):

It is true that subway murders have increased in recent years. There were 8 murders on the NYC subway last year. That’s a significant increase over recent years in which there have been 5, or 1, or even none. But that’s 8 murders out of 700 million rides. You’re far less likely to be murdered by simply standing just about anywhere in Oklahoma (or for that matter, just about anywhere in New York) than you are riding the NYC subway. But there’s something uniquely scary about subway crimes, particularly among people who don’t regularly ride subways. So they’re easy to exploit.

The problem of course is that it’s far easier to push these false narratives than it is to debunk them. So the demagoguery works. Voters have consistently ranked crime among their top five issues for these midterms, and Republicans have a 15-20 point advantage over Democrats on the issue. This despite that (1) there’s no evidence that progressive or reform policies cause more crime, (2) there’s little difference between the two parties on these issues in terms of federal policy, and (3) there’s very little the federal government can do about crime, anyway.

I’ve been asked on a few occasions what Democrats should have done in response. I don’t know that I have an answer. If you push back on these narratives you look defensive and draw more attention to the issue. If you change the subject you look like you’re ignoring the issue. And if you embrace the Republican narrative, you cede the debate (as Kathy Hochul is quickly learning in New York).

I’d like to tell Democrats that they should embrace reform not because it’s politically popular but because morally and policy-wise it’s the right thing to do. Republicans are going to demagogue and paint Democrats as soft on crime no matter what they do. See, for example, how Congressional Democrats and the White House are still accused of “defunding” the police, despite enacting significant increases in federal funding for law enforcement. But that advice isn’t particularly helpful to a politician who embraces reform and then loses because of it.

As I’ve previously written, I’ve long worried what would happen to criminal justice reform once crime went up again — as it was always going to do. It couldn’t keep dropping forever. Would we repeat the mistakes of the 1980s and 1990s, and pass draconian tough-on-crime bills that destroy communities but provide no clear benefit to public safety?

At the moment it looks like we will.

Thank you for this!

I know you have a lot going on but do you know anything about non-citizen crime numbers? The CBP website posted a table last month that shows huge increases in non-citizen crime in 2021 and this year. Their numbers seem sus to me but I'm always biased toward skepticism when it comes to agencies who can get more funding when criminal activity seems worse that it actually is and when they are the ones "tracking" crime numbers.

Can you refer us to anyone who is on top of this issue?

In the paragraph on subway crime in New York, shouldn’t the phrase “You’re far less likely to be murdered…in Oklahoma” be “You’re far more likely to be murdered…in Oklahoma”?