The "broligarch" threat to criminal justice reform

Crime rates are falling, and criminal justice reform remains urgent and popular. But led by Elon Musk, a new generation of Republican megadonors are spending millions to kill it.

The 2024 election was a complicated one for criminal justice reform. The narrative now emerging is that voters soundly rejected reform. That narrative is driven in large part by Trump winning on a tough-on-crime (and lying-about-crime) agenda, along with some high-profile setbacks in California, including losses by two progressive prosecutors and voter rejection of reform on a couple ballot initiatives.

But that narrative also isn’t quite right. Reform fared well in much of the country. A more accurate narrative is that reform won in places where voters were left to choose based on their own experiences, and it lost in places where a new generation of high-dollar Republican donors spent heavily to spread misinformation and stoke irrational fear about crime.

Crime was an election issue that in some ways paralleled the economy. On both fronts Democrats and the Biden administration inherited a mess created by the pandemic and the Trump administration’s exacerbation of its effects. On both fronts, Democrats appear to have been punished at the polls because of the lag between what’s actually happening on the ground and voters’ perception of what’s happening (crime has been dropping, and the economy has recovered). Finally, on both fronts, the effects of that lag were amplified by poor messaging from Democrats and dishonest fearmongering by these neophyte Republican donors — led by tech figures like Musk, David Sacks, and Mark Andreessen, who have been red-pilled in the years since the pandemic.

We now know that violent crime spiked during the pandemic. And because the spike happened at about the same time as some of the reforms spurred by the George Floyd protests, there’s been a concentrated effort on the right to blame the spike on those reforms. There is at least some persuasive evidence that that the protests themselves contributed to the crime spike. The mechanism by which that happened is less clear — theories (which are often disputed) include “de-policing” by law enforcement officers angered by criticism and accountability measures, broken trust between police and the communities they serve, or just the general division and chaos stemming from the pandemic, Trump administration, and civil unrest over racial injustice.

There is very little evidence that criminal justice reforms or progressive prosecutors are responsible for the spike in violent crime. Multiple studies have found no correlation between reform and crime rates at all, and as far as I know just one study claimed to find a correlation between progressive prosecutors and a slight uptick property crime — but no link to violent crime.

But the more obvious reason to doubt any link is that between 2020 and roughly 2022 violent crime also went up everywhere, including in jurisdictions with traditional, law-and-order prosecutors. It then went on a steep, nationwide decline in 2022. That, too, has been a nationwide trend, including in jurisdictions that passed and sustained reforms, as well as those that retained progressive prosecutors.

But the narrative appears to be immune to data. The most high-profile loss last week in Los Angeles, where voters ousted district attorney George Gascón, one of the more well-known names in the progressive prosecutor movement. Gascón faced a revolt the moment he took office, as the prosecutors’ union went to court to get an injunction barring him from implementing reforms — reforms clearly supported by voters at the time — by arguing that they violated the rights of prosecutors. (That’s a hell of a sentence to write.) And they won.

Gascón then faced over two dozen more lawsuits from holdover prosecutors. They accused him of retaliation for publicly criticizing him, and of interfering with their cases by imposing the policies he was elected to implement. I can’t speak to the merit of specific accusations, but as someone who has been watching this stuff for 20 years, I can say that a reform-minded line prosecutor who publicly criticized a traditional DA the way these prosecutors went after Gascón would be fired in a heartbeat. L.A. prosecutors seem to think their “right” to implement carceral policies supersedes the will of the people they serve. And unfortunately, the courts seemed to agree, as some of these prosecutors won six and seven-figure awards. Still, Gascón survived two recall attempts before finally losing last week.

California voters also passed a ballot initiative to increase penalties for some drug crimes, and to allow felony charges for repeat low level theft offenders — a response to the widely-distributed myth that a 2014 initiative had effectively “legalized” shoplifting in the state. The state’s voters even rejected a ban on forced labor of incarcerated people.

A case study in Oakland

There is one California result from last week that I think most epitomizes the flaws of the anti-reform narrative. It wasn’t an election between two candidates, but a recall vote for Alameda County, California (Oakland), District Attorney Pamela Price.

The measure passed by 30 points. Voters in Oakland also recalled the city’s mayor, Sheng Thao, by a similar margin. Both officials were flawed, and both recall efforts were funded by a group of wealthy hedge fund managers, tech elites, and real estate investors who claimed to be concerned about crime. The recalls have been framed in the media as a liberal city rejecting criminal justice reform. I don’t think we can really say that.

Price, a civil rights attorney, first ran for Alameda County DA in 2018. She lost to an establishment incumbent, Nancy O’Malley. When O’Malley retired in 2022, Price ran again on on a slate of progressive reforms. She pledged not to seek the death penalty, proposed more diversion programs, said she’d stop charging minors as adults, vowed to establish a conviction integrity unit, and promised more scrutiny of and accountability for police abuse. She defeated an establishment candidate from O’Malley’s office, and became the first black woman DA in the county’s 176-year history. Last week, she became the first DA in Alameda County history to be recalled.

Upon taking office, Price emphasized police reform in particular, and there are good reasons why that resonated with voters in 2022. The Oakland Police Department has a long and sordid history of abuse and corruption dating back decades, and has been under a federal consent degree since 2003, longer than any department in the country. Alameda County leads the Bay area in annual settlements for police abuse. Despite that history, over her 14 years in office, O’Malley brought charges against police officers for an in-custody death just a single time. In one particularly egregious case, O’Malley took a $10,000 campaign contribution from a police union while investigating the fatal shooting of a pregnant teenager by officers who were members of that union — one of whom was the union’s president at the time. She cleared the officers of wrongdoing.

Price immediately reopened several police abuse cases. One of those was the terribly sad death of Mario Gonzalez, a case I’ve previously written about here. O’Malley declined to prosecute the officers for reasons that I argued weren’t supported by the evidence. The county’s subsequent $11 million settlement with Gonzalez’s family — one of the largest in state history — also suggests that officials knew that the officers who killed him were in the wrong.

Price opened her own investigation, and ultimately charged the officers with involuntary manslaughter. As you might expect — and as has happened elsewhere — this put Price squarely in the crosshairs of the police unions.

The first public event calling for Price’s recall occurred just three months after she took office. Her critics filed the paperwork for her recall three months later. So just six months into her term, Price faced an official campaign to remove her from office. It takes months just to implement new policies, particularly when those policies are a fundamental departure from that office’s culture and history.

The speed with which the recall campaign was up and running is good evidence that this wasn’t a sober, good-faith assessment that her reforms weren’t working. Major donors to the recall effort also funded the effort to recall progressive DA Chesa Boudin in San Francisco. They were clearly feeling confident, and it seems safe to say that the plan oust Price was put in motion the moment she won her election.

Recall proponents pointed to rising crime in Oakland. To be clear, those concerns were real and legitimate. As in most places, crime in Oakland spiked in 2020. But the city also saw a much steeper spike than nearby cities like San Jose or San Francisco. Crime also continued to get worse in Oakland in 2022, even as it leveled off in those other Bay Area cities.

Here’s the problem: That disproportionate-even-for-2020 crime surge in Oakland began under O’Malley, Price’s predecessor, a conventional prosecutor with a conventional approach to crime. When voters elected Price in the fall of 2022, they were rejecting that conventional approach to crime. They clearly felt it wasn’t working. And with good reason.

Price’s critics then used the same roadmap used against Boudin: Spend massive amounts of money to mislead voters about the chronology of crime rates and reformist policies, isolate sensationalist cases to stoke fear and anger, and weaponize the anti-incumbent advantages afforded by California’s broken recall system.

Here’s a good example: Like many progressive prosecutors, Price opposed the default use of sentencing enhancements for offenses like gang affiliation and gun possession. I happen to think that’s a justifiable policy. Default enhancements can be draconian, discriminatory, and unfair. But when a toddler was killed in the crossfire of a “rolling gang shootout” on the interstate, the boy’s family, recall proponents, and local media preemptively lamented that Price’s policy against enhancements would let the boy’s killers off easy. This was never true. They were always going to be charged with murder. And if convicted, they were always going to get long sentences. The only question was whether they might someday, decades from now, be eligible for parole. But Price’s policy wasn’t to prohibit the use of enhancements. It was to end the use of them by default — it was to review them on a case-by-case basis. And in the end, Price’s office did impose the enhancements. But by then the narrative was set.

Recall proponents also made the familiar claim we see against progressive prosecutors that Price’s refusal to charge certain crimes was emboldening criminals. This claim, too, lacked evidence. During her first year in office, Price charged a higher percentage of people arrested by police than O’Malley had in her last two years in office.

One of the public faces of the recall movement was Carl Chan, head of the Oakland Chinatown Chamber of Commerce. Chan became an activist opposing criminal justice reforms after he was attacked in 2021 in what he said was an anti-Asian hate crime. The perpetrator was never charged. That man then attacked another woman in San Francisco.

But according to the local outlet Oaklandside, it was Price’s predecessor, the traditional O’Malley, who declined to charge Chan’s assailant, in part because the man was apparently having a mental health crisis at the time. Whatever you make of that decision, it’s notable that one of Price’s chief antagonists was moved to activism by a decision made by O’Malley, not Price.

While victims’ rights groups promoted the recall publicly, behind the scenes it was funded by hedge fund managers, police unions, real estate developers, private equity investors, and ex-prosecutors. The top donor by quite a large margin was a hedge fund manager named Philip Drefyuss, who according to local reports donated or loaned at least $600,000 to recall Price. Dreyfuss doesn’t live in Oakland. He lives in Piedmont. He also helped bankroll the recall of Boudin. Between the DA and mayoral recalls and helping to defeat a ballot initiative for ranked choice voting, Drefyuss spent $1.7 million on the 2024 election alone. As of May of this year, the various groups supporting Price’s recall had raised over $3.1 million. Pro-Price groups had raised about $36,000, though by October it was up to around $350,000.

As with Boudin, that massive funding advantage allowed Price’s critics to wage a barrage of ads portraying Oakland as a city under siege, with little to no rebuttal.

The strongest public safety argument against Price is that crime in Oakland did continue to go up in 2023, the year she took office. And it continued to get worse in Oakland even as it dropped in much of the rest of the country.

But there are a number of reasons that arguments fails. First, there are some strange things going on with how the Oakland Police Department tracks and reports crime data. As the data analyst Jeff Asher reported last month, in its report to the FBI for 2023, the department recorded an astronomical increase in aggravated assaults. Stranger still, the entirety of the anomalous increase was concentrated in two months — January and October — not typically months where we see spikes in crime. Oakland typically sees 300-400 aggravated assaults per month. In those two months the department reported 3,000 and 3,500, respectively. The jump was so dramatic that without it, the entire state of California would’ve seen a slight drop in violent crime. With it, the state saw a 3 percent increase. Those anomalous two months even pushed the national violent crime rate up by 1 percent.

Asher suspected the spike was human error, a suspicion later confirmed by Oakland PD officials. But it doesn’t inspire confidence in the department’s credibility, particularly at a time when some police departments have openly mutinied against progressive prosecutors — especially those who have prioritized holding bad cops accountable.

After correcting the errors, the department reported a 21 percent increase in crime in 2023 over 2022. That still isn’t great, especially in a year in which other large cities saw drops.

But again, it was only Price’s first year in office. We’re now 10 months into Price’s second year in office. And by all indications, crime in Oakland is falling.

— Homicides are down 33 percent from last year. (Homicides were also one of a few classes of crime that did actually drop last year.)

— Overall crime is down 37 percent.

— Burglaries are down 55 percent.

— Robberies are down 24 percent.

— Aggravated assault is down 15 percent.

— Nonfatal shootings are down 32 percent.

Last month — just before the recall vote — Oakland had its first month ever without a homicide.

I know what you’re thinking: I’ve just told you there’s reason to mistrust the Oakland PD’s crime data. So how do we know these figures are accurate? Well, we don’t. But homicides are among the easiest and most reliable figures to track. It’s hard to hide a dead body. And homicides in the city are definitely down by about a third over last year. It’s also notable that unlike the previous mistakes, the stats for 2023 are pretty consistent. It seems safe to say that crime is down by quite a bit, even if some individual figures may be off.

I’m skeptical that a DA’s policies — punitive or progressive — have much effect on crime either way. But you certainly can’t look at these figures and argue that Price’s policies have increased crime. The data just don’t support that.

It’s impossible to say for sure whether voters recalled Price because they were misled about crime and her policies. If so, I’m not sure what that would tell us, other than that when you peddle a false narrative unsupported by data, some people will vote on that bad information.

But there are other reasons why Oakland voters have wanted to remove Price from her position. First, as I mentioned, recall proponents lumped Price in with Mayor Thao. They were portrayed as a package deal. Then in June, Thao’s home was raided by the FBI as part of a corruption investigation. From what I’ve read, it isn’t clear if Thao herself is suspected of criminal activity, or if the raid was to collect evidence against other targets. I’ve seen no suggestion that Price is part of that investigation. But it seems likely that for some voters, the taint may have rubbed off on her.

There’s also ongoing tension between the AAPI and black communities in Oakland. Despite reading several articles and speaking to people in the city about the tension, I don’t feel informed enough to have a strong opinion about what’s driving it. But it seems in part due to Thao firing the city’s black police chief over his alleged failure to discipline officers with a history of misconduct. The tension also seems to have spilled over to the city’s NAACP chapter, which has defended the fired chief and taken some surprisingly hardline, law-and-order positions. This, in turn, has attracted criticism from other civil rights leaders.

Price has also had been subjected to a number of allegations about her ethics and competency. This San Jose Mercury News editorial lays out many of them. She appears to have hired a number of people with dubious backgrounds and ethical issues. She apparently hired her boyfriend for a $100K+/year position despite his lack of qualifications. Ex-staffers have alleged that she made discriminatory comments about Asian-Americans, and she apparently barred a journalist from press events because of unflattering coverage. There are allegations that she conspired to violate state open records laws. And though she charged the three officers who killed Mario Gonzalez, a judge threw out the charges against two of them, not on merit, but because Price’s office apparently missed the statute of limitations.

Progressive prosecutors have battled unfair press coverage, mutinies from police departments and legacy staff, high turnover, character assassination, and huge infusions of outside spending to remove them from office. They’re also susceptible to blame for any upticks in crime, and scrutinized in ways traditional prosecutors rarely are. No one ever asks if a DA’s excessively punitive policies are responsible for a surge in crime.

But we should also acknowledge that there have been legitimate issues with some of these prosecutors, including corruption, poor messaging, and incompetence in running a DA’s office. Price is far from the first to face allegations that seem to have some merit. All of these problems have affected traditional prosecutors too. But when a bad messenger champions a good cause, the cause can go down with the messenger.

It doesn’t seem to me like Alameda County resoundingly rejected criminal justice reform. It seems like a highly-motivated group of voters influenced by a huge spending campaign rejected a specific prosecutor — and there are plenty of reasons besides reform that they might have done so.

The bro-ligarchy

Reform also took a major hit in Texas, where recent reformist gains in the state’s judiciary were wiped out in a single night. Prior to last week, Republicans controlled a hair more than half the seats on the state’s mid-level appellate courts (42-40). But after an unprecedented $18 million spending spree by a group of wealthy tech and hedge fund types (Elon Musk personally gave $2 million), Republicans won 31 of the 32 judicial races on the ballot. Those courts are now 75 percent Republican (62-19).

Nearly all the Republican gains in these races were close, with some decided by less than a percentage point. In other words, it took an unprecedented $18 million spending spree to nudge those races just enough for Republicans to win. But these are now the judges who will hear appeals, including criminal appeals, from blue cities like Dallas, Houston, and San Antonio.

There were also two closely watched DA elections in Florida. Over the last two years, Gov. Ron DeSantis has removed two progressive DAs from office, claiming they were “soft on crime” or “failed to enforce the law,” despite no evidence that their policies were harming public safety, and despite a federal court finding that his removal of one of them violated the First Amendment. Both former prosecutors ran to reclaim their old positions, with mixed results.

In Tampa, ousted DA Andrew Warren lost by 5 points to Suzy Lopez, the woman DeSantis appointed replace him.

But in Orlando, former DA Monique Worrell won back her job with 57 percent of the vote. Worrell’s win raises some fascinating (in a bad way!) questions about whether DeSantis could again defy the will of that district’s voters and remove her from office. There seem to be some early indications that he might.

Why did Worrell win while Warren lost? The most obvious reason is the political affiliations of their respective districts. Hillsborough County — where Warren ran — went for Trump. Orlando and Orange County went decisively for Harris.

But here, too, fundraising was also likely a factor. Worrell outraised her opponent, while Warren’s opponent outraised him by about 2-1. Those two factors are also likely related. Donors are more likely to give to candidates they think will win, and because of the demographics Worrell had better odds than Warren.

Outside of Florida, there’s other evidence that the new Republican donors had an outsized influence on the races they targeted. As the Marshall Project points out, progressive prosecutors who weren’t targeted by wealthy right-wing donors fared well last week, winning in Lake County, Illinois; Oakland County, Michigan; and Albany County, New York.

At the federal level, Donald Trump’s victory over Kamala Harris was more substantial — it will likely end up at around 2 percent. But that’s hardly a blowout. Trump is likely to end with just a hair over a majority of the popular vote. This is still an evenly-divided country.

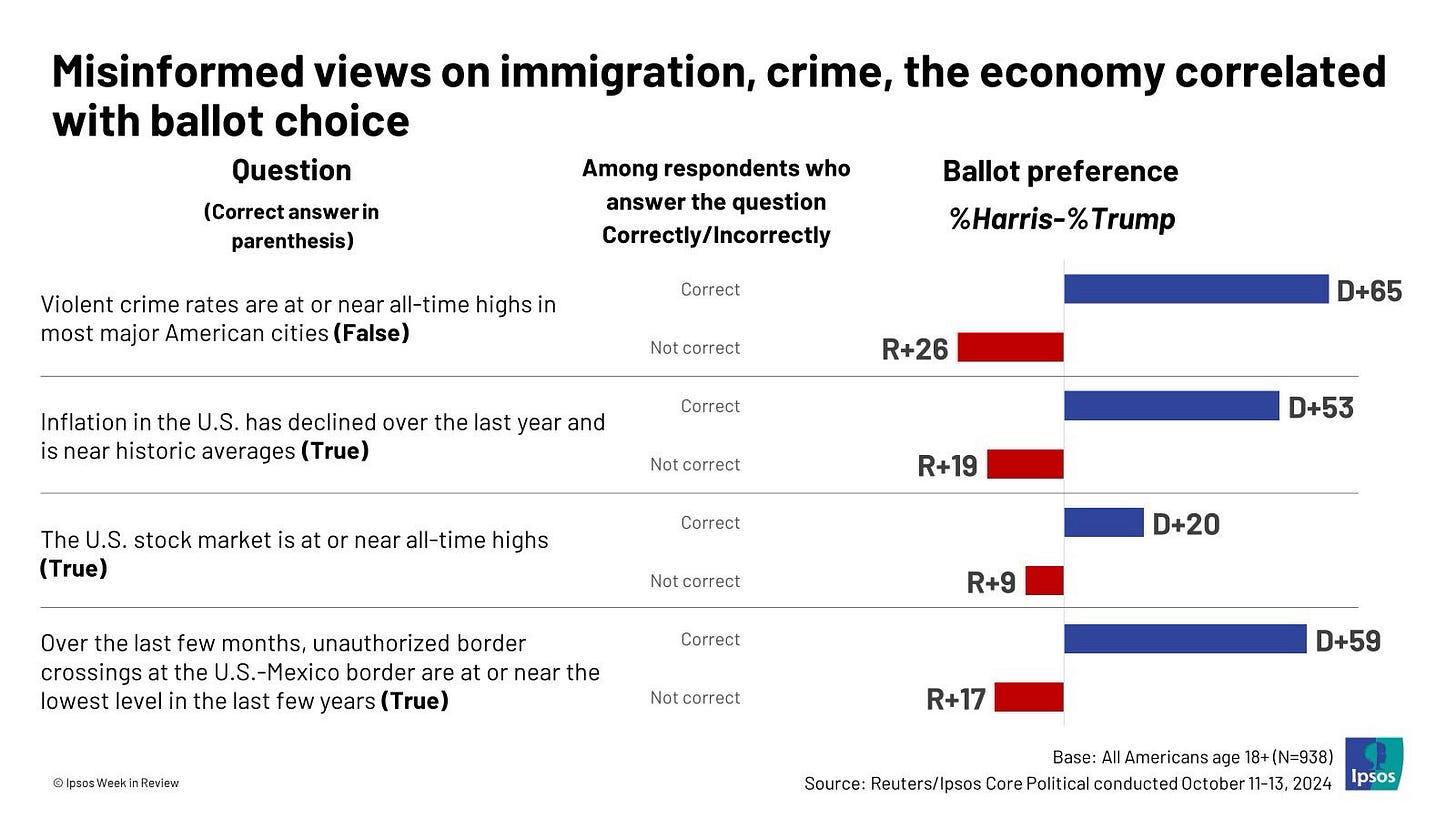

It’s also pretty clear that if misinformation didn’t tilt this election, at the very least Trump’s voters were badly misinformed, including about crime.

But as with the Texas judicial races, Trump’s comparatively narrow victory will have consequences wholly disproportional to his level of support. If justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito retire as some have speculated, Trump will have personally appointed a five-vote Supreme Court majority that will remain in place for decades. If any of the three liberals leave the bench, he’ll have influenced the court more than any president since FDR. And given this court’s disregard for precedent, Gideon, Miranda, the Exclusionary Rule, and federal habeas review, who knows how many other constitutional protections for criminal defendants could be at risk. We could see the court overturn its own precedent when it comes to non-unanimous death sentences, capital punishment for non-homicide crimes, executing the mentally ill, or executing people who were minors at the time of their crimes.

Trump has also vowed to execute every prisoner on federal death row, and to expand the federal death penalty to include drug traffickers and migrants who kill U.S. citizens. He has vowed to “unleash” police officers by granting them immunity from criminal prosecution. It isn’t clear what he means by that — or if he even knows what he means — but at the very least, we’re likely to see an end to federal oversight and federal prosecutions of local police for civil rights violations.

Trump has threatened to launch investigations of progressive prosecutors or to withhold federal funding from their districts, imposing his will on blue jurisdictions whose voters want reform. And he has of course promised to weaponize federal law enforcement to settle grudges, exact retribution, and protect his interests.

All of these promises came in a campaign in which Trump and his surrogates repeatedly and brazenly lied about national crime, migrant crime, and crime in blue cities, and in which those lies were then amplified by the right wing ecosystem. That ecosystem is no longer just Fox News and conventional right-identifying outlets. It includes platforms funded by the new donor class that purport to be neutral or at least claim not to be left-right aligned, like Bari Weiss’s Free Press. It also includes Musk’s X, and the panoply of manosphere podcasts.

Meanwhile, Musk has said he plans to build on his success in Texas and start spending his fortune — which grew substantially after Trump’s win — on defeating progressive prosecutors around the country. As we saw last week, and as we saw with the recall of Chesa Boudin, those prosecutors’ actual impact on public safety — and whether they’re supported by the communities who elected them — is largely irrelevant. Musk and his fellow broligarchs have shown their determination to impose their preferences on communities all over the country. They’ve also demonstrated that the facts on the ground don’t matter — they have the resources and information outlets to create their own reality.

As with just about everything else right now, the future of criminal justice reform seems grim.

Rich dudes in Dallas got three propositions on the Nov. general election ballot, and two won. The most dangerous one was not aimed at police reform, but rather an attempt to get the City to hire more police officers. Nine hundred more, to be exact, and the city is required to devote 50% of new city revenue to police and fire pensions. That's about a 25% increase in the number of officers Dallas already has.

Just about every credible person in city government, and even the Dallas Police Association (union) says that's impossible. As former mayor, Mike Rawlings says; “Because you want to do it right, you want to make sure that the right ones [get] hired, you want to make sure they’re trained appropriately. The way that proposition is written, it’s going to be very, very dangerous to hire all those officers at once.”

Here's what the DPA spokesperson said: “Dallas Police Association, which represents thousands of Dallas police officers, is strongly opposed to all three of these amendments — which were contrived by a small group of people who do not live in Dallas, with no open dialogue, no experience on the subject matter and no communications with police association leaders that would be impacted by these amendments." That's pretty strong stuff from a police union!

If our broligarch overlords take over, it's possible we'll look back on Trump as not that bad.

Edited to add a cite for the source: https://www.texastribune.org/2024/10/28/texas-dallas-police-propositions-amendments/

Radley, I became a paid subscriber just to comment on this column.

My background: I've lived in Oakland since 1981, so I've seen some significant crime waves. The '80s and '90s were particularly bloody years, many of which featured triple-digit homicide totals. Since then, things have improved considerably, but this remains a poor city with extreme income inequality.

A quick correction: you should correct the spelling throughout the column of Mayor Sheng Thao's name!

Now on to the substance: it's important to note that the vote counts you cite throughout are not final. Alameda County still has a substantial (100,000 plus) number of ballots to count. Yes, we're slow, but this is in part because California counts all ballots received through the Tuesday following Election Day, as long as they were mailed on or before November 5. In addition, it is not clear to me yet by what margin Oakland voters will have rejected Price. Her 2022 victory was driven by Oakland voters (we're the largest city in the county), and I suspect her 2024 recall will be driven largely by non-Oakland votes. That doesn't mean that she will WIN in Oakland...just that this city was her base, and that I suspect she will lose here by a much smaller margin than she loses in the rest of the county.

Both recalls were funded (as you note) by tech and real estate interests. There is NO WAY either recall would have got off the ground without that money. The recall process has been permanently tainted by Citizens United. Rich people have figured out a way to unseat politicians they don't like. This started with Boudin; we are already seeing hints that Contra Costa DA Diana Becton will be next on their hit list.

Pamela Price and Sheng Thao weren't perfect, of course, but anti-democratic forces wouldn't even allow them to complete their terms. It's a dangerous time.