The redeem team

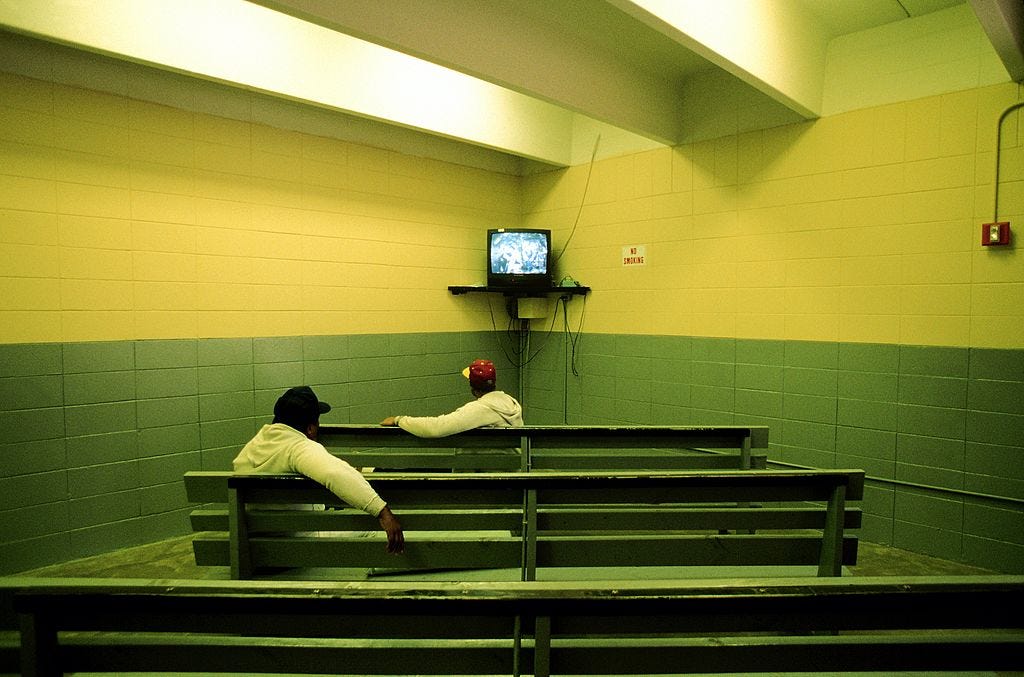

Collectively, they spent 155 years in prison. Now they counsel other people facing their own long sentences. A conversation with five "peer advocates" at the New Orleans public defender's office.

Of the five men who serve as “peer advocates” for the Orleans Parish Public Defender, only one — Robert Jones — is an exonoree. He was released in 2016 after the BBC uncovered evidence of his innocence. He had been convicted of a rape and robbery spree in the French Quarter that culminated in the killing of a British tourist. Jones now serves as director of community outreach for the office.

Another of the five, Terry Pierce, says he was acting in self-defense when he shot and killed a man in 1980. The other three — Michael Banford, Everett Offray, and Louis Gibson — do not claim that they were innocent.

While Jones was 19 at the time of the alleged crime, the other four men were convicted for murders committed when they were juveniles. All four were sentenced to life without parole, and all four were were among the hundreds of prisoners released after a series of Supreme Court decisions limiting when states can impose life sentences on minors, but before the more conservative Trump-era court began to narrow those decisions.

The peer advocate advocate is a relatively new position that you’ll primarily find in holistic public defender offices. The idea is to have formerly incarcerated people serve as counselors, advisors, and mentors to clients facing serious criminal charges. Their job is to build trust and facilitate communication between the accused and their legal team. Their responsibilities might include advising clients considering plea bargains, helping people recently released adjust to reentry, and preparing clients and their families for prison after a conviction.

I interviewed these five men last month while visiting public defender offices around the country as research my forthcoming book, The Defenders.

I wanted to share the interview now because we’re currently in the midst of a broad backlash against criminal justice reform, rehabilitation, and the very notion of empathy.

I also wanted to share it because I found these guys inspiring. They’re living proof that rehabilitation is real, that people really do age out of crime, and that, as Bryan Stevenson famously put it, we’re all so much more than the worst thing we’ve ever done.

I’ve edited the interview for clarity and length.

So I guess the first thing we can do is go around the table and have each of you introduce yourself and tell me a bit about how you ended up in this office.

Robert Jones: Sure. My name is Robert Jones. I served 23 years and seven months in prison for a crime I did not commit. While I was at Angola prison, I worked at the prison library, where I taught myself, studied, and practiced the law.

Before this office became the Orleans Public Defender’s Office it was called the Orleans Defender Program. And in that particular office, they lacked a lot of resources, staff, and what have you. So I used to file a lot of complaints against that particular office.

So you were a jailhouse lawyer — you were filing complaints on behalf of other prisoners?

Robert Jones: That’s correct. Most of the time for ineffective assistance of counsel. Lots and lots of complaints for ineffective assistance.

But over a period of years, I found I was filing less and less complaints against the New Orleans office. I eventually realized that this was because the office was turning into what it is today — which is to say, it’s a much better office. So when I got out, I came here to visit. And I saw that I was right — the office had changed. It had evolved into an office of passionate people who really fight for the rights of their clients. They eventually offered me a job as a peer advocate. I’ve stuck with it ever since.

Louis Gibson: My name is Louis Gibson and I served 25 years on what they call juvenile life without parole, and what I call death by incarceration. After a Supreme Court decision in 2012, they started making juveniles convicted at age 17 or younger eligible for parole and I got out. So I was 17 when I went to prison, and I came home at age 42.

The Louisiana Parole Project in Baton Rouge is the group that helped advocate for my release. They also had a reentry service. I thought I didn’t need any reentry service to integrate back to society. I thought, just let me go. I know what to do. I know how to survive.

But I had a lot of fears that I kept hidden. I’m not even sure I had admitted them to myself. How am I going to survive in society? Where am I going to work? Where am I going to stay?

That program taught me a lot. It taught me a lot about myself, and it helped me readjust. I took so well to it that I eventually started working for them. Soon enough, I was doing reentry services for other guys coming out who were similarly situated as me. I realized I was really good at helping guys understanding what they need, often without them even having to tell me.

After I was out for awhile, I heard about a position here in New Orleans, where I’m originally from, and I had been wanting to come back home. It was called the Resentencing Unit. The idea was that after the juvenile LWOP decision, you’d have a lot more guys coming out, and so there needed to be a unit to help with reentry. So that’s what brought me here to the public defender’s office. We started with the Resentencing Unit, and that turned into these client or peer advocate positions.

Now I serve as a youth advocate. And that’s really rewarding for me because I get to work with a lot of the kids inside the juvenile system.

Everett Offray: I’m Everett Offray. I did 27-and-a-half years of a life sentence. I got sentenced when I was 18, and came home when I was 45. While I was at Angola, I was blessed enough to work in the law library, where I started to learn the law and how it works. There’s so much that you just don’t know until you get in the system, and at that point it’s kind of too late. But as I learned more about the law, I also learned that there are a lot of people in prison who really don’t know what’s happening with their cases. They just lose track, and there’s no one to help them. So as I taught myself the law, I was blessed to able to help a lot of brothers regain their freedom.

In 2021, I was able to get out myself through the courts. The court said my lawyer was ineffective. All our lawyers were.

[They all laugh in agreement]

When I came home, I first got a job with a lawyer doing some paralegal work. And then a job opened up with the Resentencing Unit. It was a good fit, because I’d be doing the same things for people that I had been doing in prison. So I got hired at the public defender’s office and there too we were blessed to help a whole lot of brothers get out of prison.

The public defender program gave me structure. It taught me a whole lot of things that I didn’t know. When you’re a jailhouse lawyer you have to do everything for your clients. But in an office setting, you have teams that work on these cases. You have people who specialize in different aspects of these cases.

As a peer advocate, I get to talk to other people who were in the place I was once. I get to help them decide whether it’s in their best interests to go to trial or take a plea that lets them come home — but that will also have lifelong consequences. I’m in a position to educate people about the public defender office, but I’m also in a position where I can educate the lawyers about their clients. It can be hard for a lawyer to understand the perspective of someone who just did a lot of time in prison. And if you can’t fully appreciate what happened to your client, you can’t fully represent their interests. As a peer advocate, I can give these guys the perspective as someone who’s been through it, but I can also give that same perspective to the lawyers, which helps them better represent these guys. So that’s also a blessing.

Terry Pierce: I spent 41 and a-half-years in prison. When I got locked up in 1980, there were maybe three or four attorneys in the public defender program. They had one investigator.

I’m surprised there was even an investigator.

Yes, one guy. He was young, very flashy, and in my case, I know for a fact that he didn’t go investigate in the projects where I was raised.

I was 22 years old when I went to prison. Straight out the military. I was a first-time offender. Over the years, I kept banging my head against the wall trying to learn the law. Trying to learn how to fight my case. It was difficult, but I learned, and ended up becoming an offender counselor in the prison, helping other guys with their cases too.

As for my own case, I was finally able to demonstrate the combination of bad jury instructions, the non-unanimous verdict ruling from the Supreme Court, and ineffective assistance of counsel. I was able to negotiate a plea, and got 21 years credit for timed served.

This is my sixth month working here in the public defender office, so I’m fairly new. Robert Lewis put me in touch with the office. I filled out the application, went through the interviews, and I guess I passed muster because now I’m working here. My main job is communicating with guys who are incarcerated. Helping them understand their attorneys. Helping their attorneys understand them. Just facilitating communication between them. I think part of our responsibility is to help the attorneys in this office understand their clients from the perspective of someone who has been there. Communicating with someone in prison or facing a long sentence can be a difficult thing for an attorney to understand. They’ve never been through anything like that. Even after they’ve been on the job a while, had lots of clients, it can be challenging to understand what it’s like from the other side. I think my work as a prison counselor has helped a lot. Because we went through it with those guys we served with. That helped prepare me for the stresses of this job.

So were you all jailhouse lawyers at Angola?

[They all affirm.]

Michael Banford: I’m Michael Banford. I did 29 years of incarceration. Like Louis, the Louisiana Parole Project helped prepare me to become a productive citizen when I got out, and the same people helped me get this job as a peer advocate. It’s a joy for me because it’s basically the same thing we did in prison. At Angola, when an attorney couldn’t talk to a client because of something that happened between them — where they butting heads or whatnot — that’s where we would come in. We’d come in and settle the water a little. If there was something an attorney really needed the client to know and understand, they’d tell us and we’d work with the client. We’d also help them gather their records, papers, and everything else they might need for a good defense or to help with their appeal.

Prior to all of our incarcerations, you didn’t have this type of work in public defender offices. You had one attorney that you never saw. It’s so encouraging to see all the teamwork in this office. It makes you want to work harder, to go above and beyond. We know what we are doing, and we know that we are effective at what we’re asked to do. We all lean on each other, ask each other questions, feed off each other. We do all of that to help these guys who are sitting right where we were 20 or 30 or 40 years ago.

Can you talk about what reentry was like for you? How did you adjust?

Terry Pierce: Like I said, I negotiated a plea deal. So I wasn’t exonerated, but I also wasn’t on parole. So it might have been hard for me to get the benefits that either of those people would get. Fortunately the Parole Project accepted me into their programs to help me reintegrate. And thank goodness for that. For all my self-assuredness, after 41-and-a-half years behind bars I would have been lost.

Your family wants to help you in whatever way they can, but they don’t know how to deal with you. They don’t know everything you’ve missed in 41 years. So the Parole Project People helped me out a lot. They got me a phone, got me on Medicaid. That sort of thing.

Louis Gibson: One thing I’d emphasize too is that reentry is never over. It is an ongoing process. I tell people to treat reentry like they’d treat substance abuse. You never fully recover. It’s always one day at a time. One week at a time. One month at a time. We see guys come home and get the services that they need — Medicaid, phone, bank account, driver’s license — and they get that initial footing, and for six months to a year they’re doing good. But at some point they start encountering bumps in the road. They start running into life’s problems. Maybe your record stops you from being able to do things. Maybe your addiction comes back. You pick up old habits, or find relationships with bad influences. Maybe you start to repeat. When you’ve been inside for 20 or 30 years, it’s too easy to slip back into that lifestyle.

We know the warning signs. So we try to educate their families about these things. Tell them what to look out for. But mostly tell them that these guys are going to need ongoing support.

Personally, I try to stay in contact with our clients who get out even over the long term. I’m in contact with over 300 men and women at this point. And those are just the ones I proactively reach out to. My phone is also always open to anyone else who needs me.

And all of this still applies to us, too. I’ve been home almost seven years now, and I’ve been going to support group meetings the whole time. I still go, because I need them. You don’t ever recover completely.

Prison also exacts a lot of physical harm. I’ve talked to and written about guys who discovered after getting out that they had serious medical conditions that were never diagnosed in prison. How have you all managed your health since you got out?

Louis Gibson: After I got on Medicaid, I went to get my first checkup. I had always worked out inside the prison. I thought I took care of myself. When I went to get the checkup, they were like, you feeling okay? I said, yeah, I’m good. And the nurse said are you sure? And I said yeah, I feel good, you know? And she said, well, the doctor’s going to come in and talk to you.

The doctor came in and said my blood pressure was way too high. Way too high. I couldn’t understand it. I wasn't eating red meat. Don’t eat pork. And I said okay, so, what do you want me to do, thinking they were going to suggest lifestyle changes. And he said, your blood pressure is too high for us to let you leave. We can’t let you leave until it’s under control.

So yeah, that was a shock to me. I had been home for six months, and I had dangerously high blood pressure. They said it’s probably been that way for years. I never knew.

Robert Jones: They told me I was borderline for diabetes, which made me dramatically change my diet. I had high blood pressure too, but I knew about that when I was inside. But I’ve been able to maintain it and weed myself off of medication by watching what I eat.

Terry Pierce: I was shocked to find out that I didn’t have anything wrong with me.

[All laugh]

But seriously, I was raised by a diabetic. My mom was sticking herself when I was a child. I thought I’d at least have that. I’m a veteran, so I went to the VA hospital and had them check me out for everything. I thought they were lying to me, so I went to another doctor too. I had so many tubes of blood drawn from me when I got out.

And somehow, I’m good!

Robert Jones: You don’t get real medical care in prison. So Terry’s excellent health aside, I think a lot of people are surprised to find out how unhealthy they are when they get out. I’ve personally known quite a few people with undiagnosed conditions. Some learned they have cancer. A few of them have died and probably would have lived with proper care in prison.

Everett Offay: But I think the biggest thing we see from guys coming out of prison is with mental health. It’s the trauma, the unchecked trauma. You do any real time inside of prison, you’re going to be traumatized. Hell, we grew up traumatized. A lot of us grew up in traumatizing environments. And when you then go to prison for over two decades, you become institutionalized. You learn how to get by, how to survive. And those survival skills become your life. They become a part of who you are.

Now all of the sudden you’re back in society. And all those norms you had to learn in prison are now abnormal. In your mind, all your norms are now abnormal. The big things, the little things, everything in between.

It’s the way you interact with people. That way you learned how not to trust anyone? You’ve got to unlearn that, now. Everything you learned you now have to unlearn. And if you don’t understand that — if you can’t admit that you’ve been traumatized — your life outside is going to be lopsided. Because you’re going to need people to help you.

So we try to help these guys understand that. We try to help their families understand that too — that the way this person interacted with people in prison inside is very different than the we interact with each other out here. That’s a big thing both our clients and their families have to learn.

I tell the families, hey, I know you love him. There ain’t no doubt in my mind that you love him. But I promise you, you don’t know how to deal with this person.

For example, in prison everything is decided for you. You get three meals a day. But it isn’t just that what you eat is decided for you, the amount of food you eat is also decided for you. So when you get home, you want to eat all the food in the house, because eating more food was never an option for you before.

In prison, you didn’t have to worry about the water bill or the light bill. Now you come home and these are things you have to start thinking about. So you can’t leave the lights on all day, because you have to pay for that. These are now your responsibilities. In prison, you wore the same thing. Now you can wear whatever you want. But there’s also nobody washing your clothes for you.

Some of these guys went in before cell phones were a thing. So many guys come home and don’t know what to do. Everything is electronic now. You need an email address for this. You’ve got to e-sign this. You need a password for this, you need a code for that. You have to know your Social Security number.

You didn’t have to know any of that in prison. The only number these brothers had to know for 20 years was the code for their locker box.

So part of the mental health aspect of it is just adjusting to everything in your world changing all at once. It can be overwhelming. That’s one of the biggest things.

I wanted to ask you about that. There’s an unfortunate stigma sometimes attached to mental illness. It’s getting better, but it can still be difficult for people to seek help. That seems especially true for men, and I’m guessing it’s especially true for men who have been incarcerated.

Everett Offray: I go to therapy once a week. Every Tuesday.

Is that something you try to encourage for your clients?

Everett Offray: Yep. Absolutely.

Robert Jones: Mm hmm.

Louis Gibson: Yes. Definitely.

Robert Jones: When I first got out, I didn’t think I needed it. I thought, I’m just going to educate myself on everything. I didn’t need the stigma that comes with going to therapy. But it was a peer mentor who persuaded me to try it. And that’s how I discovered how helpful therapy can be.

That’s why I think peer mentorship is so important. You can enroll in all the services. You can get your driver’s license. You can do this and that, all those things that make you seem like a regular person. But having someone guide you through the process who has been there is so important. Because you have to reckon with that transition you’re making. Getting a driver’s license doesn’t mean you’re no longer in that prison mindset. It’s just a piece of plastic. You need someone who has been there, who can talk to you and say look, I see the signs, and you aren’t there yet. Here are the things you still need to do to succeed. And addressing your mental health is a really big one of those things.

Terry Pierce: Yep. So true.

Robert Jones: And having someone who’s never been through it tell you that isn’t going to do it for a lot of guys, no matter how sincere they are. A lot of guys are only going to listen to someone who’s been through it. Someone who has also been inside. Someone who can say, “You may think you’re all right, but you’re not.”

My therapist used to treat war veterans for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. He told me that when he eventually started seeing formerly incarcerated people, he was seeing the same symptoms. And that makes sense, you know? The military breaks you down, strips you of your identity, and then turns you into someone else. That’s what prison does. You to go war in the military and you see people die. We saw people die all the time in prison. In the military they have rules that govern every minute of their lives. We had that too.

Louis Gibson: With therapy, though, it wasn’t just the stigma from other prisoners. If you sought therapy, it was held against you by the prison officials. It was like you were admitting you were unstable. So getting therapy or mental health treatment meant you couldn’t get certain positions inside the prison. You couldn’t be a trustee. You couldn’t get into programs.

So that stigma gets ingrained in you. If go see a psychiatrist, is that going to make it harder for me to get a job? Will I be able to rent an apartment? Who’s going to know that I’m seeing a therapist?

It’s something I recognized when I first come home, and that I had to overcome. But all of us at this table know that it’s just a stigma. That’s all it is. We know getting help improves your life. So we can tell these guys: Look, we got treatment. And we still do therapy.

Therapy can be expensive. Is that also a barrier to these guys getting treatment?

Louis Gibson: Most don’t accept Medicaid, but with some of the reentry programs, it’s like $10 a session. For some guys, I’ll even pay for them to go. If you don’t like it, fine, don't go anymore. But at least try it out on me. See if it helps. And for most of them, it helps.

But I’ll just say again that most of these guys don’t want to hear any of this coming from an attorney. They don’t want to hear it coming from a social worker. If they’re going to do it, it’s because someone who also did time is telling them this is something that will help them.

“After about 10 years or so, it starts to hit you. This is the only thing left in my life. The rest of my life is going to be me working in a cotton field, with a guy riding behind me holding a gun, spitting tobacco at my feet.”

There’s also a stigma around public defenders — that they’re ineffective, overworked, just a cog in the system. Part of your job is to build trust between your clients and these attorneys. How do you go about doing that?

Terry Pierce: I use myself as an example. I tell them about the representation I had in 1980 versus what they have today. My attorney never came to talk to me. Not once. He hadn’t been practicing law for three years when he took on my case, a murder case. He had a senior counsel assisting him, but that was just for show. That senior counsel didn’t open his mouth once through my entire trial. I acted in self-defense, so it should have taken some time to try my case, for the jury to consider the evidence. My trial took six hours total. That’s picking a jury, deliberation, everything. It all took six hours.

That’s one of the really perverse things about that era. Indigent cases were paid with a flat fee, and usually a pretty paltry one. So experienced attorneys didn’t want the hard, time-consuming cases. So the most serious charges — rape, murder, even death penalty cases — tended to go to people just out of law school because they wanted the trial experience.

Terry Pierce: I was so angry about that for so long. But once I became a jailhouse lawyer I started to learn what effective representation looks like. I learned that in the 1980s they just didn’t have the resources. I’ve grown to learn that it really wasn’t the attorney’s fault. He did the best he could for very little pay. He never met with me because he just couldn’t. He had too many other cases.

But this is what I tell my clients. You’re meeting with your attorney regularly. You’re meeting with a social worker. An investigator. You’re meeting with me. Maybe you’re tired of all these meetings. Maybe you’re tired of us bothering you. But this is what good representation looks like. Even if you had all the money to hire a private attorney, you aren’t going to get better than this. These folks are dedicated. They don’t go into this work for the money. They’re believers.

Robert Jones: I still hear people say, “I don’t want no public pretender. Get him outta’ here.” I tell them, you aren’t just getting a lawyer. You’re also getting investigators. You’re getting a client advocate. A social worker. Paralegals. A peer mentor. You’re getting a whole team of people working for you. Doesn’t even matter if you did it or not. They’re still going to work for you — not just on your charges, but for your betterment. Go ahead and pool all your family’s money and waste it on a private lawyer if you want. But you won’t be getting all that anywhere else. This is the best you’re going to get.

Terry Pierce: Clients used to say, “Oh, y’all work for the state.” And I understand where they’re coming from. I was on that side of it. I experienced that. And so I tell them, you know, you’d be right if this was still 1980. But I say, think about it this way: I got out my bed at six o’clock this morning to come visit you in jail today. Would I do that if I was working for the system? No. I’d be doing what my attorneys did to me. You’d never see me here. I come here and bother you because I work for you. We work for you.

Robert Jones: We have to fight that stigma in the community too. When I came home from prison, got a job in this office, and started dressing in a suit to go to court, people would see me and say, “How can you sell us out like that after what they did to you? How can you work for the system?”

So we had to start addressing that. We had to start looking at how the public defender is seen in the community. So we started restructuring the office. One of the roles I now have is community organizer and director of community outreach. We started partnering with grassroots organizations to host events around the city. We go out and talk to folks, and they get to know us, and word spreads and that starts to build the trust. There’s still a lot of mistrust. It’s still there. You still hear it. But it’s a whisper now. But seven or eight years ago, it was a roar.

Terry Pierce: Sometimes you can build trust by talking about what else is going on their life. Like, you say you got two kids out here? Well then you’re going to have to take some responsibility. Yeah, any attorney can help you fight these charges. But we’re going to get you counseling and treatment for substance abuse. We’re going to help you with life skills. Job training. We know the system doesn’t rehabilitate. It just cycles you in and out. We’re here to stop that cycle. We’re trying to treat the whole person, not just that one part of you that was accused of a crime.

Here again, I can tell clients about my own life. How are you going to help raise those kids if you ain’t ready, right? I tell them I didn’t have services like this when I was arrested. And to be honest, it was probably was a blessing in disguise to be away from my two children all those years. My daughter just turned 50 years old. And she’s doing great. The way I was living, if I would've stayed around I wouldn’t have been a good influence on her. I wasn’t ready. I didn’t have someone to help me develop those life skills.

Hold on. You have a 50-year-old daughter? How old are you?

Terry Pierce: I’ll be 68 in September.

Robert Jones: Good for you, son.

Terry Pierce: Black don’t crack.

[Lots of laughs.]

You also help clients and their families prepare for and adjust to prison after they’ve been convicted. That seems like an especially difficult part of the job.

Louis Gibson: I just had that talk with one of my clients. He was so glad I came over there to see him, just knowing that I was there. He just wanted to know what are my next steps? What do I need to do?

But the really important part of that preparation is talking to the families. You have to give them hope. Because it’s so much harder inside without that support from your family. I try to tell them, okay, now that the worst has happened let’s start focusing on the next steps. Let’s get to work on making this situation as better as we can.

When you’re serving a life sentence, you’re told that you’re going to die inside the prison. It’s so hard to have hope when that’s what you’re hearing. So I try to tell them that I was right there. That’s what they told me too. I had a life sentence and they told me I was going to die in prison. And so just my being here, next to you, telling you all of this, that’s a reason for hope. I thought I’d die in prison. Now I’m out, and I have a job where one of my responsibilities is to give you hope. And that is reason for hope. None of us knows what’s going to happen in 10 or 20 years.

Robert Jones: I just was telling that to a guy the other day. But on the other side of it, we also get the chance to work with the lawyers to provide these guys with information based on our own experience that can help them make informed decisions — decisions like, should I accept an offer to avoid a long sentence?

We’re in a place where we can say, look man, based on these facts and this evidence here, this is what’s probably going to happen. I’m not trying to be the jury, but I’m telling you this is our experience. You have to make your own choice, but here’s what we can tell you is likely to happen. We can help them make a more informed decision so they don’t risk a trial and a harsher sentence if they’re convicted.

Their attorneys will tell them the same thing, but sometimes they can be technical about things. I can give it to them raw: if you go to trial and you’re convicted, this is what’s going to happen to you.

So when a client has already been convicted, you help them prepare for that adjustment to prison. But when they can’t see the facts in front of them, sometimes you have to tell them what 10 or 20 years is going to do them. Like how very night when you’re trying to sleep, you’re going to hear guys hollering. You’re going to wake up yourself many nights, wishing you hadn’t taken that deal.

You’re going to lose all your hair. Most guys you see in prison who have been there a long time, the vast majority of them are baldheaded. I don’t know if it’s the stress or what, but we lose our hair. And because the dental care is so bad, after they lose their hair a lot of guys start to lose their teeth. So you need to think about all of that when you say you want to go to trial.

Terry Pierce: Oh man, amen. I'm a living witness to that. I committed the act I was charged for, but I just couldn’t establish that I did it in self-defense. They tell you it’s the state’s burden to prove your guilt, but when you’re arguing self-defense the burden is on you. So in my case, they offered me a deal that would have had me serve 21 years. What did me in was that I thought I had a 50/50 chance of winning at trial. I thought, either they convict or they acquit, right? So I have a 50/50 chance of going free. I was so gullible. I wish there had been someone there to tell me when I got arrested that with the system we had then, a 50/50 chance was really no chance at all. So I served 41 years instead.

Everett Offray: I think it’s about helping them make an informed decision. Most everybody who commits a crime doesn’t really understand how the system works. The advantage that we have is that by us doing time, we understand a whole bunch about how it works for real. So that’s what I try to do. I’m going to try to equip you with enough information that you can make an informed decision.

Once I explain to you how it all works in real terms, then you can have a better conversation with your attorney. Because people make these important decisions that affect the rest of their lives based on what they hear on the street or what they see on TV. I’m going to bring it to you straight: This your future if you take this option. And her’s what your future could be if you take the other option.

Sometimes it’s hard for people to see beyond that possibility that they could get acquitted. They can’t comprehend spending the next five years in prison. So they’ll roll the dice on a really small chance of an acquittal. I try to say man, the state has a lot of evidence. And if you’re convicted, the day’s going to come when you wake up in year six of your 20-year sentence, and you’re going to be devastated.

So I try to give them that perspective. I know what you’re hearing right now is hard, but it’s way softer than what it could be.

Nobody did that for us. We didn’t know. We didn’t understand that we’d be sentenced to die in prison. I was 18 years old. Some were 16 years old. We were kids. They say the mind doesn’t fully develop until you're 25. So at 18, how am I making an informed decision? I’m charged with first-degree murder. I’m in a panic. All I want to do is go home. And the only thing that offers even the slightest bit of hope for me going home is a jury trial.

I was 18 and facing the death penalty and my lawyer never came to see me when I was in prison. Not once. The only time I ever saw her was in court. How was I supposed to make an informed decision that was going to affect the rest of my life? How can you talk to your client for real when your only conversations are in court, in front of a bunch of other people?

When you’re young, you just don’t understand what it means to lose your entire life to prison. It wasn’t until we matured that we started to understand. Angola is a literal plantation, you know? So after about 10 years or so, it starts to hit you. This is the only thing left in my life. The rest of my life is going to be me working in a cotton field, with a guy riding behind me holding a gun, spitting tobacco at my feet.

So that’s my thing. That’s my mission. I try to talk real to everybody, in every situation, no matter who it is. I say this is what your life is going to be like. And it isn’t just that your days are going to be like that. It’s that all your future days are going to be like that. You’ll get to the point where you won’t even be able to imagine anything different. So if you want to take a chance on a jury, that’s your right. But I’m going to make sure that you understand the repercussions of that.

“My favorite TV show is ‘Gilligan’s Island. You know why? Because they’re always trying to get off that goddamned island. Nothing they did ever worked. Every day, they wake up and they realize they’re still there. But they never stop trying to get home.”

You were all at Angola, right?

[They all nod.]

I have to ask, what’s with the prison rodeo thing? It seems so exploitative. But I also hear that for some prisoners it’s at least a distraction from the monotony of life inside. What do Angola prisoners really think of it?

Robert Jones: It’s a spectacle. It’s Roman Coliseum stuff, where all the caesars would entertain the masses by having them sit around and watch convicts fight lions. It’s the same premise, right?

But for a lot of guys, after you’ve served a long time, you start to lose touch with your family. You have nothing else going for you. You have no one putting money in your prison account. So maybe you make some things for the craft fair that they do with the rodeo. And if you can’t do crafts, then your only option is to participate in the rodeo, or sit down for the convict poker.*

[*Note: You really have to read about “convict poker” to understand how deranged it is.]

Michael Banford: It’s foolishness.

Robert Jones: The prison makes a lot of money. They make half a million dollars a weekend off that stuff. And then they take 30-40 percent of the profits from the crafts. It’s slavery all over again. It’s nuts, man. Such a spectacle. Nothing good about it. But people still go. They go to see the spectacle, fraternize with the prisoners, visit with their loved ones. Or they go to get good deals on handcrafted stuff.

Everett Offay: Ain’t nothing good about it.

A few years ago, I sat in on a really intense attorney meeting with a client — with the client’s permission of course. This guy had been in prison for 10 or 15 years, and had some clout and respect inside. when he got out, and he didn’t have that same clout and respect. In prison, his visits with his wife and kids were these happy occasions because he hadn’t seen them in a week.

When he got out, he’s living with them, and dealing with all the domestic strife that comes with that. He ends up holding up a fast food restaurant just because he wants to go back. So at this meeting, the judge had offered to suspend his sentence if he’d do in-patient mental health and substance abuse treatment. So the meeting was him attorney trying to convince him to do treatment so he doesn’t have to go to prison for 15 years. And he’s saying he’d rather just go back to prison.

I guess I’m just wondering how common that is. How many of your clients just get used to being incarcerated to the point where they can’t imagine anything else?

Robert Jones: It’s more common than you’d think. I had a client like that recently. One of his attorneys is a professor at a local college here. He had done 40 years and was up for parole. So I had put a mitigation packet for him. He got paroled. But when it came time for him to get out, he refused to go. All he knew was prison. He just refused to leave. We literally had to beg him to leave.

A few months later I was walking out of the courthouse and I saw him in a suit. He was coming from, he was walking around, he was getting off the bus, going to his job. He said, “Man, I knew I’d run into you one of these days at this stop, and I’ve been thinking about what I’d tell you. I love it out here, bro. I’m glad you had that talk with me, bro. I didn’t want to listen to nobody else.” And I felt good about that. But man, I had to beg him. I had to beg him to leave.

That was a client that just came right out and said it — who just said he didn’t want to leave. But you see it indirectly too. You see guys who won’t say they’d rather be in prison, but who show it in their actions when they get out.

Louis Gibson: We had two guys like that with the Resentencing Unit. The only thing they had to do to get out was complete counseling. And they refused to meet with counselors. So we had to try to talk to them about it. We had to tell them, look, your sentence was illegal. You don’t deserve to be here. It’s time to come home. They wouldn’t come right out and say they didn’t want to leave, but they wouldn’t do this pretty easy thing that would have let them go.

But those guys also had some mental illness. I don’t think I came across anyone in the resentencing project who didn’t come home. But what was really common — what almost all of them experienced — was that it was a lot harder to adjust than they thought it would be.

It was really uncomfortable for them because now they have to make a lot of decisions. You get used to like a certain setting. You get used to the routine. When go to bed, you’ve got somewhere to sleep. You don’t have to worry about what clothes to put on, or what you’re going to eat. And it’s hard for people who have never experienced it to understand, but going from where every decision is made for you for 30 years to having to make decisions for yourself is one of the biggest adjustments. And that’s where some clients say to me, “I’m just so overwhelmed by all of this that I’m ready to go back to prison.”

We can usually talk them down, but that’s a real thing. You get used to that helplessness. And so when you get out, you start thinking you were more comfortable inside the institution.

Terry Pierce: Not to mention that when you’re in that long, a lot of these guys lost everyone. All their family. Everyone they know, they’re all dead or estranged. So they have nothing to come home to. So prison family is the only family they have left. It’s the only familiar thing they have.

“I’m in a position to educate people about the public defender office, but I’m also in a position where I can educate the lawyers about their clients.”

Michael Banford: Let me interject something here. I think we just need to acknowledge this bottomless pit — this abyss that takes your life from you one day at a time. It tests your will. It tests your strength. It steals your emotions and your intellect. It challenges you as an individual to hold on to the things that make you human.

Martin Luther King said that when a man loses hope, he dies. Mentally, physically, emotionally, spiritually — he dies. When they first get to prison, everybody has this hope that one day they’ll come home. You have hope for the constitutional claims or structural claims that you’re still fighting in court. And maybe you hear about a reversal here and there in other cases — just enough to keep you hoping. But the statistics say 85 percent of lifers will die in prison. So you spend decades navigating this beast that is slowly draining you of that limited reserve of hope you came in with.

I think that’s what you’re seeing with these guys who don’t want to leave. It’s only after you’re utterly drained of hope that you start to make your peace with the fact that where you are now is all you’ll ever be. And once you adopt that mindset, you start to identify as a prisoner. Being a prisoner is all you are. Even in your best dreams you’re still behind that fence. Everything you do, everything you think, everything you say is prison.

That’s why it’s so important to have a support base. It’s why I always try to emphasize to the families that they have to stay in touch with these guys. Visit them if they can. These guys need to know that if they ever get out, their non-prison identity is outside that fence. Because when you give up that idea, you die as a person. You’re just a body in a prison.

Robert Jones: I used to stay up at night and look out over the dorm at all the guys sleeping. All those bodies sleeping. Bear with me now because I’m going somewhere with this.

When I started working at the prison library and learning the law, I learned that almost all of these guys still had legal challenges they could make. Almost all of them would have lost because of that phrase you see over and over again: procedurally barred. So most of them give up because they figure they had no chance of winning.

But like Michael said, when you stop fighting it means you’ve lost hope. And when you lose hope you die.

So I’d look out over all those bodies at night, and to me the dorm just started to look like one big morgue. It was only missing the toe tags. All these guys had given up. They had no hope. And so that identity, that person Michael says was waiting for them on the outside, that person was dead. They still might walk and talk and eat. But they’re dead. They all just looked dead to me.

Terry Pierce: It’s so true. You die more than once in prison.

Robert Jones: You know I used to get into arguments with guys over the TV because once I was established inside I got to pick what to watch. And you know what my favorite TV show was? You know what I made everybody watch?

'Gilligan’s Island.’

[Lots of laughs]

You can laugh. You can laugh all you want. But I loved that show. You know why? Because they’re always trying to get off that goddamned island. Nothing they did ever worked. Every day, they wake up and they realize they’re still there. But they never stop trying to get home.

Jesus. That’s really poignant. But also dark!

Robert Jones: But it isn’t dark, because they never gave up! They wrote letters and put them in bottles. They built a radio out of coconuts and shit. They made rafts. They never stopped trying. And every time you thought they had tried everything, they’d come up with something even crazier.

And guess what?

They got off that fucking island!*

[*Note: I was curious about this, so I did some research. And this metaphor really takes on a life of its own. In the first made-for-TV reunion movie, the castaways do finally get off the island. But they then inexplicably get together for a reunion *on a boat*. That boat also encounters bad weather, wrecks, and somehow leaves them stranded on the same deserted island. In the second made-for-TV movie, they’re again rescued, but they have a hard time adjusting to society, so they return to the island and open a resort. In the final made-for-TV movie — and this is where the metaphor begins to fall apart — an evil millionaire tries to take over the resort. At about the same time, the Harlem Globetrotters have to make an emergency airplane landing on the island. The castaways and the millionaire decide to settle the dispute over the resort with a basketball game between the Globetrotters and a team of robots owned by the evil millionaire. The Globetrotters win.]

You’ve worked as jailhouse lawyers, so you know how important the post-conviction stage of a case can be. This tends to be when you learn about potentially exculpatory evidence. But it’s also when it’s hardest to get a court to revisit your case. It’s when you get those procedural bars Robert mentioned. So I’m curious what you make of Jeff Landry, the new governor in Louisiana, who wants to both make even more difficult to get back into court post-conviction, and wants to cut funding to the nonprofit offices who have been providing post-conviction representation to indigent prisoners.

Robert Jones: When we were jailhouse lawyers, offender counsel, whatever you want to call it, the work we did helped spin off these non-profit organizations. And some of those organizations then worked to change the laws. When I got out of prison, me and other formerly incarcerated people hit the ground running. We started testifying before the legislature, and helping elect people who would implement reforms.

And it was getting better. It was progressing. We got our voting rights back. We got Ban the Box passed. We got the non-unanimous juries banned. So what Landry is doing is personal for me. After 23 years in prison for a crime I did not commit, I took out time away from my family and traveled the state organizing and advocating to make sure what happened to me didn’t happen to anyone else.

That’s 23 years of hardship, and then several more years of tirelessly advocating. And Landry undid all of that progress in 30 days.

Terry Pierce: He took good time away. So guys getting arrested now, they can’t get good time. Took parole away. Just killing all the hope. When you can get credit for good behavior, when you have hope for parole, you can still see yourself on the outside. There’s incentive for you to hold on to that person you were. To not become this animal they want you to be. They don’t get this. They don’t get how taking away that hope is going to affect the prison.

Robert Jones: And now they’re sending juveniles to the adult prison again. They didn’t learn anything. All that suffering, and they didn’t learn a thing.

It’s horrible. We made changes that resulted in a lot of guys getting out. Hundreds of guys. And they haven’t recidivated. They’re doing really well. But instead of continuing with what was working, they go back to just killing any chance for these guys to hope.

But you know what? Bad times don’t last forever. I went to prison in the early 90s, and for more than a decade I didn’t see a single person go home.

Michael Banford: I saw one or two at most.

Robert Jones: But after 15 or 20 years, we started getting the laws changed. People started getting out. And in the last six years, I’ve seen hundreds. So what we’re seeing right now, I have hope that will pass too.

Is there anything I haven’t asked you that you want to talk about?

Michael Banford: I just want to emphasize this again: It’s critically important for families to be there for their loved ones. We know so many dudes in prison with no family support. When they don’t have that, it stunts their growth and development. That potential that we know that’s in them is staid because they don’t have the love we all need. When you don’t have that human connection, your humanity shrivels up.

I’m a great example. I didn’t have that family support. I didn’t see my people for Christmas. I didn’t get nothing for birthdays. I didn’t see nobody on Easter. In my 29 years, three months, and 17 days, I probably saw my mama 10 times.

Now I made it out of prison. But I only made it out because I met these guys here working in the library. I had these dudes helping me and supporting me. These guys reached out to me, and ushered me to do good, and then greater, and then excellent things. I was lucky. But most people didn’t have that.

Robert Jones: “Out of sight, out of mind” is a reality. You have to make a real effort to stay concerned about somebody that you don't see every day. When your loved one is prison, maybe you don’t talk to that person for a few days. And then it’s weeks. And then months. And then it’s years. All that time is passing. But you’re not thinking about it because you’re facing bills and doctor appointments and children crying. It’s just so easy to lose people. I’m out and I have people I love that I don’t talk to often enough. We get distracted. You add prison to that, and people just fall out of your life.

Robert Jones: Exactly. If you can’t visit, call. And if you can't call, write. It doesn’t take a lot to help them keep their sense of identity. When I was in prison, stamps were 29 cents. When I went to the commissary, instead of buying chips I’d buy a book of stamps. I was desperate to keep those lines of communication open. That’s how I started building myself a team. I had people writing me, sending me cards, sending me a few coins here and there. It’s hard to be hopeless when you have people hoping for you.

But they make it harder to have hope now. For your family to visit you, they may have to drive three hours to get there and three hours to get back. So that’s six hours for someone who might be working a couple jobs and have kids or grandkids to take care of. And then you get something to eat while you’re there. You leave you a couple of hundred dollars in your loved one’s account. Those visits get expensive.

Terry Pierce: Or you take a few hours driving there and find out there’s an unscheduled lockdown. Or your wife or mom wore a bra with an underwire, which they don’t allow.

Robert Jones: So then you have to go buy one of those $50 t-shirts just to get in. It's a whole lot for a person making less than $30,000 a year. And over time it just gets to be too much for people. It’s like, I’m accepting all your calls, coming to see you all the time, sending you money, getting you something to eat. Every time I come, it’s three or four hundred dollars, and I just ain’t got that in my budget anymore.

So then you stop visiting. But phone calls are now $7 a call. A lot of prisons are doing away with physical mail. You can only send email, and they charge for that. So you stop communicating that way, too. And we’d see it. You’d see guys slowly dying as they fell out of people’s lives.

Michael Banford: It’s all about killing off that hope.

That’s why one of the most important thing we can do is help the families keep these guys in their lives.

Radley, you are amazing. Thank you for giving these guys a voice. It makes me ashamed to be an American to read this. As a White, male boomer I can't imagine what they've endured. I know I couldn't stand being locked up. I would either stick a gun in my ear or commit suicide by cop. That these guys endured years in a shit hole like Angola is beyond my comprehension.

Wow, this is so powerful! You encapsulated so much of the pain and loss spending decades incarcerated. And you managed to convey what is needed to help these people rebuild their lives.

Thank you!!!