The retconning of George Floyd, part three: the great flattening

The revisionist campaign to exonerate Derek Chauvin is about one thing: preserving police impunity

(Note: This is part three of a three-part series on the documentary The Fall of Minneapolis and the effort to retroactively justify Derek Chauvin’s murder of George Floyd. You can read part one here, and part two here.)

There’s a flattening that takes place after a high-profile incident of police abuse sparks civil unrest.

There’s the initial media coverage and viral spread on social media. This is followed by outrage, then protests. In some cases, the protests may be accompanied by rioting or looting. Much of that violence is often — but not always — in response to an overly aggressive police response.

Inevitably, all of this is followed by backlash. Police groups and conservative pundits seize on any violent incidents, then start to question the incident that sparked the protests to begin with. Sometimes, new evidence reveals that the precipitating event didn’t happen the way it was originally reported or portrayed on social media. Other times, the evidence confirms the initial account, or shows that the police abuse was even worse than initially thought.

But the pushback from the right tends to happen regardless of what the evidence shows. This then leads to a predictably partisan split in public opinion, not just about the initial incident, but about everything that followed.

The thing is, protests and civil uprisings are rarely just about a single event. Watts didn’t explode in 1965 because black people in Los Angeles were outraged over the arrest of Marquette Frye — an arrest that was largely justified. The riots were the product of years of tension between city police and black residents, as the McCone Commission would later document. Three decades later, the L.A. riots weren’t only about Rodney King. As the Christopher Commission would later find — and as we’d see with the Rampart scandal and the decades long problem of gangs inside the L.A. Sheriff’s Department — they were about systemic brutality and racism from two police departments rife with corruption and abuse.

It’s the same story, over and over with these incidents. Freddie Gray, Tamir Rice, Elijah McClain, LaQuan McDonald, and Breonna Taylor — these killings didn’t spark uprisings just because people were furious about one particular death. They all took place in cities with long, well-documented patterns of police abuse, corruption, and racism.

I often see white people ask why we don’t see mass protest after white people are unjustly killed by police. This is why. Polling after George Floyd’s death found that 70 percent of black respondents had at least one bad experience with police. Nearly half feared for their lives. The corresponding figures for white people were just 23 and 16 percent.

White people look at the killing of, say, Daniel Shaver, Duncan Lemp, or David Hooks and think it’s a terrible thing that happened to someone else. But many black people look at the killing of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, or Elijah McClain and think, “That could have been me” — or a brother, sister, daughter, or son.

One particularly potent example of the flattening we see after civil unrest came after the 2014 protests in Ferguson, Missouri. After the death of Michael Brown, we learned that black and poor residents of St. Louis County were essentially treated like walking ATMs. The mid-20th Century migration of white people to the suburbs, and then the exurbs — and their attempt to exclude black people each step of the way — resulted in an astonishing number of tiny “postage stamp” municipalities, most of which had their own police department and were funded by fines and fees imposed on their residents. The poorer the town, the more it needed fines and fees to operate.

This meant cities like Ferguson relied on predation to stay afloat. They needed people to commit low-level infractions. They then sent the disproportionately white cops from the outer suburbs who comprised their police forces to harass the low-income black people those cops were supposed to be serving. Some officers were explicitly reminded that their paychecks depended on imposing as many fines as possible.

Some of the towns around Ferguson had several times more active arrest warrants for failure to appear in court over minor violations than they had residents. When I went to St. Louis County to do some reporting, I attended municipal court sessions so overcrowded that they had to move them to gymnasiums. The procession of overwhelmingly black defendants moving through these gyms as their cases were adjudicated by white judges and prosecutors felt like a dystopian assembly line.

This longstanding dynamic created an inescapable cycle of poverty and despair, and gave rise to predictable tension and anger between residents and police.

When black people took to the streets of Ferguson in the summer of 2014, this is what they were protesting. In the initial narrative, Officer Darren Wilson had confronted Michael Brown for jaywalking. We now know that poor people in St. Louis County were often targeted for jaywalking, trespassing, and loitering.

St. Louis County was a powder keg, bulging from years of tension, frustration, and resentment. Brown’s killing simply lit the fuse. The overly aggressive police response then poured gas on the resulting fires.

But when conservatives and police advocates talk about Ferguson today, all of this is lost. They focus solely on the death of Michael Brown, and the “hands up, don’t shoot” mantra. It was, they say, all a lie.

They’re of course referring to the evidence showing that Brown’s death didn’t happen the way it was first reported and recounted by protesters. Multiple investigations, including the one conducted by the Department of Justice under Eric Holder, and another by black progressive district attorney Wesley Bell, either found Wilson was justified in shooting Brown, or found insufficient evidence to charge Wilson with a crime.

The truth of what happened between Wilson and Brown needed to be investigated and aired. And if Wilson’s actions were justified, he deserved to be vindicated.

But focusing solely on the precipitating incident collapses what the Ferguson protests were actually about. It erases the fact that the anger behind those protests came from real suffering inflicted on generations of residents. It glosses over the structural racism that trapped disproportionately black families in perpetual poverty.

And perhaps most importantly, it became a way to preemptively discredit the next protest.

This brings us to the focus of this series — the campaign to retroactively exonerate the police for killing George Floyd.

The main reason why Floyd’s death sparked the largest civil rights protests in U.S. history was that video. We all saw with our own eyes the nonchalance with which Derek Chauvin continued to kneel on Floyd’s back as Floyd grew weak, went limp, and lost consciousness. It was as clear and demonstrative evidence of a police officer’s utter disregard for the humanity of a black man as you’ll find. Most of us saw no justification at all for the way Floyd was treated.

The unassailability of that footage is also why so many white people joined the protests. It’s why there were protests in the suburbs, the exurbs, and in small town America. Even my hometown of Greenfield, Indiana — where the Klan was still active while I grew up — had a Black Lives Matter protest.

Something about Chauvin’s callous body language as a man died beneath him lit a fire even in people who rarely experience police profiling, harassment, or brutality. Polls showed an unprecedented percentage of white people acknowledging police racism and abuse, as well as support for reforms that would have been nonstarters prior to Floyd’s death.

This is a big reason why it’s so important for police advocates like the people behind The Fall of Minneapolis to discredit the state’s case against Chauvin. If you can convince white people that it was all based on a lie, they can go back to dismissing black people’s allegations of police abuse. If you can persuade a large enough portion of the population that none of it happened the way we all saw it happen — if you can get them to reject the evidence of their own eyes and ears (to borrow a phrase) — you not only chip away at their support for reform, you make them reluctant to sympathize with the protests yet to come.

A broken department

One of the major themes of The Fall of Minneapolis that I haven’t discussed much here is its effort to build sympathy for the city’s police force. The film goes into great detail about the abuse protesters hurled at law enforcement and the long hours cops put in after Floyd’s death, arguing that the city then further disrespected the police by handicapping them from responding with adequate force while the city burned.

I don’t doubt that there are decent cops at the Minneapolis Police Department who endured verbal abuse in the summer of 2020. But again, the protesters’ anger didn’t come from nowhere. As we saw with Baltimore, Cleveland, Chicago, Ferguson, and other cities, residents of Minneapolis were served by a dysfunctional and abusive police department.

To understand just how dysfunctional and abusive, I recommend reading the report released last year by the U.S. Department of Justice documenting the results of a civil rights investigation into MPD. It’s jaw-dropping.

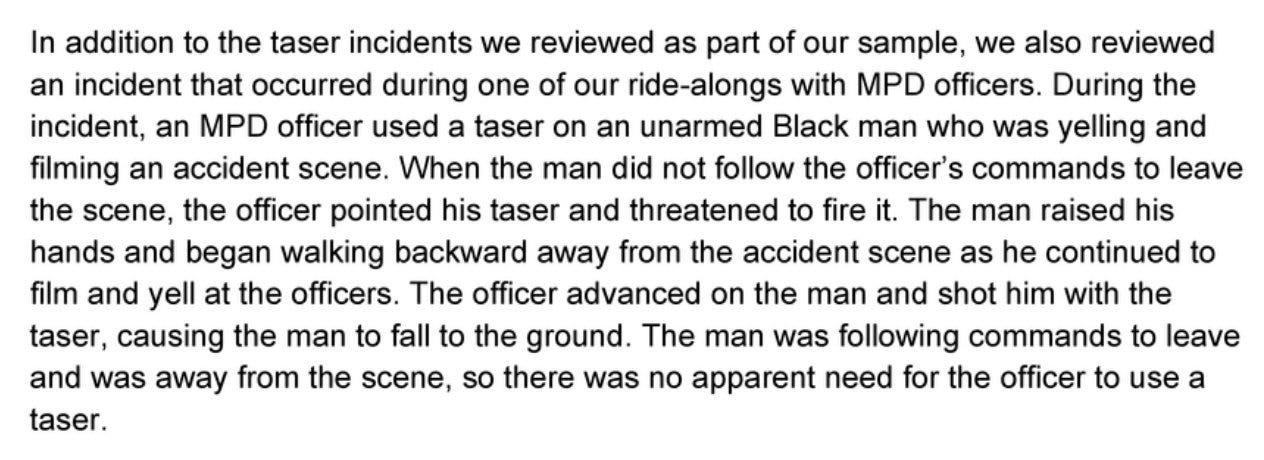

One of the first passages that jumped out at me described an incident in which an MPD officer tased an unarmed, homeless black man who was compliant, walking away, suspected of no crime, and posed no threat.

On the surface, this doesn’t seem much worse than dozens of other incidents documented in the report. But then you see it. The officer did this as a DOJ investigator was in his patrol car for a ride-along. It’s as clear and astonishing a testament to a culture of impunity as you’ll find.

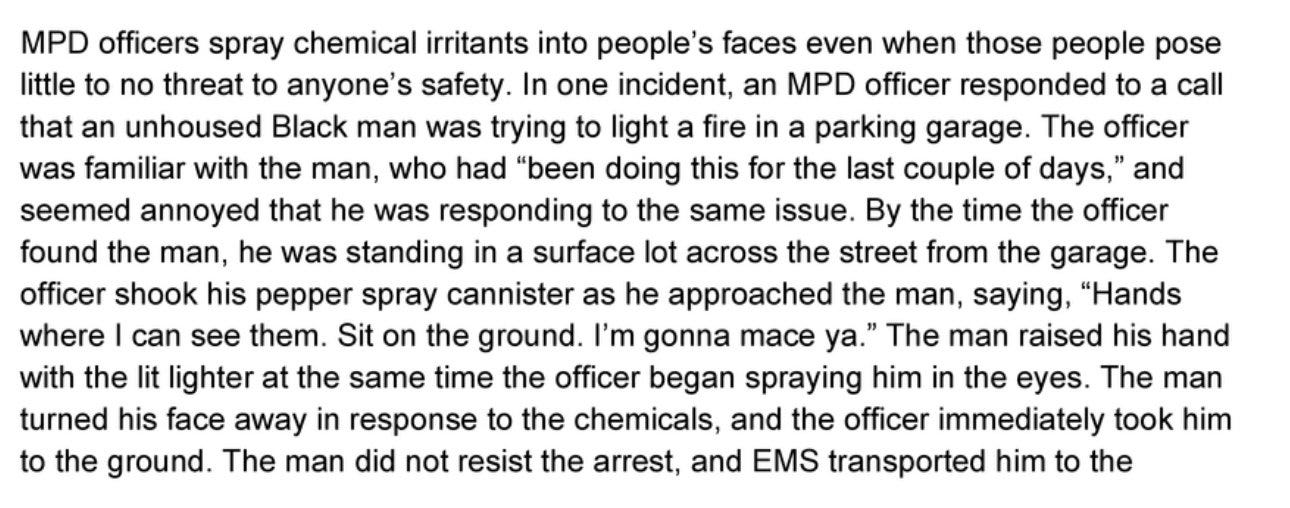

The report documented a relentless litany of abuse. Note that in this next incident, it isn’t even a matter of an officer losing his temper in the heat of the moment. The chilling part is the calculated way he announces his abuse before carrying it out. It’s the sheer mundanity of it.

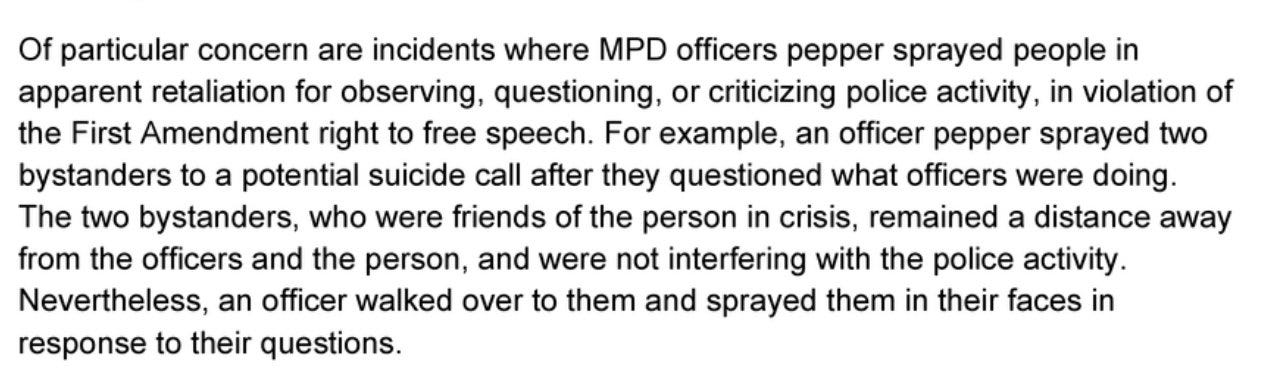

The DOJ report found numerous other incidents in which MPD officers used chemical irritants not as a compliance tool, but as punishment for people they found annoying.

Here’s another incident:

The report also found ample evidence of racism within MPD. Here’s an incident involving some Somali-American teens.

Imagine there was no cell phone video of this incident. Imagine these teens tried to file a formal complaint, or went to the press. How far do you think they’d get? Who would listen to them? Who would have believed them?

During another routine traffic stop, MPD officers yanked a black teenager out of a car, took him to the ground, cuffed him, and threatened to tase him. His crime? He wasn’t wearing a seatbelt.

The report found routine racial profiling at MPD. The city’s officers stopped black motorists and pedestrians over white motorists at a rate of 7 to 1. For Native Americans, it was 8 to 1.

This of course isn’t unique to Minneapolis. A mountain of studies have shown that black people are far disproportionately subjected to traffic stops, including pretext stops (stops based on “suspicious activity” with no actual traffic infraction). Black people are also more likely to be searched, even though most studies show that searches of white motorists are as or more likely to turn up contraband.

MPD was also far more likely to conduct stops for minor traffic violations in black neighborhoods than in white ones. The DOJ report notes that this was true even after accounting for accident rates in those neighborhoods.

A common justification for such discrepancies is often that they’re a tool cops use to prevent more serious crimes. That is, allowing police to make pretext stops of “suspicious” vehicles helps find illegal guns, or dangerous people with outstanding warrants.

The DOJ report found that this just isn’t true.

If just 0.3 percent of pretextual stops are actually producing illegal guns, it means innocent black, Latino, and Native American people are being disproportionately harassed because of suspicions that 99 percent of the time aren’t accurate. And these figures suggest such suspicions are largely driven by motorists’ blackness, Latino-ness, or Native American-ness.

The bias becomes especially apparent when we look at which motorists MPD cops subjected to searches and use of force. Note that these figures are based on motorists who exhibit similar behavior after the stop is initiated.

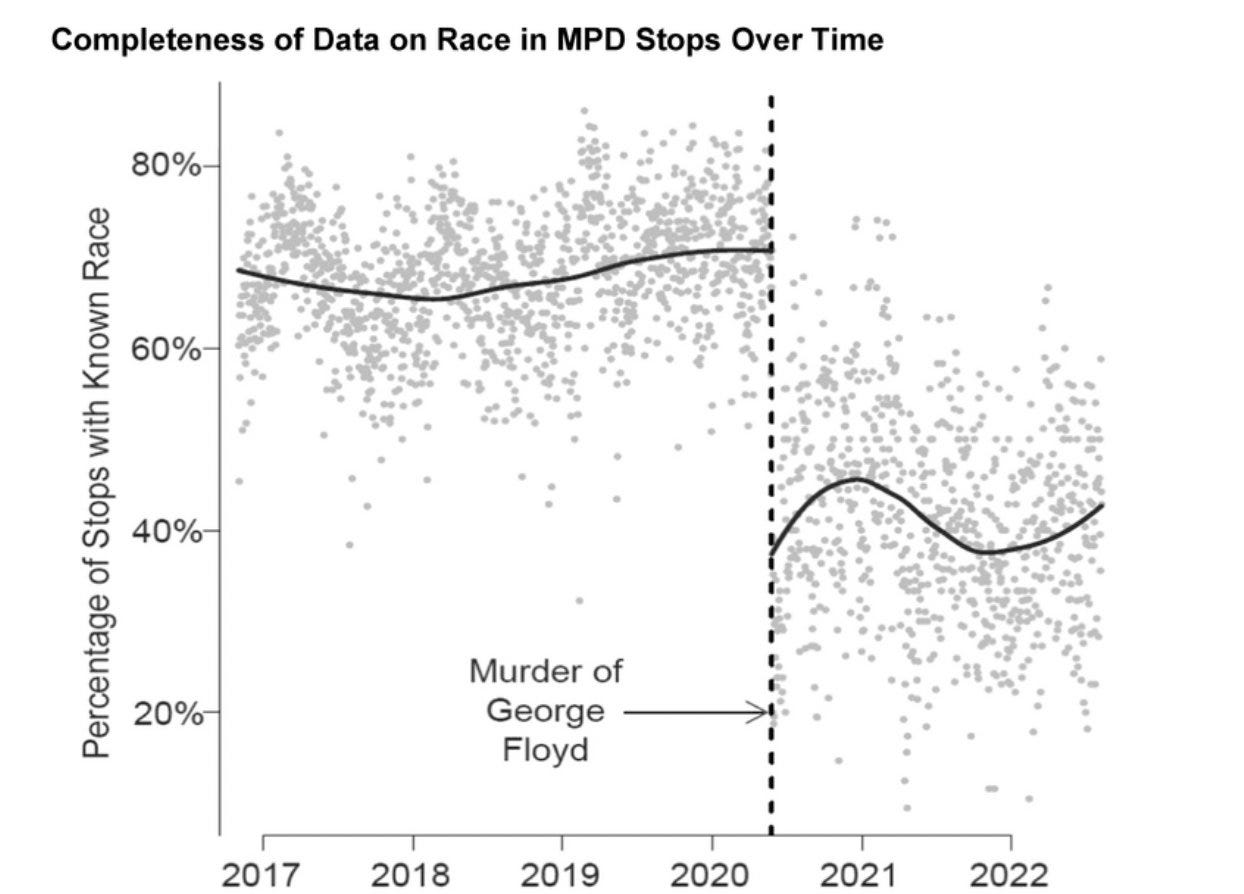

This next graph is really remarkable. After George Floyd’s death, MPD officers undoubtedly knew that their habit of racial profiling would be scrutinized. So many of them simply stopped documenting the race of the people they pulled over.

Then there are incidents like this:

Believe it or not, this isn’t even the only recent example of a racist Christmas tree at a police station.

One thing I’ve personally experienced since Floyd’s death is that black cops have become more willing to talk about systemic racism in policing. Several stories I’ve written in recent years originated with a tip from a black police officer.

Much of the time, though, these officers will only speak off the record. This is why:

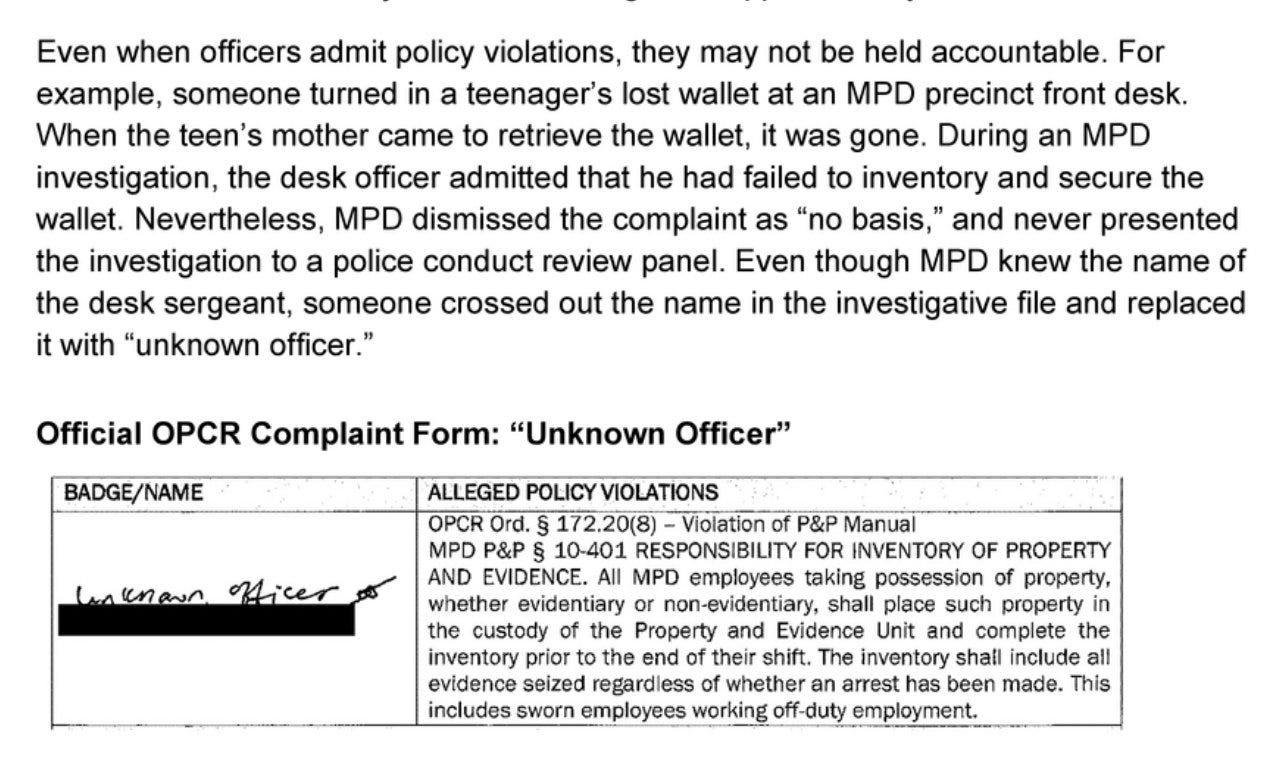

The DOJ report also found systemic problems with how MPD investigated allegations of police abuse and misconduct. It found that investigators often didn’t bother to interview witnesses, complainants, or the officers accused. In one incident, involving a complaint from a woman who says she was restrained and denied treatment as she suffered a diabetic emergency, investigators took the accused officers at their word despite video showing them mocking the woman. When the woman told the officers she was going into diabetic shock and couldn’t see, they put her in a restraint wrap.

If you read this newsletter regularly, you know that qualified immunity makes it nearly impossible for people who sue police for constitutional violations to ever get in front of a jury. The DOJ report found multiple cases in which MPD investigators cleared officers of abuse, but a federal court later found the abuse so egregious that it denied qualified immunity. Here’s one of those cases:

Now look at how the MPD officer charged with investigating police misconduct handled this complaint:

The DOJ report found that even on the rare occasion that a complaint was sustained, the most common form of discipline was “coaching” even for serious abuses like false arrest, unjustified use of a taser, and brutality. It also found that in three of every four cases in which an officer was referred for coaching, the coaching never happened.

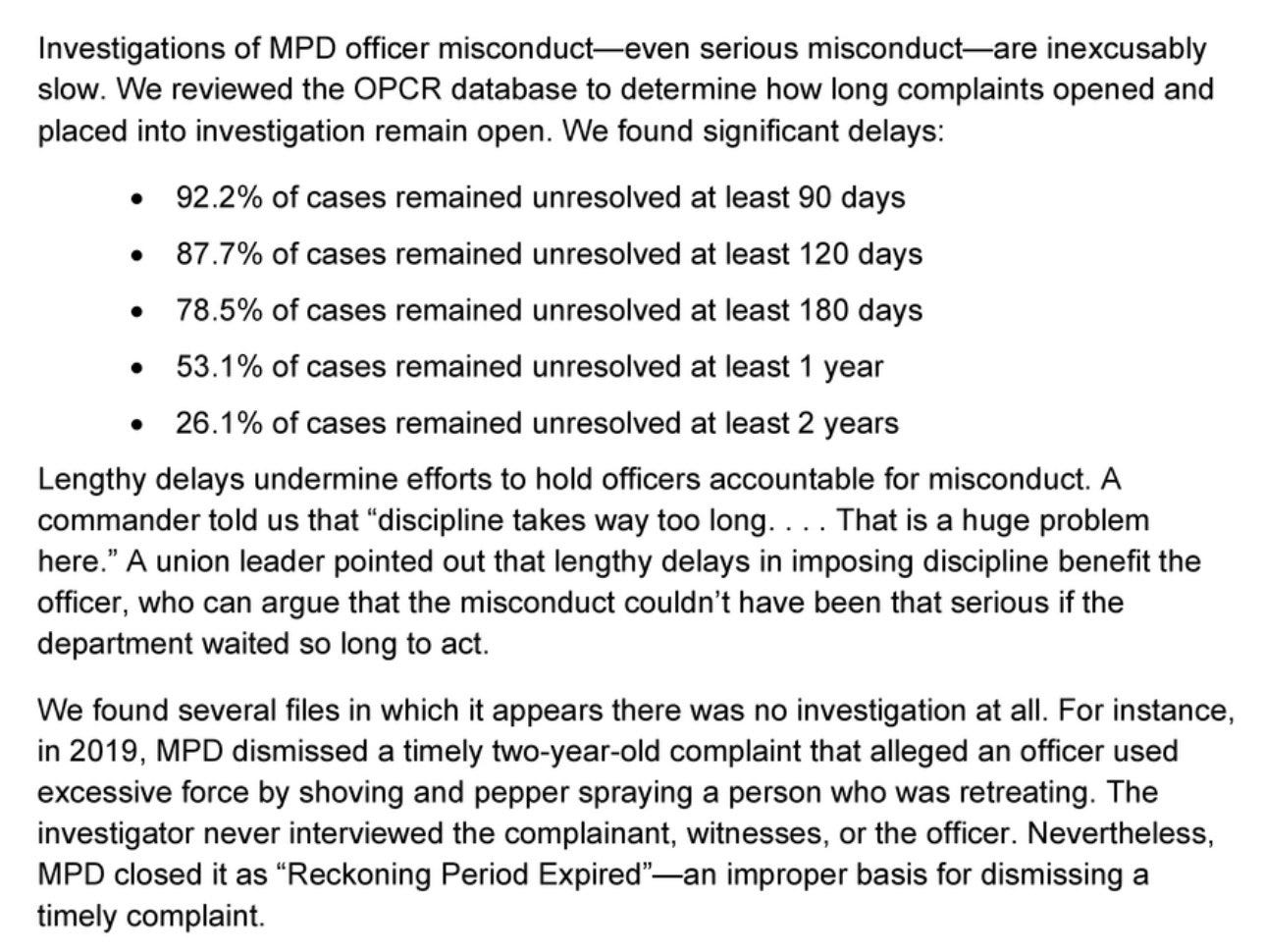

Remarkably, the DOJ report found that just 13.6 percent of complaints to MPD’s Office of Police Conduct Review resulted in an investigation. Over 65 percent were dismissed at intake. Many of these were dismissed despite body camera footage showing clear violations of MPD policy.

Among the 13.6 percent of complaints that were investigated, many were later dismissed because the department took too long to investigate.

Timeliness seems to have been a problem at MPD — so delay the investigation for as long as possible, then dismiss the complaint for being too old.

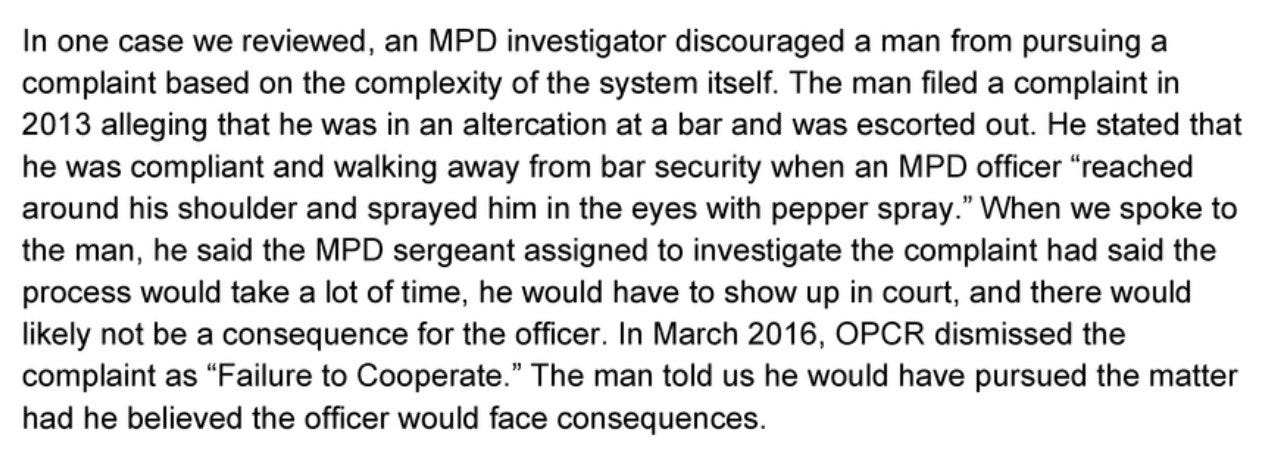

It gets worse. MPD officers apparently knew the system was hopelessly broken. So they used its brokenness to cover for one another.

At some point, the corruption is brazen that it’s almost comical, as in this case:

Police advocates often bristle at the word “systemic,” which they say suggests that all cops are corrupt, racist, or abusive. This tends to devolve into a pointless debate about “bad apples” — about how many cops are good and how many are bad.

This misses the point. The aphorism they’re butchering is “one bad apple spoils the bunch.” If you don’t remove the bad apples, the rot spreads. The proper question isn’t “How many cops in this department are bad?” it’s “Is this police department capable of detecting and removing the clearly rotten apples?”

It seems clear that MPD was not. The report discusses one officer who was found to have routinely committed illegal searches, was “overly aggressive,” and had multiple excessive force complaints. MPD finally suspended him two years later. The following year he was indicted on federal charges, including obtaining drugs for his own use after seizing them during illegal searches.

Meanwhile, starting in 2016, the homicide clearance rate at MPD went into a free fall, dropping to a low of 38 percent in 2020. I can’t find a specific clearance rate the murders of black people specifically, but in Minnesota overall, the 2019 clearance rate for murders with black victims was 30 points lower than the clearance rate for white victims.

The DOJ report about MPD just confirmed what marginalized communities in the city had been complaining about for years. Black people in Minneapolis had to coexist with a police department that disproportionately pulled them over; disproportionately searched them; disproportionately used force against them; excused, ignored, or covered up clear evidence of racism and brutality; rarely investigated citizen complaints; and allowed even the most abusive cops to operate with impunity. And for all of that, it did a lousy job keeping them safe.

These protests are rarely about the incident that precipitates them.

The Chauvin defense no one wants

Floyd’s death also inspired media investigations of MPD. One Minneapolis TV station looked at 500 cases in which the city had settled a lawsuit alleging police misconduct. In about a quarter of those cases, “an officer was accused in court of falsifying a police report, omitting key details or failing to report their use of force altogether.” The station found several instances in which both police officers and the city stuck to their stories until they were directly contradicted by video or forensic evidence. It also found multiple incidents in which MPD officers, including investigators, turned off their cameras while responding to shootings by fellow officers.

An NBC news investigation found that over five years, MPD officers had rendered suspects unconscious 44 times after administering a chokehold, a figure police trainers described as “unusually high.” Most police departments have moved away from these sorts of holds, because it’s hard to administer properly, and doing so improperly can lead to injury or death. (This is how Daniel Penny killed Jordan Neely on the New York City subway.)

At the time of Floyd’s death, MPD policy permitted what it called conscious and unconscious neck restraints. Both could only be applied when a suspect was “actively resisting” and an unconscious restraint could only be used “for life saving purposes” or if a suspect was violently resisting.

The NBC report found multiple incidents in which officers violated these policies. Eve on the rare occasion that an internal investigation found an officer culpable, MPD brass sometimes intervened to exonerate the officer anyway.

The DOJ report, meanwhile, found 198 incidents over six years in which MPD officers used neck constraints, including several after the department banned them. (MPD banned them after Floyd’s death.) Such restraints are only supposed to be used on dangerous people, yet in 46 of the 198 cases the incident didn’t result in an arrest.

Some have argued that this is what Chauvin actually did to Floyd — that he was applying a neck constraint consistent with MPD policy. This is not persuasive. NBC consulted more than a dozen policing experts who said that Chauvin’s hold on Floyd “is neither taught nor sanctioned by any police agency.” That’s consistent with what police trainers and use of force experts have told me. The tactic we see in the videos — both the way Chauvin applies his weight and the extended period of time for which he does so — doesn’t fit any sanctioned chokehold or neck restraint.

But the main reason this argument fails is that when it would have mattered most, Chauvin himself never made it. At his trial, Chauvin’s lawyers didn’t argue that what he did was consistent with the neck constraint portion of the MPD manual. They argued that it was part of the “Maximum Restraint Technique,” a different tactic addressed in a different part of the manual that I’ve already discussed at length in the first two parts of this series.

What the NBC investigation does show is that MPD was lax about enforcing these rules — just as it was about enforcing other department policies. It’s not hard to see why Chauvin would have either consciously ignored MPD policy, or just never bothered to familiarize himself with it.

MPD’s history of lax enforcement extends to Chauvin himself. He was the subject of 18 misconduct complaints, only two of which resulted in discipline (in both cases, a letter of reprimand). On three occasions, Chauvin was accused of restraining a suspect with his knee in a manner similar to what we saw with Floyd. In one 2017 incident, he hit a 14-year-old black boy in the head with his flashlight with enough force to require stitches, then knelt on the boy’s back and neck for more than 15 minutes. Federal investigators reviewed body cam footage and determined that the boy was cooperative and that Chauvin had used dangerous and unjustified force, then mischaracterized the entire incident in his police report.

But that was only after George Floyd’s death, three years later. In all three other incidents, the victims of Chauvin’s abuse filed complaints with MPD. Until Floyd’s death those complaints went nowhere.

Ironically, this is probably the one defense of Chauvin that has some weight — MPD rarely punished officers for anything, including brutality that should have been charged as a crime. The department made appropriate (if outdated) distinctions in its manual and training between various neck restraints, but then rendered those distinctions meaningless by failing to enforce them. In this sense, Chauvin was singled out, and his criminal prosecution was selective — at least in that it was the one time the city actually enforced policies designed to protect residents from dangerous tactics. Chauvin’s prosecution was the result of a state finally responding to anger over its failure to oversee law enforcement.

But this argument would also require Chauvin’s defenders to admit that policing in Minneapolis was fundamentally broken. So it isn’t one they’re willing to make.

Flattening an ugly history

In the first two installments of this series, I’ve been pretty hard on Coleman Hughes, the columnist who wrote about Chauvin, Floyd and the documentary The Fall of Minneapolis for the Bari Weiss-founded publication the Free Press.

I’ve focused on Hughes’s column for a few reasons. First, the Free Press positions itself as a voice of reason and rationality in a media ecosystem corrupted by “wokeism.” Second, Hughes is widely touted by conservatives, moderates, and contrarians as a smart, skeptical voice. And third, his column promoting TFOM typifies how such self-declared heterodox thinkers have latched onto the conspiracies about Floyd’s death that true skeptics should have seen through with even the slightest bit of research.

There was every reason to be skeptical of TFOM. It was produced by the wife of the former head of the Minneapolis police union, a former cop, and a far-right media outlet called Alpha News.

Some readers scolded me for using phrases like “far-right.” I don’t think this is an inappropriate description of Alpha News. The outlet was founded by a conservative activist, and has regularly platformed conspiracy theories about the COVID pandemic, including a steady drumbeat of stories about people who claim to have suffered strokes and other injuries allegedly caused by vaccines. Alpha News celebrated its hiring of a reporter who left a previous job because she refused to be vaccinated, and its Facebook account posted a cartoon suggesting COVID was a plot to get Democrats elected.

In 2021, Alpha News sponsored an event featuring right-wing activist Kim Crocket, a failed candidate for Minnesota secretary of state who ran on an “election integrity” platform and was suspended from a conservative think tank for making racist comments about Somali refugees.

The media watchdog site Media Bias/Fact Check categorizes Alpha News as “extreme right,” citing “extreme right bias, poor sourcing of information, promotion of conspiracy theories, and anti-Islamic propaganda, as well as a lack of transparency regarding ownership.”

None of this in and of itself means the claims in the documentary are wrong. It just means that given the personalities, donors, and publication involved, it’s probably wise to verify the film’s claims before amplifying them. And as I think I’ve already established, Hughes didn’t do that.

Instead, Hughes engaged in some flattening of his own.

From his column:

The producer of the film, Liz Collin, was a successful reporter and anchor at WCCO, Channel 4, in Minneapolis for many years before the death of George Floyd derailed her career. The sticking point was that her husband, former lieutenant and president of Minneapolis police union Bob Kroll, defended the four officers who arrested Floyd, denounced the rioters, who had recently captured and burned down a police precinct, as a “terrorist” movement, and highlighted Floydʼs long rap sheet in a letter to police union members. Both Kroll and Collin received an intense cancellation—including a protest outside their home—which led WCCO to push Collin out of her anchoring job, and eventually led her to leave WCCO and join Alpha News. While there, she teamed up with the filmʼs director, Dr. JC Chaix, a former police officer and volunteer firefighter, to make The Fall of Minneapolis.

This is certainly one way to describe Kroll, Collin, and their arc in this story. Here’s another:

Kroll was a 30-year police officer with MPD. He was first accused of brutality in 1994, just five years into the job. He faced another accusation in 1995 after an incident in which he was also accused of using racial slurs. In 2002, Kroll was named in a lawsuit after leading a raid in which officers were accused of brutality and excessive force against a Native American family. In 2003, he was again disciplined for misconduct. The following year he was suspended for brutality after he and other plain clothes officers beat a black man who had brushed up against their car. They also beat the man’s friends and punched the man’s sister in the face. While attending a class he was required to take as part of that suspension, Kroll called then-Rep. Keith Ellison, who is Muslim, a “terrorist.” He was later suspended for using a homophobic slur to describe an aide in the mayor’s office.

In 2005, Kroll was named in a racial discrimination lawsuit filed by four black officers, one of whom would later become MPD’s police chief. That lawsuit, too, accused Kroll of making racial slurs. It also alleged he was a member of an off-duty motorcycle club with a long history of racism. Kroll acknowledged his membership in the club, but denied it was racist, though the lawsuit alleged that Kroll himself had a white power patch sown into his club jacket. Kroll was again accused of brutality in 2006.

Despite all of this, Kroll served on the MPD SWAT team and vice unit, two highly-sought and prestigious positions. He also served on the public housing unit, which I think is self-evidently problematic for an officer with his history.

As Deadspin writes, by 2015 Kroll “had racked up 20 complaints with internal affairs and four letters of reprimand and was the subject of multiple Internal Affairs investigations. Only three complaints resulted in discipline.”

This was the year Kroll’s fellow officers elected him to lead the police union. Kroll’s history was well-known at the time, and was documented in an investigation by the Minneapolis Star-Tribune. It speaks volumes that Kroll’s fellow officers decided this was the man they wanted to represent their interests.

As head of the union, Kroll then wielded enormous power, not only to speak on behalf of the city’s police force, but to negotiate the policies that govern discipline, accountability, and transparency — the very policies the DOJ report found to be dysfunctional.

Kroll’s union tenure went as you might expect. In 2016, MPD officers who worked security for the Lynx — the Minneapolis WNBA team — walked off the job to protest players for wearing Black Lives Matter shirts during warmups. Kroll commended the officers, suggesting that people who exercise speech that cops find offensive aren’t worthy of police protection.

The same year, a Minneapolis-area police officer shot and killed Philando Castile during a traffic stop. Castile had done nothing illegal during the stop. It later came out that the officer had recently attended “bulletproof warrior” training, which teaches cops to override our initial reluctance to take a human life (in one seminar, an instructor tells his class that after killing someone, police can expect to have the best sex of their lives). Mayor Jacob Frey subsequently barred officers from attending these classes. Kroll responded by promising that the union would pay for any officer who wanted to attend.

Despite Kroll’s history of quickly jumping to the defense of officers after fatal shootings, he was silent for months after Somali-American officer Muhammed Noor shot and killed Justine Diamond, a white woman who had called 911 to report a possible assault.

This is an extensive history. And it wasn’t difficult to find. Maybe — just maybe! — the activists’ push for Kroll’s ouster wasn’t a hysterical attempt to “cancel” him for his speech, but an entirely rational realization — informed by 30 years of history — that a man with Kroll’s record shouldn’t be a police officer, much less lead negotiations on behalf of all MPD officers when formulating MPD policy.

Despite his own history of expressing some skepticism about police unions, Hughes doesn’t mention any of this. Instead, he flattens the activists’ argument into “an intensive cancellation.”

As part of a settlement with the ACLU over the treatment of protesters after Floyd’s death, Kroll is now barred for 10 years from working at any police department in the metro Minneapolis area. He’s also barred from serving on the Minnesota Board of Peace Officer Standards and Training. For what it’s worth, the ACLU made clear in a press release that the intent was to remove someone with Kroll’s record of abuse from a policymaking position that wields considerable power. It wasn’t to censor him for defending police officers.

As for Collin, the TV station she worked for has been quiet about what happened. I’m generally uncomfortable with the idea of demanding that people account for the actions of family members, even spouses. But if you’re a journalist covering an issue in which your spouse is a prominent player, disclosure seems wise, and activists say Collin reported at least one contentious story about city policing without disclosing her relationship with Kroll.

But more to the point, I’d argue that if TFOM is indicative of the journalism Collin did in Minneapolis, the station would have been justified in letting her go for that reason alone.

The threat to reform

As I mentioned in the first installment, the public outrage and protests over George Floyd’s death moved public opinion in a way we’ve never seen before. It also sparked real, substantive reforms. Cities and, in some cases, entire states passed policies prohibiting no-knock raids and chokeholds, creating police misconduct databases, mandating deescalation training, requiring body cameras, and funding programs to replace police officers responding to people in crisis with mental health professionals. (Despite the ongoing joke among police advocates about “sending a counselor” to deal with dangerous people, these programs have been enormously successful.)

But we’re now seeing a push to roll back many of these reforms. There has been some pushback even from progressive politicians and city councils, but it’s mostly been in red states, where conservative lawmakers have passed extreme legislation curtailing the right to protest, limiting criminal and civil liability for people who run over protesters, restricting public and media access to body camera footage, barring police agencies from releasing the names of officers who kill people or are accused of misconduct, and blocking public access to police personnel files. As we’ve seen here in Tennessee, deep red state legislatures seem determined to override reforms passed by their cities — or to prevent cities from attempting them in the first place.

The narrative that the 2020 protests were all based on a lie provides justifications for these laws. But I want to focus on a less-publicized, yet critically important area where Floyd’s death sparked reforms that are now being threatened — forensic pathology and death investigations.

As I pointed out in part two of this series, a medical examiner’s manner of death determination can be enormously consequential. The difference between categorizing an in-custody death as a homicide versus a natural or “undetermined” death often decides whether police officers will face criminal investigation, whether the family of the deceased will have cause for a lawsuit, or if the police agency involved will reexamine any policies that may have contributed to the death.

We also know that medical examiners face immense pressure, are often perceived to be on the same “team” as law enforcement, and can be influenced by cognitive bias. In one of the first studies to test cognitive bias among medical examiners, researchers found that when given otherwise identical autopsy reports, participating pathologists were more likely to rule an infant death a homicide when told that the child was black and that the last person to care for the child was the mother’s boyfriend, than when told the child was white and the last caretaker was a grandmother.

“I’ve seen medical examiners say things like, because of the color of the decedent’s skin, they couldn’t tell if there were bruises,” Joye Carter told me. Carter, the former chief medical examiner in Washington, D.C., was the first black woman to hold a chief ME position in the country. Carter had tried for years to get the National Association of Medical Examiners to start a diversity, equity, and inclusion program. “When I’d tell that story to explain why representation of nonwhite people is important, they would just shut down. They didn’t want to hear it. They just hear that as you calling them racist.”

Her idea received so little interest that she eventually resigned from the organization in frustration. But after Floyd’s death, NAME reached back out to Carter. She is now working with the group to educate medical examiners about the role of race in death investigations.

Carter’s efforts are just one of many similar DEI programs to get a new look after the 2020 protests. But the right has since pushed back with an effort to demonize DEI, and the effort to exonerate Chauvin is part of that backlash.

Carter’s efforts are far from the caricature of DEI you see from activists like Chris Rufo. It’s about making sure white medical examiners don’t overlook bruising when performing autopsies on black people. It’s about acknowledging and mitigating the cognitive bias that can taint profoundly consequential decisions. It isn’t about white guilt. These are life and death issues.

There’s another area in which forensic pathology is in need of urgent reform that is especially relevant to the Floyd case — the competing diagnoses of excited delirium and positional asphyxia. Both of these diagnoses can be used to explain why someone may have died in police custody. But only one condition is rooted in reality.

In the context of in-custody deaths, positional asphyxia occurs when a police restraint either cuts off airways, or compresses the diaphragm in a way that only allows for shallow breathing. This inhibits the ability to both take in oxygen and expel carbon dioxide, both of which can be fatal. Positional asphyxia is preventable — it is up to police departments to train officers on how to avoid it.

Excited delirium, on the other hand, posits that some people just spontaneously die during intense, high-stress interactions with police, through no fault of law enforcement. It’s also highly dubious and not supported by any major medical organization.

Over the last several decades, there’s been a concerted effort to pressure medical examiners to diagnose excited delirium when the real cause of death was positional asphyxia. This not only exonerates cops who kill, it encourages police practices that will lead to more deaths.

George Floyd’s death prompted renewed scrutiny of excited delirium and its origins. This was overdue.

The first reason to be skeptical of the condition is that it’s rarely if ever diagnosed outside a law enforcement context. If there really is a condition that causes people to die spontaneously during a mental health crisis, while under the influence of some drugs, or while panicked with no accompanying signs of medical distress, we ought to see it under other high-stress, volatile scenarios like street or bar brawls, or when people are forcibly admitted to psychiatric facilities. This just doesn’t happen.

The origin of excited delirium is shonky and steeped in bigotry. But it doesn’t involve police or police restraint. The condition was first described in the mid-1980s by Miami medical examiner Charles Wetli after a wave of black sex workers were found dead under mysterious circumstances. Because some of the women had cocaine in their system, Wetli theorized that there must be something about the physiology of black women that causes them to spontaneously die after mixing cocaine with sex.

Despite the absurdity of Wetli’s theory, it precluded homicide as a manner of death, which made it much more difficult for police to investigate the possible murders. It wasn’t until a victim was found in a similar state as the other bodies, but had no cocaine in her system, that the city’s chief medical examiner reviewed the doctor’s work in the other cases. He found evidence of asphyxiation that Wetli had overlooked. Police eventually arrested a serial killer named Charles Henry Williams for the murders. Williams is now believed to have killed at least 32 black women through asphyxiation.

Joye Carter was doing a fellowship in the Miami office when all of this went down, and in interviews has said that as one of just a few black women medical examiners, watching Wetli’s nutty, racist theory become a widely accepted cause of death was a formative experience.

The Miami debacle should have been an embarrassment that ended Wetli’s career. It did not. The controversy isn’t even mentioned in his fairly long New York Times obituary. Instead, he failed upward, becoming the chief medical examiner in Suffolk, County, New York.

In the absence of any accountability, Wetli continued to develop his theory in ways that proved convenient for law enforcement. He expanded excited delirium to also include black men, particularly those who die in police custody. “Seventy percent of people dying of coke-induced delirium are black males, even though most users are white,” he once said. Instead of concluding that perhaps this was because police were more likely to use excessive force against black men, Wetli added, “It may be genetic.” The diagnosis has since expanded to include “exhaustive mania,” a form of excited delirium that, conveniently, occurs in people who haven’t ingested drugs or alcohol.

Wetli’s work eventually landed him a lucrative side gig with Axon International, the company that makes the Taser (formerly known as Taser International), who began to pay Wetli to testify as an expert witness at the trials of police officers accused of brutality.

Over the next several decades, Axon would mount a well-funded, full court press to legitimize excited delirium in academia, the courts, and in forensic pathology, while threatening to sue researchers and medical examiners who attributed in-custody deaths to Taser use. The company paid consultants to write papers justifying excited delirium as a cause of death, often without disclosing their relationship with the company. Axon also paid for expert witnesses to testify in police brutality cases, and urged police departments to consult with experts on its payroll after in custody deaths. One such analyst is Deborah Mash, a now-retired protege of Wetli who claimed to have developed a test that can detect “biomarkers” of excited delirium in brain tissue (subsequent studies found that these biomarkers may just indicate drug use). A Reuters investigation found cases in which Axon representatives strongly urged police officials to send brain tissue to Mash after in-custody deaths.

By 2003, the L.A. Times reported, excited delirium had been diagnosed in a majority of in-custody deaths.

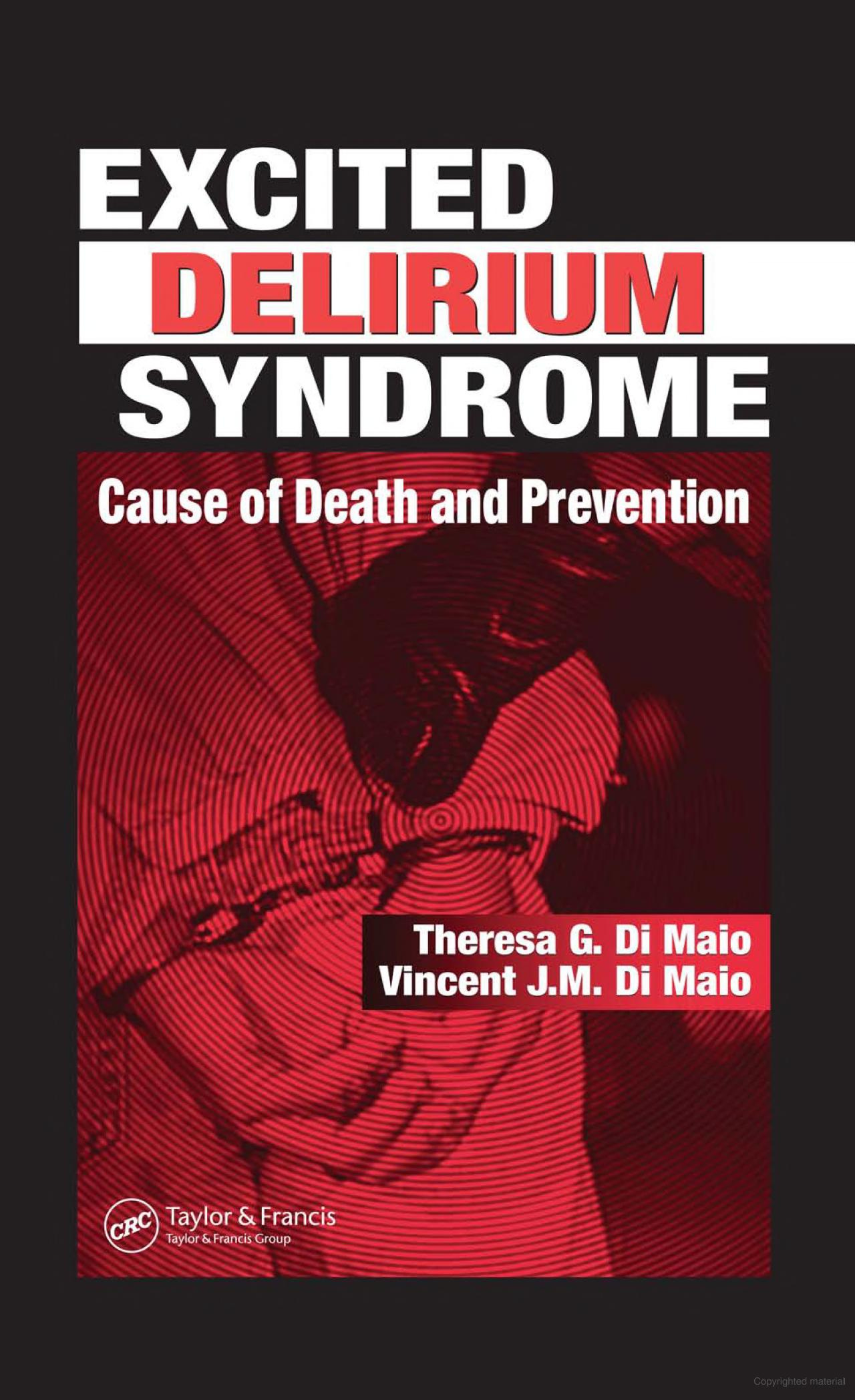

Perhaps the only figure to do more than Wetli to popularize the condition was celebrity medical examiner Vincent Di Maio, who may be best known for testifying for the defense at George Zimmerman’s trial. In 2006, Di Maio and his wife wrote a book championing excited delirium. The two dedicated the book to “all law enforcement and medical personnel who have been wrongfully accused of misconduct in deaths due to excited delirium syndrome.”

Axon purchased more than 1,000 copies of the book — more than enough to give one to every medical examiner in the country — and distributed them at forensic pathology conferences.

Excited delirium has never been recognized by the American Medical Association, the American Psychiatric Association, or the World Health Organization. In fact for years, just two major medical groups endorsed the theory: the National Association of Medical Examiners (NAME), and the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP).

These groups’ embrace of excited delirium was based on a 2009 paper published in the ACEP’s journal following the “3rd Annual Sudden Death, Excited Delirium & In-Custody Death Conference” in 2008. That conference was put on by a group called the Institute for the Prevention of In-Custody Deaths, which had been founded a few years earlier by the national litigation counsel for . . . Taser International.

The 2009 paper argued that excited delirium “is a real syndrome of uncertain etiology,” with symptoms that include sweating, rapid breathing, pain tolerance, unusual strength, and “police noncompliance.” Three of the authors — including Deborah Mash — were consultants for Taser (now called Axon), which the journal failed to disclose.

The lead author of that study — an emergency room physician named Jeffrey Ho — wasn’t just a consultant for Axon, he was the company’s “medical director.” According to Reuters, in 2015 Axon paid Ho’s employer, the Hennepin County Medical Center (HCMC), $250,000 to create and fund a new position for him. (In an odd twist of fate, this would be the hospital where George Floyd was pronounced dead.) Axon paid Ho an additional $70,000 per year to testify for the company in lawsuits, and gave him about $1 million in stock. Ho is also a part-time deputy with the Meeker County Sheriff’s Office in rural Minnesota.

Ho has also written papers encouraging forcibly injecting ketamine into people suffering from excited delirium, a tactic opposed by the American Medical Association. In 2018, the Minneapolis Star-Tribune revealed that HCMC staff and EMTs had been injecting people with ketamine who didn’t pose a threat, often at the explicit request of police officers. According to the Star-Tribune, the number of people injected with the drug jumped from 2 in 2010 to 62 in 2017. Rather than respond to the news report, MPD mocked the findings in training materials, which included a quote from Ho.

The Hennepin County Medical Center ended the relationship with Axon in 2019 after backlash from activists.

There is no diagnostic test for excited delirium. Instead, it’s become a catch-all diagnosis based on a broad range of symptoms and behavior that could be attributed to any number of conditions — symptoms like erratic behavior, psychosis, public nudity, and, weirdly, a tendency to propel oneself through glass.

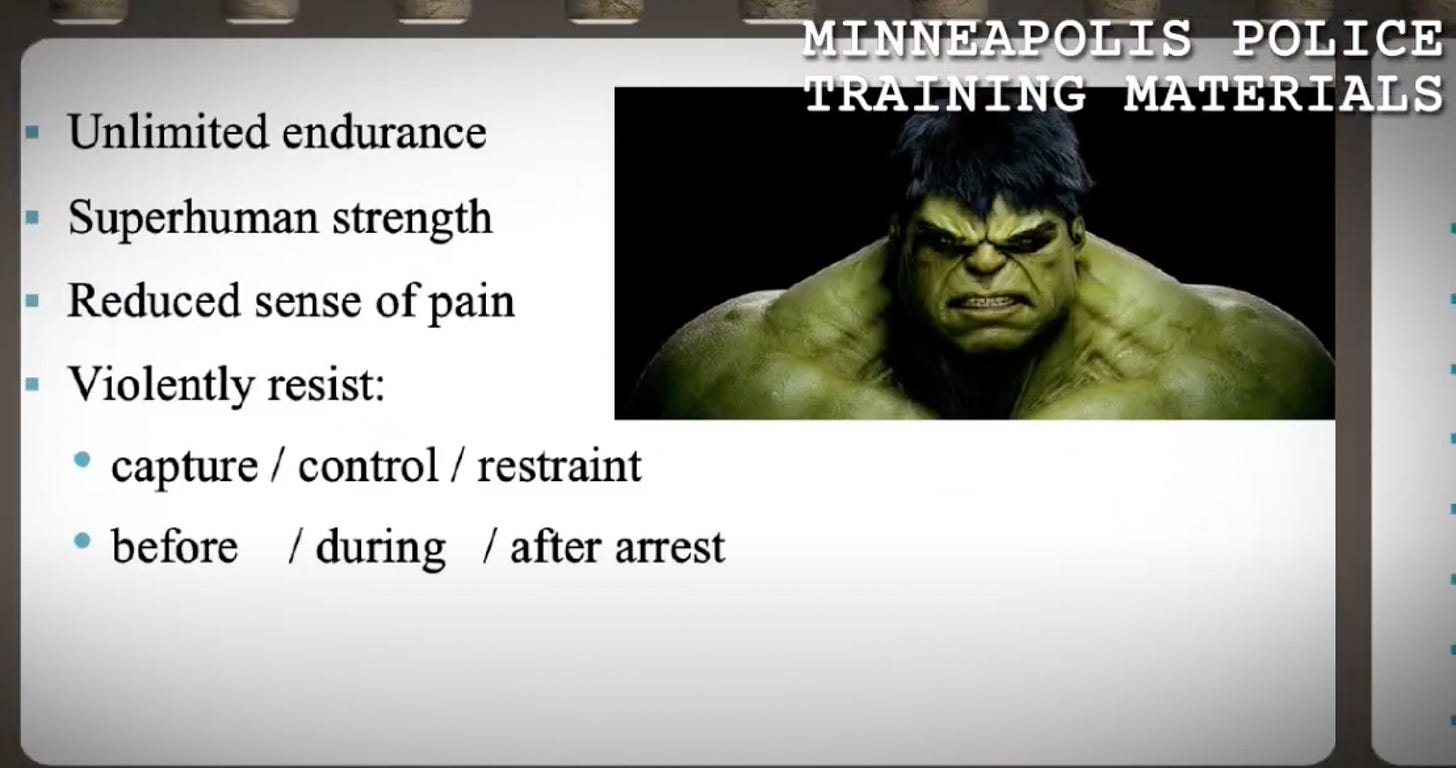

But the most absurd supposed symptoms are an imperviousness to pain and “superhuman strength.”

There are obviously some drugs that can dull a user’s sensitivity to pain. And a rush of adrenaline can prompt a person to run faster or lift more weight than they otherwise might. But the idea that excited delirium can give people near-superpowers has been incredibly harmful. The claim doesn’t merely excuse brutality, it practically demands it. It also reinforces racist tropes about the brutishness of black men.

There’s good reason to believe these myths were factors in the death of George Floyd. Recall that during Floyd’s fatal encounter with Chauvin, MPD Officer Thomas Lane is heard on body cam audio asking if they should roll Floyd onto his side. When Chauvin says no, Lane responds, “Okay. Just worry about the excited delirium or whatever.”

During his trial, Chauvin’s attorneys argued that his fear of excited delirium was precisely why he knelt on Floyd for as long as he did.

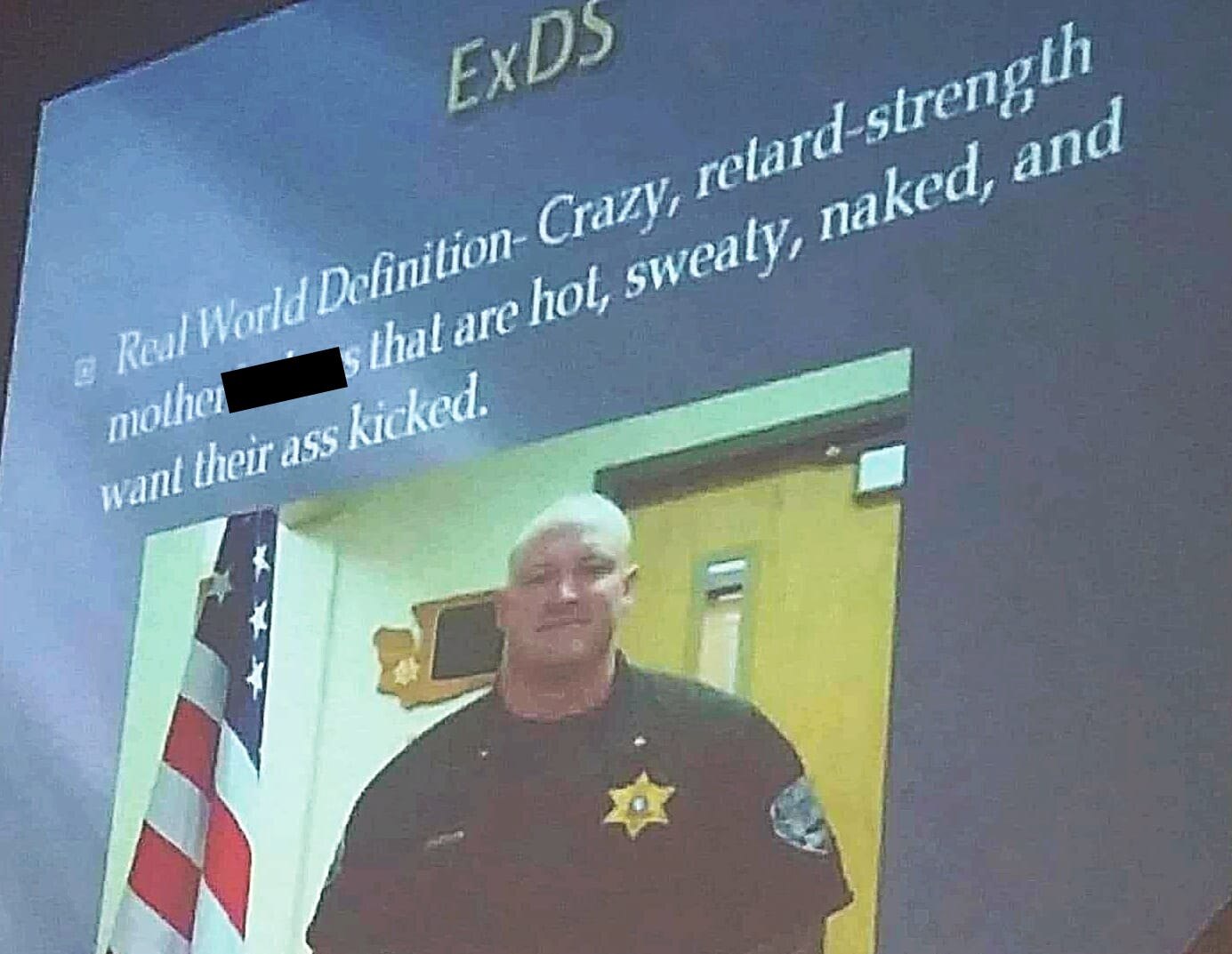

In 2021, Fox 9 in Minneapolis obtained the training materials that the Minneapolis Police department had been using for excited delirium.

Here, incredibly, is one of the training slides:

Here’s another, which calls excited delirium the “main culprit” of in-custody deaths:

A few months after Floyd’s death, the journal Forensic Science, Medicine, and Pathology published a review of deaths attributed to excited delirium. It found “no existing evidence that indicates that excited delirium is inherently lethal in the absence of aggressive restraint.” The authors concluded:

. . . the more likely it is that a death resulted from restraint, the more likely it is that the death will be attributed to [excited delirium], which allows for the restraint to be ignored as a cause. Thus, the evidence suggests that [excited delirium] is not a unique cause of death in the absence of restraint, and that the supposition to the contrary is an artifact of circular reasoning and confounding rather than an evidence-based inference.

“Arrest-related death syndrome”

At the same time that excited delirium was being pushed on the courts and medical community, law enforcement interests were mounting a campaign to discredit positional asphyxia as a cause of death for people in police custody.

To be clear, there is nothing controversial about positional asphyxia. It’s long been an accepted cause of death after incidents like car accidents or falls in which someone ends up in a position where they’re physically restricted from breathing properly. As I documented in the first part of this series, police departments around the country have long trained officers that putting weight on a suspect’s back while they’re prone and handcuffed is dangerous and can be fatal.

The problem is that a small group of law enforcement-connected researchers in San Diego have given the courts the academic heft they need to clear police officers of liability when they asphyxiate someone in their custody.

Here’s the New York Times’s Shaila Dewan in 2021:

The studies began after the death of a 35-year-old man named Daniel Price, who was high on methamphetamine when he was subdued by four San Diego sheriff’s deputies in June 1994. They pepper-sprayed him, wrestled him to the 134-degree pavement and hogtied him. The autopsy cited “maximum restraint in a prone position by law enforcement.”

When Mr. Price’s family filed a lawsuit, the county turned to doctors at the San Diego Medical Center for help.

At the time, it was widely accepted that prone restraint, used to subdue combative or disorderly people, could be lethal. It compresses the torso and restricts breathing, potentially leading to what is referred to as positional asphyxia or restraint asphyxia.

Many police departments had already banned the most extreme form of prone restraint, hogtying, and in 1995 the Justice Department warned of its dangers.

The San Diego doctors proposed a study, paid for in part by the county, that would measure the effects of hogtying in controlled laboratory conditions.

More studies followed casting doubt on positional asphyxia from police restraint, all from the same group of researchers.

There are lots of problems with these studies, starting with the fact that they tend to contradict research not funded by law enforcement interests. The biggest and most obvious problem, though, is that a controlled lab experiment on healthy subjects who know their safety is secured can never replicate the physiological responses associated with the stress, chaos, and fear of a heated police encounter.

It’s also worth exploring the biographies of these researchers, which a 2021 New York Times investigation called “a cottage industry of exoneration.” One co-author of a study casting doubt on positional asphyxia, for example, is emergency medicine doctor Gary Vilke, now at the University of California-San Diego. According to a 2023 report, Vilke had testified 58 times over the previous four years, often at the behest of Axon, and could make up to $50,000 per case. He told the Times that for at least the last 20 years, he had exclusively testified in defense of police officers accused of misconduct. Vilke was also one of the co-authors of that 2009 study on excited delirium. In 2020, Vilke’s grand jury testimony helped persuade jurors not to indict Rochester police officers for the death of Daniel Prude. Vilke told jurors that Prude died of excited delirium.

Another of the authors of the positional asphyxia study is Mark Kroll, an electrical engineer. Kroll currently sits on the board of Axon, collecting a $300,000 per year stipend. He’s also affiliated with the Force Science Institute, the highly suspect group that tells police they should be shooting people more quickly and more often, and whose experts regularly testify at police brutality trials, always reaching the conclusion that officers’ actions were justified. In 2019, Kroll gave a webinar for Lexipol, the company that writes policy for police departments all over the country, revealingly titled: “Arrest Related Deaths: Managing Your Medical Examiner.” (Oddly, Lexipol — which writes policy for thousands of police agencies, including 95 percent of the departments in California — also produces material that criticizes excited delirium, and encourages police to be vigilant about positional asphyxia.)

When Minneapolis TV station KARE reached out to Kroll about his work on this issue in April 2021, Kroll replied, “I did some minimal research on this a few years ago and am no longer active in the area.” Eight months later, Kroll published a paper titled, “The Dying Gasps of the Prone Asphyxia Hypothesis.”

The New York Times review found that this network of researchers consistently shifts blame for in-custody deaths away from police — and that three of every four studies of in-custody deaths that are favorable to police were written by one or more people from this network. Here, for example, is a typical article on a pro-law enforcement site by Kroll, Vilke, and Ho, this one published about a year before George Floyd’s death.

If you read this newsletter much at all, you won’t be surprised to learn that the courts have done a pretty lousy job evaluating all of this. The courts embraced excited delirium early on in dismissing lawsuits against police officers. But in recent years, the families of people who supposedly died of excited delirium have filed lawsuits sensibly arguing that, if excited delirium is real, the diagnosis has now been around long enough that police should be trained to recognize it and take steps to prevent people from dying of it. Not surprisingly, in these cases, the courts have been a lot more willing to entertain the idea that perhaps excited delirium isn’t a science-based condition after all.

The courts were also quick to embrace the positional asphyxia research by Kroll, Vilke, and the Axon network, despite ample research contradicting their claims. As we know from fields like bitemark analysis, because courts rely on precedent, once they accept a dubious line of research, it becomes difficult to persuade them to reverse course. Just last year, the U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear an appeal from an Eighth Circuit decision granting qualified immunity to St. Louis police officers who held a man in handcuffs and leg irons face down while an officer put weight on his back for 15 minutes. The man stopped breathing and died. Attorneys for the officers argued that the man’s struggle to find room to expand his diaphragm to inhale were attempts to “resist.”

The campaigns to push excited delirium and to suppress positional asphyxia feed off of one another. And they’ve clearly had their intended effect. A 2021 study in the Lancet found, incredibly, that 55 percent of in-custody police deaths since 1980 were mislabeled in a way that minimized the role of law enforcement. Another recent study of 168 deaths attributed to excited delirium found that every one of them involved some sort of police restraint. The lead author of that study, Michael Freeman, has said in interviews that he believes nearly all of these deaths were likely from positional asphyxia.

In the end, this means that though police are trained on the threat of positional asphyxia, there’s little accountability when they ignore that threat in the real world. Even as I was writing this, the Guardian published an investigation of 22 in-custody deaths of people in the prone position that cardiologists said could have been prevented with basic protocols, like rolling suspects onto their side.

George Floyd’s death started to change at least some of this. Last year, NAME and ACEP finally disavowed excited delirium. This means there are no longer any major medical organizations who endorse the concept. In response, last fall the California legislature prohibited excited delirium as a cause of death. The Lancet has also called for an end to the diagnosis.

We’ve also seen reevaluations of dangerous tactics like hog-tying and restraint chairs, and state reviews of how previous in-custody deaths were investigated. There’s also a reevaluation underway of the positional asphyxia research published by the Axon network, and an audit of in-custody deaths in Maryland. The LAPD disavowed police training by the Force Science Institute.

These reforms, like the reforms to policing more generally, are important, but they’re also modest and tenuous. Even if “excited delirium” is on its way out as a diagnosis (and we’re far from that point), it could easily be replaced with a different set of words that have the same effect — to exonerate police officers for deaths that should never have happened.

The social upheaval and demand for change in the summer of 2020 presented an existential threat to those who use the veneer of science to explain away police killings. It’s important to understand that The Fall of Minneapolis and the mainstreaming of its lies are part of that effort. It’s an attempt to use bogus science to explain away what was likely the most damning, potent, and consequential police killing in U.S. history.

This is all happening at the intersection of two issues I’ve covered my entire career — policing and dubious forensics. For 20 years I’ve watched the criminal justice system find new ways to excuse bad cops, often with junk science. The last few years have presented just the slightest bit of hope. I can’t tell you how aggravating it’s been to watch generalist pundits with little to no experience in these areas — people who describe themselves as skeptics — allow themselves to be duped by powerful interests seeking to blunt that momentum and preserve the status quo.

I’ve spent six weeks writing 30,000 words on this because what we’re seeing is dangerous. We should be perfectly clear about the ultimate goal of Axon, its network, and the people behind The Fall of Minneapolis: They want to make it easier for police to kill people without consequence.

If that sounds hyperbolic, consider what Axon board member, positional asphyxia skeptic, and police trainer Mark Kroll said during “Managing Your Medical Examiner,” the training session sponsored by Lexipol, the company that writes policy for police departments around the country:

“Decades ago we used to prosecute mothers for crib deaths and sudden infant death syndrome, and then we figured out it really wasn’t their fault . . . Hopefully in the future we’ll have something like sudden infant death syndrome, just ‘arrest related death syndrome’ so we don’t have to automatically blame the police officer.”

(*Addendum: Hughes has responded to this series. You can read my response to him here.)

Radley: Thank you for this series. Incredible, important work. A real service to the discourse of a kind that few people ever make.

There is just one element I wish was not in this latest piece and that is the casual swipes you take against the backlash against DEI.

It sounds from your description like Joye Carter is doing important work. I know for sure that Jennifer Eberhardt at Stanford is doing important work with police departments as well. I am huge fan of Eberhardt. I believe that if everyone in American read her amazing book "Biased" (along Jonathan Haidt's "The Righteous Mind") our country would be a far, far better place. Doubtless you have Carter and Eberhardt's type of work in mind when you're pushing back against the criticism of DEI.

But while I share your belief in the importance of this work, my own experience and research about DEI programs in the corporate workplace and everything I have read and heard about them in universities makes me believe that the criticisms of of these programs is warranted and that most of them are at best useless and at worst genuinely harmful.

So I think when you casually defend "DEI" in the way that you did you're making the exact same mistake Rufo did in the opposite direction. Both of you rhetorically combine all DEI programs into a single bucket. When Rufo does it, he is trying to discredit the good along with the bad. When you do it, you're (hopefully unintentionally) defending the bad along with the good. So I would hope going forward you'll be more precise in your defense of constructive DEI initiatives.

This whole series was so well done that I had to become a subscriber and support your work.