The states of indigent defense: part one

A review of the public defense systems in Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, and California

This is the first part of a state-by-state review of indigent defense systems around the country. You can check here for the post that introduced series, but to sum up, last month RAND published a paper with new guidelines on the maximum number of cases attorneys can handle each year while still providing an ethical and robust defense. These new recommendations are an update of the vaguer recommendations put out by the American Bar Association back in the early 1970s, and factor in modern notions of what goes into an effective defense, as well as adaptations to new challenges, like DNA, hiring forensic analysts, and sorting through digital data. That got me thinking about how regularly we see stories, studies, and surveys about overwhelmed, under-funded public defender systems that don’t come anywhere close to meeting even the 1973 standards. So I wanted to see just how pervasive the problem really is.

I had initially planned to put up five posts with 10 state reviews in each. But I received such an overwhelming response and have collected so much information that I’ve decided to break it up into 10 posts with five states each instead.

The narrative for each state draws upon interviews with criminal defense attorneys (public and private), judges, former prosecutors, and others with experience and expertise about each state.

I also tried to find some consistent data for each state for the purpose of comparison. Here’s the hard data I opted to use, along with some context for each figure.

Per capita public defense spending: This is the amount each state spends per capita on public defense.

State spending on public defense vs. prosecutions: I then looked through state and county budgets to find how much public money is spent on prosecutors.

Ratio of public defense spending vs. spending on law enforcement and corrections: I then compared those figures to data compiled by MoneyGeek.com on each state’s spending on law enforcement and corrections. The point here is not that these figures should be equal. It’s more just a way of comparing the way the states prioritize each area.

A caveat on these figures: The first two numbers are often difficult to suss out. A state might fund prosecutors or public defenders at the state level, one or both at the county level, or a little bit of both. Budgeting for the two offices also doesn't always line up. In some states, for example, public defenders also handle child protection, civil commitment, or family law cases that aren’t enforced by criminal prosecutors, but by a separate executive agency with its own budget. In states with a state-run system, those systems also tend not to fund municipal courts.

In some states, the public defense budget includes money for investigators or experts, while in others that money comes from the courts’ budgets. Some states also provide facilities and office supplies for prosecutors that aren’t included in the official budget, while public defenders have to arrange for office space on their own, or out of their own budgets. In others, one or both comes from the counties, and may or many not be factored into the recorded budget. Of course, it’s also worth remembering prosecutors can typically tap the vast resources of police departments and state and police crime labs, which usually have their own separate, much larger budgets. Public defenders typically either hire or contract with those positions out of their own budgets.

So these figures are approximations. But I do think they’re useful for comparing the states.

I also tried to figure out how each state handles the death penalty for those that still use it, along with how states deal with indigent appeals and post conviction defense.

Finally, I looked at fines, fees, and reimbursement. This last category stems from something I saw several years ago while court watching in Louisiana. After a defendant pleaded guilty to a drug charge as part of a plea bargain, the judge began to rattle off the long list of conditions, fines, and fees the man would have to satisfy as part of his sentence. After the judge finished, I was stunned to hear his public defender remind the judge that he had forgotten to also tack on one additional fee — to reimburse e the public defender’s office. I later learned that some of these offices are dependent on such fees to continue operating.

There is of course the obvious point here — indigent defendants are indigent. By definition, they can’t afford representation, so it’s cruel to require them to reimburse the state for legal services. It’s also counterproductive if the goal here is rehabilitation and successful reentry. But the thing that struck me struck most is how perverse it is to put a public defender in the position of asking a court to add to the burden his indigent client will have to meet to be clear of his charges — to make a public defender’s livelihood contingent on saddling his poor clients with additional debt.

Research has also shown that the money states and counties ultimately spend administering and trying to collect these fees far exceeds the revenue they generate. So it’s purely punitive. My primary source for this information was this terrific and thorough report from the National Legal Aid & Defender Association.

I’d like to thank the following folks and groups for their insights, research, expertise, and other assistance: Arnold Ventures, the Sixth Amendment Center, Erin Atkins, Eve Brensike Primus, the Indigent Defense Improvement Division of the California State Public Defender, the Quattrone Center, the National Legal Aid & Defender Association, Pamela Metzger at the SMU Law School’s Deason Criminal Justice Reform Center, Robin Maher, Jessica Brand. Thanks also to my intern Peter Beck for help with research.

If you really want to geek out on this stuff, I also highly recommend the Public Defenseless podcast, hosted by Hunter Parnell. The show features Parnell conducting substantive, in-depth interviews with public defenders and advocates all over the country. He really digs into the local, regional, and national issues affecting indigent defendants and their lawyers on the ground.

On to the review . . .

Alabama

Per capita spending on indigent defense: $13.47

Ratio of DA budget to public defense budget: 2:1

Ratio of state-level police/corrections spending to state-level indigent defense spending: 35:1

Alabama doesn’t provide a whole lot of public information about its public defense system, which makes it difficult to assess. And of course this lack of transparency is itself a problem.

About half the funding for indigent defense comes from the legislature. The other approximate half comes out of a fund populated by fines, forfeitures, and filing fees in civil cases. In 2011, Alabama created the Office of Indigent Defense Services (OIDS) to oversee how each judicial district provides public defense. Technically, each judicial district in the state has a committee that decides the manner in which indigent defense will be delivered — whether through a dedicated office, contracts, or appointments — though OIDS still wields a lot of influence in these decisions.

Several dedicated public defender officers now dot the more urban areas of the state — Montgomery, Birmingham, and Mobile — and public defense in these areas tends to be quite a bit better in those areas. The attorneys with whom I spoke were quick to praise the Birmingham/Jefferson County office in particular. They say it’s well-staffed, well-managed, and approaches the top tier of the holistic model offices. The staff includes social workers, investigators, and experts to help clients with housing, drug treatment, and mental health treatment. An attorney in that office told me they strive to keep caseloads below 150 (felonies and misdemeanors combined). That’s still well above the RAND study recommendations, and roughly on par with the 1973 ABA guidelines. The attorney did tell me that one ongoing problem they face in the office is the low pay the state provides expert witnesses, which can make it difficult to bring them in to testify.

Unfortunately, in 59 of the 67 Alabama counties poor defendants are still represented by either court-appointed private attorneys or flat-fee contracts. Under state law, in counties in which a judge appoints cases to private attorneys, the private lawyers get $70 per hour, well below the $200 or so private attorneys typically charge in the private sector. The court-appointed method has long been plagued by allegations of corruption, such as judges appointing cases to friends and campaign donors, regardless of their experience or qualifications. The state also doesn’t appear to manage the caseloads of appointed or contracted attorneys, so there’s no way to tell if they’re taking on more cases than an attorney should.

Starting about 10 years ago, many counties began switching from court-appointed to flat fee/contract model to save money. But that model has its own problems, because these attorneys get the same fee no matter how many cases they take on, so there’s a strong incentive to bid low and take on more cases than they can handle.

For non-capital cases, there’s also a cap on how much attorneys are paid per case. For serious felonies punishable by between 10 years to life in prison, the cap is $4,000 per case. The RAND study recommends that attorneys spend at least 249 hours on these cases. This means that in Alabama, if you’re a private attorney handling one of these cases properly, your hourly rate comes out to about $16 per hour, roughly equivalent to the average fast food worker wage in New York. For mid-level felonies, the cap is $3,000, which under the RAND study average of 52 hours for such cases, comes to about $52 per hour. For low level felonies, it’s a $2,000 cap, which is about $57 per hour. Perversely, this also means that the more serious the crime and possible punishment, the less the state pays the defendant’s attorney.

“We get $70 per hour until we hit the cap,” says Erin Atkins, who takes appointed indigent cases in Huntsville. “That rate hasn’t changed in the last 11-12 years. Not even for cost of living increases.”

Atkins says the pay was low enough that she eventually had to leave private practice for financial reasons. She now works in the federal public defender’s office. She was previously a solo practitioner with one employee and says her overhead was about $10,000 per month. “You can’t sustain that on $70 per hour,” she says. “So you end up taking on more and more cases just to break even. When I stopped, I had about 100 open files, including capital murder cases.”

Atkins says she often bumped up against the cap on her cases. “I had a case with thousands of pages of evidence that required more than 100 hours of work. I ended up getting paid for about half of that. Defense attorneys joke that once you hit the cap, you are now paying the state of Alabama for the privilege of representing someone. But your obligation is to your client, so you continue to work for free. But you can see how that would be an impediment to doing this sort of work over the long term.”

Atkins says younger attorneys crave experience and want to litigate, so they’ll often eagerly take on indigent cases. But as many of them gain experience, they become more attractive to firms and paying clients, can earn more money, and consequently leave indigent defense. So it’s a system that gradually pushes attorneys out as they become increasingly qualified and experienced and thus perpetually leaves the indigent with less experienced attorneys.

There are also issues with the process of compensating private attorneys. A team of auditors at OIDS randomly combs through a percentage of invoices looking for places to cut compensation. Attorneys say this process can be frustratingly arbitrary.

“I once worked on a murder case from 6 am to 1 am,” Atkins says. “The auditors knocked me down because they said there’s no way I could have worked that long. When you have a lot of documents to review and a hearing coming up, you can absolutely work that long. So you have these people who know nothing about your case dictating how much time you should be spending on it.”

But Atkins says the typical rejection tends to be more petty. “They’ll knock you down because you made two phone calls to a client on the same day, or because you billed 30 minutes to draw up a motion that they say should only have taken 15. It’s petty stuff, but at some point you have to wonder, how much is the state paying these auditors to knock $7 off a bill?”

Atkins says it typically takes three months or more to receive pay and reimbursement. That’s a problem for attorneys struggling to keep a practice afloat. But it presents additional problems when trying to hire experts. “First, the pay for experts is low. It basically means you can’t bring in anyone with any sort of niche expertise,” she says.

An attorney can get an exception to the recommended expert rates, but it requires prior approval from both OIDS and a trial judge. The months-long delay in payment can also put off experts. “I had a case on appeal where the trial attorney wanted to bring in cell phone tower experts,” Atkins says. “But the experts they wanted had been hired for another Alabama case months earlier, and the experts still hadn’t been paid. Understandably, they weren’t willing to come to Alabama again to testify. They essentially had to front the money themselves to fly in and testify, and then wait months to be reimbursed.”

The interesting thing is that while nearly everyone with whom I spoke agreed that dedicated public defender offices provide better representation, most of the state has been reluctant make the switch. Whatever the objection may be, it shouldn’t be cost. There doesn’t appear to be much of a correlation at all. Using figures compiled by AL.com in 2018 and comparing them to 2020 Census data, Jefferson County spends about $15.40 per capita on its dedicated office, while Montgomery County spends $22.07 (these figures include the money paid to private attorneys for conflict cases). Etowah County ($18.44) and Lauderdale County ($18.07) contract all cases to private attorneys, and both spend somewhere in between those two figures, while Huntsville’s private system spends less than all of them ($14.18). All in all, AL.com found that four of the seven counties with public defender offices spent less on indigent defense than it would cost to contract those cases out.

Alabama also struggles to provide adequate habeas representation. Most death penalty states now have an office of capital post-conviction to handle death penalty cases. These offices tend to be comparatively well-funded, and staffed with attorneys with ample experience in capital cases. Alabama does not have such an office. Instead, it contracts most death penalty cases out to private attorneys.

Post-conviction is the stage in which a prisoner can challenge the trial attorney’s performance. It’s also when they can look for and examine evidence that wasn’t in the trial record. It requires dedicated investigators and review from experts. It’s time-consuming, painstaking work, but it’s also when attorneys tend to find evidence of systemic problems — and evidence of innocence. Alabama does not provide counsel for these cases, even in death penalty cases, until a prisoner has already filed a habeas petition pro se, and then only upon a judge’s recommendation. The problem with that is that once you’ve filed a habeas petition, both state and federal courts make it extremely difficult file another one. And if you’ve failed to negotiate the complex procedural rules for filing, the courts will dismiss the petition before even considering it on the merits. That in turn can kill your chances of being heard in federal court.

So at best Alabama prisoners don’t get professional legal help until they’ve reached a stage where such help may already be futile. In 2001, the Equal Justice Initiative sued in federal court to force the state to provide adequate post-conviction indigent defense, at least for capital cases. The Eleventh Circuit acknowledged that the state’s post-conviction representation was inadequate, but ruled that it was bound by U.S. Supreme Court precedent, which states that “there is no federal constitutional right to post-conviction counsel.”

You need only look at a case like Toforest Johnson’s — in which, in addition to about a dozen other injustices, prosecutors and a judge failed to disclose that the state’s only witness was paid for her testimony — to understand why it’s it’s a mistake to trust Alabama’s courts to protect the rights of death penalty defendants.

Alabama also caps the pay of attorneys who take these cases at $7,500 (until 2018, it was just $1,500). It often means this important work often goes to lawyers willing to work for less, which tends to mean lawyers with less experience. The Alabama Post-Conviction Relief Project, a donor-funded nonprofit that provides habeas representation for death row prisoners, estimates that, on average, their expenses come to about $15,000 for a single evidentiary hearing. So each hearing costs about double the maximum the state will pay to represent someone for the entirety of the habeas process.

It’s worth noting here that Alabama sentences people to death at a higher rate than any other state. And since 1976, nine people on the state’s death row have been exonerated. That’s one exoneration for every eight executions.

Fines, fees, and reimbursement:

Alabama does not have a state-administered administration fee to obtain a public defender, but courts can order indigent defendants to reimburse the state for a portion of their legal representation, ranging from $250 for a misdemeanor up to $1,000 for a Class A felony. The state’s courts also have the discretion to order defendants to pay more, and can make full repayment a condition of parole. These fees do comprise part of the funding for public defense in the state.

Alaska

Approximate per capita spending on indigent defense: $86.30

Ratio of DA budget to public defense budget: 1.5:1

Ratio of state-level police spending to state-level indigent defense spending: 91:1

Alaska funds most indigent defense at the state level through two agencies. The Public Defender Agency administers the first line defense, and the Office of Public Advocacy assigns cases that present conflicts with the first office. Most of the state is served by either a public defender office staffed with full and part-time time attorneys or through contracts with private attorneys. Public defense advocates say that in terms of state-level organization and structure, it’s a pretty good model. But the devil is often in the details.

For starters, neither of these offices covers the state’s municipal courts, which handle a variety of charges that can still result in incarceration. Municipal indigent defense is left to local cities and towns, most of which contract to private attorneys or private firms with no state oversight. According to a forthcoming paper by Eve Brensike Primus of the University of Michigan School of Law, Anchorage’s municipal court alone churns out about 20 percent of the state’s indigent cases.

Alaska does spend more per capita on public defense than any other state, and by a pretty wide margin (the next closest state is Wyoming, at $49.98). But this is mostly attributable to the sheer vastness of the state and its high cost of living. Large swaths of Alaska are only reachable by plane or boat. Traveling to those areas is expensive and time consuming, both for attorneys and for any investigators and experts they might hire. (Prosecutors of course can rely on local police, although there’s a shortage of those in the state, too.) And despite its considerable spending on public defense, Alaska still spends 1.5 times more per capita on prosecutors’ offices.

The state’s size also creates logistical problems when it comes to getting mental health or substance abuse treatment for a client, especially when the latter is a condition of probation. A four-hour drive or a flight to one of the state’s relatively few treatment facilities can quickly get expensive.

Alaska struggles to fill public defender positions. One big reason for this is that there’s no certified law school in the state. This means the public defender’s (and prosecutor’s) office has to recruit from law schools in the continental U.S. And while some grads from the lower 48 states may be up for a one- or two-year stint in the state, it’s difficult to recruit attorneys interested in living in Alaska over the long haul, particularly in rural areas. So the state’s indigent defense system can’t build up the sort of experience it needs to function effectively.

Alaska’s most recent indigent defense crisis began in the mid 2010s, when Trumpism overtook the state’s dominant, libertarian-leaning Republican Party, and began rolling back the state’s progress on criminal justice reform. The state began budgeting money to hire more police and prosecutors, but not to hire more public defenders. That led to more arrests and criminal charges, but fewer criminal defense attorneys to handle those cases. Caseloads began to climb. One 2016 study found public defenders in the state handled about 250 cases per year, a figure that was only projected to rise.

On an episode the Public Defenseless podcast, Fairbanks public defender Justin Racette pointed to another problem created by the state’s anti-reform backlash: When the state was considering policies like reducing sentences and bail reform, it created an extensive surveillance system to track the prisoners newly released under anticipated reforms to parole, probation, and bail. But the proposed reforms were never enacted, leaving the state with a huge pre-trial surveillance system, but none of the decarceration reforms that were supposed to come with it.

By 2018, Alaska’s state public defender told the state legislature that the average public defender in the state had twice the number of cases recommended by the ABA. That average defender would need to put in 92-hour workweeks just to meet his or her ethical obligations. Many attorneys burned out and began leaving the job, which only added to the workload of those who remained. This cycle only accelerated after Mike Dunleavy was elected governor in 2018 on a MAGA/law and order platform (“Make Alaska Safe Again”).

In 2019, a state judge addressed the problem in a scathing opinion granting a delay in a murder trial after the defendant’s attorney resigned. The lawyer had been handling over 200 felony cases at the time and resigned due to exhaustion.

The judge wrote, “The record in this case should reflect that, as a result of the policy and budget choices made by the legislative and executive branches the people of Alaska must tolerate long delays in the prosecution of the type of crimes charged in this case - crimes against women, crimes fueled by substance abuse, crimes against law enforcement officers, crimes against rural Alaskans.”

That opinion was well-publicized in state media, and spurred some public discussion about funding. Yet Dunleavy went on to cut another $400,000 from the public defense budget that year, and another $180,000 from its travel budget. One former public defender told a local TV station that due to a lack of indigent defense, some rural mutual aid groups had resorted to teaching Alaskans how to file their own documents in criminal cases.

In 2019, after a series of media reports about overworked public defense attorneys, Dunleavy's administration issued its own report that blew off most of the criticism, and faulted poor management of the public defender offices for the crisis. The governor’s report found that the typical public defender in the state had a weighted annual caseload of about 150. The administration deemed this acceptable, citing the 1973 ABA recommendations.

Public defenders disputed those figures, and 150 is still well above the recommendations in the RAND study. But it’s worth noting again here that 150 cases in a state like Alaska is quite a bit different than 150 cases in, say, Connecticut. One 1999 report specific to the unique challenges of Alaska recommended attorneys in the state have no more than 59 active cases in a 60-hour work week.

Even the governor’s own report found that public defenders spent an average of 13 hours per case. That figure is an aggregate of all types of cases, but it’s still less than the recommended 13.5 hours the RAND study recommends attorneys should spend on the least serious charges like parole and probation violations.

Last February, the ongoing labor shortage sparked a crisis in Nome and Bethel, where the loss of more experienced attorneys left the remaining public defenders in those offices with no choice but to refuse new clients. Bethel had just two full-time attorneys at the time. The head public defender in Bethel wrote, “The agency lacks the capacity internally to provide representation in these matters consistent with its ethical and constitutional obligations.” Nome also had just two attorneys. One had been practicing law for less than a year, and the other was new to criminal law. Neither was qualified to defend high-level felony cases.

After those reports, Dunleavy’s administration finally proposed a 22 percent increase in the public defense budget. That’s a substantial bump, though still only half the 45 percent increase in funding the state earmarked for criminal prosecutions.

Fines, fees, and reimbursement:

Alaska does not charge an up-front fee to obtain a public defender. The state does make indigent defendants reimburse the state for a portion of legal services, ranging from $250 for a misdemeanor trial up to $1,500 for a felony trial, but it does not make repayment a condition of parole. The fees also go to a general fund, not directly to fund public defense.

Arizona

Approximate per capita spending on indigent defense: $21.95

Ratio of DA budget to public defense budget: It’s difficult to come up with a statewide figure. Both positions are funded at the county level, and not all counties make their budgets publicly available. But here are the ratios for a selection of county budgets I could find: Chochise: 3.1:1, Maricopa: 2.3:1, Pinal 1.4:1, Pima: 2.6:1, Coconino: 1.8:1; Mohave: 3.1:1, Gila: 2.3:1, Yavapai: 1.5:1, Yuma: 3.2:1.

Ratio of state-level police spending to state-level indigent defense spending: 30:1

Arizona doesn’t have a statewide public defense system. There’s no consistent state-level funding, and there’s no state agency to provide oversight. It’s all done at the county level. The counties are supposed to get an annual supplement from the state — a percentage of the fines and fees collected for traffic violations and forfeitures. But the legislature can earmark that money, and it often diverts the defense portion to other areas, including to law enforcement. So while indigent defense systems around the state shared $700,000 from the fund this year, they received nothing last year or the year before. Over the same period, prosecutors received $2.6 million from the fund.

Because Arizona counties are left on their own when it comes to oversight and administration of indigent defense, it’s difficult to assess just how many cases public defenders across the state are handling, or if they’re providing adequate representation. We’re mostly in the dark, here.

But a Lee Enterprises report from last January headlined “On the Brink of Crisis” found that public defender offices across Arizona face massive funding and staffing shortages, particularly in rural areas.

We do have some information from a few counties. The Lee Enterprises report found that at least 23 of the 346 private attorneys who took indigent defense cases in Pima County (Tucson) had caseloads well above the 1973 ABA recommendations. One attorney had more than 400. Nearly all of those attorneys also had a private practice, so it’s likely that their total caseloads were even higher (and that their private cases took priority).

The report also found that the budgets for prosecutor’s offices in the state dwarfed those of public defenders, which my own research has also found. Some public defender offices are so constrained that they’re often unable to hire expert witnesses to review the work of state experts. This is particularly true in rural areas, where experts were unwilling to work without added compensation for travel expenses and the time it takes to traverse larger, sparser counties.

Pay rates are also low. Cochise County, on the border, pays a flat fee of $1,000 per felony and $200 per misdemeanor. Maricopa County, the state’s most populous, pays just $77 per hour for major crimes like murder or manslaughter that are contracted out to private attorneys because of a conflict with the public defender office (again, the average range for a criminal defense attorney nationally is about $200/hour, and experienced attorneys can multiples of that). The county pays flat fees for less serious charges, ranging from $1,375 for felonies to $450 per misdemeanor.

Maricopa County does have a dedicated public defender office that represents most indigent clients. The annual reports from that office don’t track caseloads in a systematic way, but the 2014-2015 report does mention the number of cases handled by specialized teams assigned to various courts and programs. According to that report, a 14-attorney team assigned to a regional courthouse handled about 3,000 felonies over the previous fiscal year, or about 215 per attorney. A 10-attorney team specializing in drug cases averaged about 230 cases per attorney. Another team of one full-time and three part-time attorneys handled 864 misdemeanor cases. And a 10-attorney probation team averaged 1,250 cases each. All of these would be well above the 1973 recommendations, and several times more than the RAND recommendations.

There is also a distinct urban-rural divide. Despite the ongoing funding and caseload issues, the sources with whom I spoke have a high opinion of the Maricopa and Pima public defender offices. They say both are well-run and provide high-quality representation, even if both could use more funding and more staff. But it’s quite a bit bleaker in the rural counties.

As for death penalty cases, for decades Arizona provided the absolute minimal representation the courts would allow. Through the 1980s and 1990s, Pima and Maricopa County ranked among the most prolific counties in the country when it came to sending people to death row. At the same time, Arizona’s rate of reversals in death penalty cases was well above the national average. (See Ray Krone for a particularly galling example.)

From the mid-1990s through the early 2010s, state officials periodically entertained advocates who called for reforms like a well-funded state-run capital post-conviction office or adopting the ABA standards for effective death penalty representation. This was mostly because of AEDPA, a federal law passed in 1996 that allowed states to opt-in for expedited federal review of capital cases if they adopted those standards.

But those reforms either fell short of passing or were short-lived. Arizona legislators liked the idea of speedier executions, but weren’t willing to pass the minimum reforms necessary to ensure the people executed received fair trials — or were actually guilty.

The problem with inept capital defense grew particularly urgent in the mid-2000s, when then-Maricopa County DA Andrew Thomas began aggressively seeking the death penalty in about half of first-degree homicide cases. (Thomas would later be disbarred for abuse of power.)

In 2012, Maricopa County finally passed a series of laws requiring defense attorneys in capital cases to meet minimum requirements for expertise, experience, and training. Given Maricopa County sends the most people to death row, the reforms were a significant improvement. “I saw a lot of buck passing early in my career,” says Andrew Sowards, a longtime defense investigator in the state. “You’d have this attitude among some of these attorneys that was like, well, if I miss a few issues in state post-conviction, the federal defenders will catch them. But that isn’t how it works. If you don’t preserve a claim at the state level, it’s dust in federal court. You started to see that change in Maricopa after they stopped letting inexperienced attorneys take these cases.” But the reforms were never adopted statewide.

In most states, post-convictions petitions — a prisoner’s request to be heard on claims after exhausting appeals — are considered civil matters, even though they obviously deal with criminal cases. In Arizona, post-conviction is considered a continuation of the criminal case. Consequently, it’s one of the few states that provides indigent defense for post-conviction habeas claims. Unfortunately, the defense it has provided has not been very good. This is probably why three of the Supreme Court cases that lay out the law for federal review of ineffective post-conviction representation all came from Arizona: The court created a way for people with bad attorneys during post-conviction to get into federal court in 2011, but then essentially wiped out that ruling with the infamous “innocence isn’t enough” case in 2022.

Post-conviction public defense at this stage is appointed, and the appointments are made by the state supreme court. The court has not adopted any minimum standards to insure that those attorneys are qualified and experienced. Moreover, once appointed, those attorneys are then reliant on the county’s from which the cases originated when it comes to getting funding to hire experts, investigators, and other specialists. Just to reiterate, post-conviction is typically the phase in which a prisoner discovers prosecutor misconduct, mistakes and oversight by defense counsel, and evidence of innocence. Arizona has executed 40 people since 1976. In that time, 12 people condemned to death have been exonerated.

Things at the trial and appellate level have improved — at least in the state’s most populous county — to the point that, going forward, indigent defendants are likely to receive good representation. But there’s been little effort to ensure that the attorneys who review cases from the days of Maricopa’s days of aggressive, death-eager prosecutors are adequately funded and qualified.

Fines, fees, and reimbursement:

Arizona charges an up-front administrative fee of up to $25 to obtain a public defender. The state’s courts also have the discretion to make defendants reimburse the state for public defender services, commensurate with “the financial resources of the defendant and the nature of the burden that the payment will impose.” State law also allows full repayment of those fees to be a condition of parole.

Arkansas

Approximate per capita spending on indigent defense: $12.93

Ratio of DA budget to public defense budget: 4:1

Ratio of state-level police spending to state-level indigent defense spending: 33:1

Until the early 1990s, indigent defense in Arkansas was practically nonexistent. Private attorneys were paid $200 for felony cases and $350 for death penalty cases, all payable only after the case was closed. So the pay was the same whether the case was closed with a plea bargain the day the charges were filed, or after a jury verdict three years later. That provided a strong incentive for attorneys to persuade clients to take plea deals or plead guilty. Total expenses for death penalty cases were capped at $1,000. The state also consistently ranked last or nearly last in per capita spending on public defense — a 1984 DOJ study found that the state spent just 71 cents per resident.

In 1993, the Arkansas Supreme Court ruled that the state was responsible for ensuring that indigent defendants receive constitutional representation. That resulted in the creation of the state’s Public Defender Commission (PDC). Today, indigent defense is funded through the PDC, and it’s administered through regional public defender offices around the state staffed with full- and part-time attorneys.

This was certainly an improvement, but problems persisted. In 2013, the PDC published a report on caseloads and staffing. The study found that in order to comply with the old ABA standards, the state would need to more than double the number of full-time public defenders, from 158 to 361. That didn’t happen.

In 2015, the Arkansas Times reported that some public defenders carried more than 400 felony cases per year. And in rural parts of the state, attorneys might drive two hours or more just to get to court while juggling those caseloads. Some told the Times that because of their workload, they often are only able to meet with clients for the first time just minutes before they’re due in court.

The problem only seems to have gotten worse since then. Little Rock saw a record number of homicides last year, and the pandemic pushed many experienced public defenders into retirement. The state did use some federal COVID funding to hire more prosecutors and public defenders, but a 2021 review by state public defender Gregg Parrish found that the state’s prosecutors make about 70 percent more in aggregate salary than the state’s public defenders.

Because of the pay disparity, Parrish says he often loses experienced public defenders to prosecutor offices because he simply can’t compete. Even when he gets a little more money, as he did with COVID relief, Parrish says he has to prioritize spending on retaining experienced attorneys. Because prosecutor offices can keep experienced lawyers, they could use the funding to create new full-time positions, only worsening the personnel disparity.

There’s also a massive funding disparity across the state. Both prosecutor and public defender offices are with an appropriation from the state legislature. Parrish says that in recent years he’s been able to persuade legislators to mirror any increases in prosecutor budgets with similar increases to defense budgets. The baseline budgets are still lopsided, but the increases have been fairly equitable.

But each county in Arkansas can also supplement the state appropriations, and this is where the disparity goes haywire. Each year, Parrish works with the prosecutors to compile a report on state and county spending on prosecution and defense offices for each county and judicial district. He shared the 2023 figures with me. They’re just astonishing.

Overall, the state and counties combined spend about four times more on prosecutor offices than public defense. In the largest judicial district, which includes Little Rock, it’s about 4.4 to 1.

But some judicial districts are comically one-sided. We can first look at the suburbs of Little Rock:

— The most lopsided district in the state is District 23. That’s Lonoke County, just east of Little Rock. That county spends $484,000 on prosecution and just $15,000 on public defense, or a ratio of 32-1.

— The three counties in Judicial District 20 to the north of Little Rock spend $1.39 million on prosecutions and just $186,000 on public defense — a ratio of more than 7 to 1.

— District 22 is Saline County, to the southwest of Little Rock. The ratio there is also over 7 to 1 — $714,000 vs. $97,000.

Rural parts of the state are particularly bad. In Judicial District 18 West, which includes sparsely populated Montgomery and Polk Counties, prosecutors get $420,000 in public spending, while public defenders get $26,000, a 16-1 disparity. The personnel budget for prosecutors in that district is $221,000. The personnel budget for public defense is just $2,500. Next door in Judicial District 18 East, the disparity is 20-1, or $934,500 vs. $46,600.

In nearly every judicial district and county, there's a disparity of 3:1 or higher, with most somewhere between four to eight to one. The closest any county comes to parity is Washington County (Fayetteville), where prosecutors enjoy a 1.8 to 1 advantage.

Earlier this year, the Arkansas legislature and Gov. Sarah Huckabee Sanders enacted a new law that eliminates parole for some offenses and for others significantly reduces the amount of time prisoners can have shaved from their sentences for good behavior. Longer guaranteed sentences means fewer defendants will be willing to accept plea bargains, which means more trials, which will require significantly more time and manpower from public defenders. One trial can take up 20 or more hours per week of an attorney’s time.

“There’s a real aversion among public defenders toward going to trial,” one former public defender, now a criminal defense attorney in private practice, told me. “Trials eat up a lot of your time. When you’re carrying that many cases, a trial means less time for all of those other cases. So there’s pressure to make your clients take plea offers, even if they say they’re innocent.”

Sanders also put a freeze on state hiring, which has prevented the PDC from filling public defender vacancies across the state. In February, Parrish sent Sanders a letter pleading for an exemption, arguing that the freeze had exacerbated already unmanageable caseloads. He told a local TV station in May, “When you do the math and the numbers, and with the numbers that keep coming in daily, you're always playing catch up. I don't know how we catch up at this point.”

In a court filing last January, the Pulaski County (Little Rock) public defender’s office reported that its felony attorneys were averaging well over 300 cases per year, and may have to stop taking new clients. The office said it had to turn down death penalty cases, apparently because there was only one attorney on staff qualified to handle them.

Last December, the head of that office told the Democrat-Gazette, “We are in dire need . . . because of the excessive caseloads. It’s overwhelming for any attorney. It’s beyond what any lawyer should have to do. Whatever was considered a high caseload before the pandemic, it doesn’t hold a candle to what we’ve got now.”

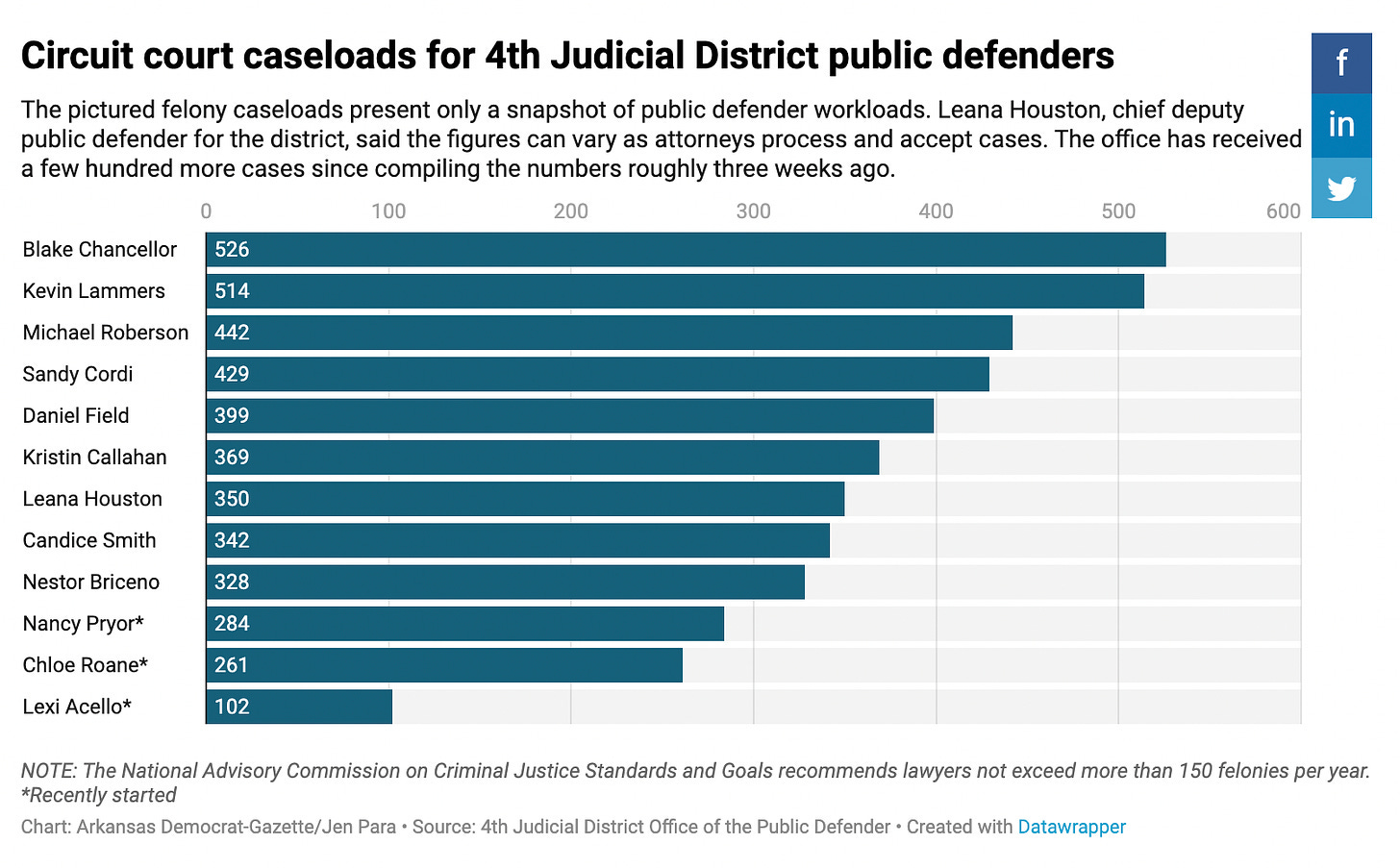

This Democrat-Gazette chart of felony caseloads for public defenders in Little Rock is remarkable. Again, even the 1973 recommendations set the upper limit for annual felony caseloads at 150. These are the current case loads for these attorneys. Over the course of a year, they’re likely quite a bit higher.

Outside of Little Rock, the Arkansas Times recently reported that in Craighead County, one circuit court lacked a public defender for about half the court’s criminal docket, and about 70 defendants facing serious felony charges were unlikely to have counsel by the time of their trials.

Rural parts of the state face additional challenges. Many rural public defenders are only paid for part-time work — about $30,000 per year for 20 hours per week. But they work full-time hours, handling 100-130 cases per year. So many are quitting, and the state has had a hard time attracting applicants for the open positions (though Parrish does tell me that this is starting to improve).

Then there are the “first appearance” problems. As it sounds, a first appearance is the first time someone who has been arrested appears before a judge. It’s at this hearing that the judge rules on whether there was probable cause for the arrest, sets bail, and may hear challenges to the legality of a search. Advocates say it can be a critical time in a case to get arresting officers to commit to a story on the record and to begin to get leads on possible defense witnesses.

In some Arkansas, defendants routinely face first appearances without an attorney. Benton County is currently facing a federal lawsuit over this. The lawsuit was filed in both state and federal court. Oral arguments for the state lawsuit will take place next month. A federal judge recently rejected a motion to dismiss the federal lawsuit.

But people in Arkansas with whom I’ve spoken say it isn’t just Benton County. Aside from Little Rock and Fayetteville, the problem is pervasive across the state.

Some district court judges hold “cattle call” first appearance sessions (in which multiple defendants are addressed at once) at the jails themselves, sometimes at 5:30 or 6 am in the morning. The hearings aren’t always announced ahead of time, and public defenders aren’t told about them. And because district courts aren’t courts of record, there’s no video or audio, and there’s no court reporter. There’s no record of the proceedings at all.

But even if the complainants win that Benton County lawsuit, Parrish says this won’t be an easy problem to solve. “These districts have full-time prosecutors, while most of the public defenders are part-time,” he says. “So even if the public defender gets notice of a hearing — and they usually don’t — it might require an hour-long drive to and from the hearing for part-time work for which they’re getting very little pay.”

In some districts, these district judges travel from county to county, so they may not hold hearings in a particular county for a few days. So if you don’t get appointed an attorney in time, you may have to wait until the next time the judge is in town.

Even when defense attorneys are present for these hearings, they often call in virtually, and have no time to confer with new clients before they appear in front of the judge.

Ideally, an attorney would also get to question the arresting officer about probable cause, or talk to a client’s employer or relatives to argue for lower bail. In reality, even when an attorney is present, these hearings take just a few minutes. “If you dare to question the arresting officer, a three-minute hearing can quickly turn into an hour,” Parrish says. “That’s a good way to get on the wrong side of a judge who you need to be on good terms with for your other cases.”

After a judge sets bail, prosecutors have 60 days to decide whether to bring charges. Only then does the judge appoint a public defender. If it’s a felony charge, the district judge may also kick the case up to the circuit court, which then delays everything further. In the end, a defendant could spend months behind bars before ever seeing an attorney.

The district judges who hold these hearings also don’t seem to be fond of transparency. In July, a former Arkansas judge named Jon Comstock attempted to attend an early-morning hearing held at the Benton county jail on behalf of an advocacy group. He was put in an “observation” room where he could see the hearing, but couldn’t hear it. When he objected, the judge held him on contempt and had him arrested.

In a motion to dismiss the charge, Comstock’s attorney argued that the contempt charge was the result of an attempt “to observe Judge Griffin’s ongoing, probably unconstitutional and definitely rule-violative practice of holding court inside a locked jail in the early morning hours with no prosecutor, no public defender and no record.” Comstock’s case is still pending.

The horrifying death of Larry Price illustrates how easily this system can allow someone to slip through the cracks. Price, who suffered from schizophrenia and a variety of other mental illnesses, was arrested in 2020 after entering a police station and allegedly making threatening comments while forming his fingers into the shape of gun.

It isn’t clear if Price was provided with an attorney for his first court appearance, though my sources in Arkansas say they wouldn’t be surprised if he wasn’t. The judge set bail at $1,000. Price couldn’t pay, so he was jailed in solitary confinement. He did eventually get a public defender, who got a judge to order that he be examined for mental fitness by a company that contracts with the state for such evaluations. But prosecutors then canceled that evaluation, and insisted that it be done at a hospital in Little Rock instead.

Even if everything had gone to plan, the wait for a transfer from rural parts of the state to the Little Rock hospital that performs these evaluations can take months — during which a potentially mentally ill person remains incarcerated and untreated in a county jail.

But Price’s evaluation never happened. Instead, he remained in solitary confinement at the jail for a year. According to a lawsuit filed by his family, Price’s mental illness went untreated for most of that year. He deteriorated quickly, dropping from 185 pounds to just 90. Jail and medical staff documented his worsening psychosis, he refused to eat, and instead ate the styrofoam tray his food was served on and, eventually, his own feces and urine. When he was finally found dead in his cell, he was emaciated and his skin was pruned from being submerged in wastewater and urine. In the 48 hours leading up to his death, as he slowly died of starvation and dehydration, protocol dictated that jail staff check on Price once every 15 minutes — or more than 300 times. The log for each of those checks included the same four words: “Inmate and Cell OK.”

(In a court filing, attorneys for the private medical contractor insist that Price received standard care, was belligerent, and refused his medication. The sheriff’s office says Price had to be treated at the state hospital because it’s the only place that will do such evaluations for people with a history of violence. The sheriff also put Price’s weight at 125 pounds, not 90.)

Sebastian County spends about $1.17 million on prosecutions, and just $265,000 on public defense. The county’s public defense consists of 10 full-time attorney positions (though one “full-time attorney” position will sometimes be filled by two part-time attorneys) and 6 full-time support staff. By contrast, the prosecutor’s office has 16.5 attorney positions and 21.5 support staff positions.

Price’s public defender did file some motions in his case, and I’m not arguing that her representation of him was deficient. It just isn’t clear from publicly available information. But defense attorneys I spoke with in the state also said it’s difficult to give a difficult case like Price’s the attention it deserves if you don’t have a mental health specialist on staff, you’re faced with long drives to courthouses, and you're juggling an excessive caseload.

They also weren’t surprised by what happened to Price, and said that it isn’t uncommon for mentally ill people to be held for months without being charged, nor is it uncommon for them to go months without seeing their attorney. When I asked Parrish about Price, he said, “I wouldn’t say what happened to him happens often, but I also wouldn’t say that I haven’t seen it before.”

As for conviction, its up to the discretion of the head of the PDC — or Parrish — whether to appoint counsel. Under state law, Parrish is only required to appoint indigent counsel for habeas claims in death penalty cases when there’s a claim of ineffective assistance of counsel. For any other claim, and for all non-capital cases, appointing habeas counsel is purely discretionary.

Parrish says he rarely appoints counsel outside of the narrow provision required by state law, and that he’s rarely asked to do so. Pay for habeas work $100-$125 per hour. There’s no cap. Parrish says there are also “probably less than 10” lawyers in the state qualified to take such cases.

Given Arkansas' history of paltry pay for appointed counsel in death penalty and serious felony cases, I asked Parrish if he ever approved habeas representation for prisoners convicted in the 1980s or 1990s who maintain their innocence. He said he never has, but that he’s also never had a request. He also agreed that most Arkansas prisoners likely don’t know they can try. Arkansas also has no real way for people to get back into state court after exhausting their appeals, even with a strong innocence claim. Their best hope is in federal court (and the odds there are pretty bleak). So unless it’s a death penalty case, indigent representation for post-conviction claims just doesn’t exist. (I’ll plug my report on the case of Charlie Vaughn, here, which I think is a pretty potent illustration of how prisoners are left on their own to make these legally complicated claims, then punished when they don’t make them properly.)

The Arkansas system grants a lot of discretion to whoever heads up the PDC. That person distributes funding around the state, lobbies the legislature, appoints counsel in death penalty cases, and approves billing, expenses, and the hiring of experts. Everyone with whom I spoke had high praise for how Parrish has handled those responsibilities, especially given the limited resources. But several also said that they worried about what would happen if the position were given to someone less committed, less qualified, or less competent.

Fines, fees, and reimbursement:

Arkansas charges an up-front fee to obtain a public defender that can range from $10 to $400. The fee is administered by the courts and the amount is based on the expected amount of work required in the case (judges also have the option of waiving the fee). The courts can also make indigent defendants repay the state for a portion of their defense. The fees range $65 for a quickly-dispensed misdemeanor to $12,500 for trial, appeal, and post-conviction in a death penalty case. Repayment of these fees is not a condition of parole under state law. The fees go directly to the state’s fund for public defense.

California

Approximate per capita spending on indigent defense: $33.95

Ratio of DA budget to public defense budget: 1.8:1

Ratio of state-level police/corrections spending to state-level indigent defense spending: 29:1

Despite its progressive reputation — and that it ranks in the top 10 in per capita public defense spending — California has one of the most erratic, least transparent indigent defense systems in the country. Except for the appeals process, which is handled and funded by state courts, everything from funding, to method, to administration of indigent defense is left to the counties. The state plays little role at all. Just this past March, the L.A. Times ran a staff editorial chastising the state for its lack of commitment to indigent defendants.

California is a big, diverse state, and with little state oversight, there’s lot of variance in the quality of public defense. The attorneys and advocates with whom I consulted say some public defender offices — including those in Los Angeles, Alameda (Oakland), San Francisco, and Contra Costa counties — are among the best-run in the country.

But even those offices still have problems with caseloads. In March of last year, over 300 public defenders in Los Angeles signed a public letter stating that they “have reached the point where they can no longer continue to accept new cases while continuing to provide effective representation to our clients.” In Alameda County, public defenders have been conflicting out of cases not because of tangible conflicts, but because their workloads have grown too large to provide effective representation. Those cases are supposed to then go to private attorneys, but there’s also a growing shortage of attorneys willing to take those cases.

“There’s a huge tension in the state,” one reform advocate told me. “The big cities are much more advanced in terms of funding and structure. They have investigators, social workers, and immigration lawyers. But they still have huge caseloads and need more funding. Meanwhile, there are rural areas that have nothing. So do you advocate for more funding for big offices handling thousands of clients that are doing a good job but lack the resources to service them all, or for rural areas where there are far fewer clients and cases, but there’s really no system at all?”

In rural parts of the state, the problem is not just the deficiency of the systems, but very little transparency. Last year, the state’s Legislative Analyst’s Office issued a report which found that “the state currently lacks comprehensive and consistent data that directly measures the effectiveness or quality of indigent defense across the state. This makes it difficult for the Legislature to ensure effective indigent defense is being provided.”

California officials don’t even appear to want to know if indigent defense across the state is adequate.

The report did find that “in 2018‑19, spending on district attorney offices was 82 percent higher than on indigent defense,” and that “over the past decade, spending on district attorney offices has been consistently higher—and growing at a faster rate—than spending on indigent defense.”

Among the other findings:

— Including appeals and habeas, the state spends about twice as much trying to prosecute indigent defendants as it does defending them (not accounting for the cost of arrest and incarceration).

— Among counties that do have public defender offices, those offices on average have about half the number of employees as DA offices, and prosecutors have lower caseloads and far better access to clerical staff and investigators (and this is not considering their access to police department resources).

— Among the counties that did supply information, there was substantial variance in these figures among public defense systems around the state.

I also spoke with Galit Lipa, head of the Indigent Defense Improvement Division (IDID) of the Office of the State Public Defender. The State Public Defender office’s duties are mostly limited to representing indigent defendants on post conviction petitions in death penalty cases, but the IDID does provide some training and assistance to county public defenders who want it. But Lipa’s office also recently commissioned a survey of the current state of indigent defense in California. It hasn’t been published yet, but I was given a preview. A few highlights:

— About 57 percent of California counties fund a dedicated public defender office. About 36 percent contract indigent defense out to private attorneys, and 7 percent assign the work to private attorneys on a case by case basis.

— All but one of the 32 counties that do have a public defender office also have at least one private investigator on staff. Among the counties that contracted work to private attorneys, less than half of those surveyed said the county employs an investigator to assist those attorneys. In those that don’t, the attorneys who take indigent cases must hire an investigator themselves.

— The survey also looks at budgeting for DA’s offices and public defenders. All but one California county budget more money for prosecutors than for public defenders, and for most it isn’t close. In 55 percent of the counties surveyed the public defense budget was less than half the budget of the district attorney. In 13 counties, it was less than 30 percent.

— Indigent defendants in the state are about 20 percent less likely to serve prison time if they’re represented by a dedicated public defender office than if represented by a contract employee. They’re about 40 percent less likely to serve time in jail.

When advocacy groups have attempted to survey the state of public defense in less-covered parts of the state, they’ve found problems nearly everywhere they’ve looked.

— In Del Norte County, all indigent defense is contracted out to private attorneys, with little to no supervision. A report released in May found that attorneys who take felony cases were handling about 200 at the time of the report. Again, that isn’t an annual figure — it was the number of open cases they had at the time.

— A former public defender in Lassen County recently told Lee Enterprises that budgeting for her office was so tight that she didn’t have an office chair — “staff wandered the Lassen County office looking for any broken chairs.”

— When the ACLU sued Fresno County several years ago, the organization found that the public defender office had 60 attorneys to handle over 42,000 cases, a whopping average of 700 cases per attorney. Some had more than 1,000 cases per year. The attorneys who specifically handled felony cases averaged more than 400 per year. Because of the workload, there was a lot of turnover, leaving indigent defendants with inexperienced lawyers who pressured them to plead guilty.

In just the last few years, the ACLU has also found systemic problems with indigent defense systems in Lake County, Santa Cruz County, and Kern County. As the Sixth Amendment Center points out, these are merely four counties that happened to receive some scrutiny. It’s likely that lots of other counties are providing inadequate defense, but it’s hard to gauge just how pervasive the problem is when there’s so little transparency.

In 2020 Gavin Newsom signed a new law that would provide some dedicated indigent defense funding at the state level for appeals and habeas representation. But three years later, Newsom diverted $50 million of that funding to law enforcement to fight retail theft.

Fines, fees, and reimbursement:

It isn’t all bad news. California previously imposed a a $50 up-front administrative fee to obtain a public defender, and also allowed counties to impose their own additional fees. The state also allowed courts to make indigent defendants reimburse the state for a portion of legal services. Both policies were repealed with a sweeping reform bill passed in 2021. California is now one of only a few states that doesn’t burden indigent defendants with any fees or charges for legal services, and it’s the only state in recent years to repeal existing policies.

To close out this first installment, I’ll just add that these are enormously complicated issues that can be difficult to sort out. The nature of this project requires also me to make generalizations. I’m sure there are excellent, diligent, conscientious private attorneys who take indigent cases by way of appointment or contract, for example, just as I’m sure there are inept or inattentive attorneys in dedicated public defender offices.

But generally, the consensus among the many people to whom I’ve spoken is that a dedicated office is preferable to an appointment system or a system that contracts to individual attorneys. (As I pointed out in the introductory post, some of the best public defender systems in the country are actually a hybrid — they’re dedicated nonprofit public defense offices that contract with cities or counties.)

There are also a ton of variables beyond funding, caseloads, and delivery method that might affect the quality of an individual defendant’s representation. I’ve done my best to accurately summarize the current state of these systems based on my research and interviews with policymakers, advocates, and defense attorneys on the ground. But if you have experience in one of these states and think something I’ve written is inaccurate, please let me know. I can’t promise I’ll agree with you — there’s often disagreement between public defenders themselves on some of these issues — but I can promise to hear you out.

For the next post in this series, I’ll look at the indigent defense systems in Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, and Georgia.

If you’re a public defender in one of those states or have other expertise that you’d like to share, I’d love talk to you. Please feel free to reach out over email.

Invaluable reporting as always from Radley Balko.

If public officials were required to use indigent defense, funding would triple overnight.