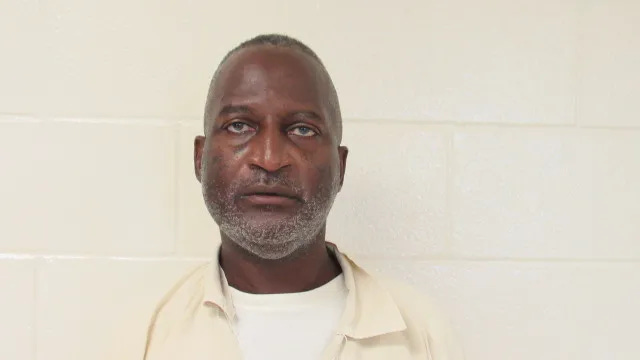

Sarah Huckabee Sanders denies clemency to Charlie Vaughn

The governor offered no explanation for refusing Vaughn, a mentally disabled man who has been in prison for 30 years for a crime he did not commit

I have an unfortunate update on Charlie Vaughn, the Arkansas man who has spent the last 30 years in prison for a crime he almost certainly did not commit. I published a long investigation into Vaughn’s case just over a year ago to kick off this newsletter.

A couple weeks ago, I reached out to Stuart Chanen, Vaughn’s attorney, to catch up on the case. Chanen and I finally connected yesterday. He told me that over the summer, he had sent Vaughn’s clemency petition to Arkansas Governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders.

It did not go well. But before I get to that, here are some of the key points from Vaughn’s case:

Vaughn and three other people were convicted for the 1988 murder of Myrtle Holmes, an 81-year-old woman in Fordyce, Arkansas.

Despite suffering from mental illness and a severe developmental disability, Vaughn was held in jail for nearly a year, during which he repeatedly denied any involvement in the crime. There’s no record he was ever evaluated by a mental health professional to assess his competency.

A judge did finally order an evaluation, but instead, the local sheriff sent an informant into the jail to extract a confession from Vaughn. This would not be disclosed to defense counsel for more than 20 years.

The sheriff then publicly announced that Vaughn had confessed. To that point, there was no record of such a confession. But Vaughn was then assigned an attorney, who Vaughn says told him his only hope to avoid the death penalty was to confess and implicate the other people suspected by local officials.

Despite representing a man who faced a life sentence or possible death penalty, Vaughn’s attorney was paid just $200.

Vaughn then confessed and implicated the others. His confession contradicted several known facts about the crime. Most notably, Vaughn claimed that he and another man raped Holmes. Even back then, DNA testing on semen found in the victim excluded both Vaughn and the man he implicated.

The judge sentenced Vaughn to life in prison, but seemed suspicious of Vaughn’s confession, saying, on the record, “I’m sure that some governor somewhere down the road will reduce the sentence or commute it to a term of years.”

The three other people Vaughn implicated were tried the following year. Vaughn testified against them. The jury deadlocked, causing a mistrial. By the time they were tried again, Vaughn had recanted his confession and implication of the other three. Despite this, all three were convicted in the second trial.

In 2015, the Innocence Project began representing one of the other people convicted in the murder. As they were about to conduct DNA testing, a man named Reginald Early confessed to the crime. Early was a suspect early on, and was one of the three people Vaughn implicated. But early insisted that he acted alone, and barely knew Vaughn and the other two. In fact, he said he had considered confessing shortly his arrest, but when he saw that three other people had been arrested — all of whom he knew had nothing to do with the crime — he concluded that the state didn’t know what it was doing, and decided to take his chances with a jury trial.

Unlike Vaughn’s, Early’s confession was consistent with the evidence and what police know about the crime scene.

The only other evidence against Vaughn and the others were statements from various witnesses who claimed to have seen some combination of the four suspects together, or to have overheard them making inculpatory statements.

Nearly all of these witnesses were police informants. At the time, several were addicted to drugs, suffered from mental illness, or both. All but one of these witnesses has since recanted.

Based on all of this, the two other people convicted based on Vaughn’s confession have since had their convictions overturned and have been released. One has since passed away. Both were represented by seasoned attorneys with ample experience litigating innocence cases.

The state of Arkansas would later argue that Vaughn should have been aware of the developments in the other two cases, and because he didn’t file a claim within a year of when the attorneys in those cases uncovered new evidence, he had failed to show due diligence, and therefore is barred from benefiting from that new evidence.

When that evidence was revealed, Vaughn was sitting in an Arkansas prison cell. He had no attorney at the time. Vaughn is also illiterate. During questioning for an evidentiary hearing in one of the other two cases, Vaughn appeared to think the hearing was for him.

The two people were released were given relief by the federal courts. They had had no recourse in Arkansas state courts. Even so, they barely won their cases. Two federal magistrates actually recommended they be denied, not because the evidence against them was strong, but because they had missed various deadlines and thus were blocked from having their claims considered on their merits.

Charlie Vaughn had tried to get federal relief in the 1990s, with a crushing, hand-written plea for his freedom. That note meant he had already been denied in federal court, so he faced a higher burden to have his claims heard again. A panel from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit denied Vaughn without explanation.

Vaughn’s mental illness has gone untreated in the 30 years he has been in prison.

Should he ever be freed, a childhood friend who owns a local farm and business has said Vaughn would have a bed, a job, and a home for as long as he needs one. He’ll have a stable, nurturing environment around him.

Myrtle Holmes’ niece, who now represents Holmes’ family, told me she has gave doubt about Vaughn’s guilt, and has advocated for his release.

I can’t recall covering a case as sad and affecting as this one. One common refrain among people who have advocated for Vaughn — his first court-appointed attorney, the Midwest Innocence Project attorney who represented one of his co-defendants, Stuart Chanen — is that they think about him nearly every day. I do as well.

Chanen began putting together Vaughn’s clemency petition shortly after Vaughn lost in federal court. He first submitted the petition to the Arkansas Parole Board last year. The board found his petition “without merit.” But in Arkansas, the governor isn’t obligated to follow the board’s recommendations, so Chanen had hoped to get the petition in front of then-governor Asa Hutchison before he left office. But when the Arkansas Times asked the governor’s office to comment on the status of Vaughn’s request, the office replied that in Arkansas the governor is required to provide 30 days notice of an intent to grant clemency. By the time the office received the petition, Hutchison had less than 30 days remaining in office.

Chanen would have to persuade governor-elect Sarah Huckabee Sanders instead. She would not appear to be a receptive audience. Since taking office at the start of the year, Sanders has staked out a Trumpian line on criminal justice. In April she signed a bill that revoked parole for some crimes, made it more difficult for others, and reduced the amount of time prisoners can have taken off their sentences for good behavior. The bill also green-lights construction of a new 3,000-bed prison.

Still, one can take a hard, law-and-order line on sentencing and still be opposed to locking up innocent people. Indeed, you could make a strong argument that you can’t be authentically “law-and-order” without vigorously opposing the incarceration of innocent people. And yet many self-described law-and-order politicians seem to be okay with it — or at least have little interest in knowing when it has happened.

But there’s another reason why Sanders may have been reluctant to act. She is of course the daughter of former Arkansas governor Mike Huckabee, and her father came under intense scrutiny for granting clemency and freeing prisoners who then went on to commit other crimes, including one man who later killed four police officers in Washington state.

But Huckabee’s clemencies and commutations were quite a bit different than what Sanders is being asked to do in Vaughn’s case.

There are two ways to use the pardon and clemency power. Well, two legitimate ways. There’s a third way, which is to reward cronies, campaign contributors, and political allies. Alas, this use also appears to be the most common.

The first legitimate way to wield the power is the way Mike Huckabee used it — as a way of conferring redemption and forgiveness.

I happen to think pardons and clemency should be granted far more often, including for these reasons. But it’s interesting that this is the most common legitimate use of the power. There’s a certain arrogance about to it.

These pardons go to guilty people whom a governor has deemed sufficiently redeemed. Redemption is of course subjective, and granting pardons or clemency for this reason allows a governor to showcase his or her values. For example, such pardons often go to people who have found religion (there’s a reason why so many pardons are handed down around Christmas). Former Mississippi Governor Haley Barbour had a habit of pardoning men who had killed their wives or girlfriends, but whom he then got to know when they worked as trustees in the governor’s mansion.

The second legitimate reason for granting a pardon or clemency is really the reason the U.S. Constitution vests the power in the president. It’s the way it was intended to be used, and it’s the way it would be used in Vaughn’s case: as last check and balance to prevent injustice.

Here’s Alexander Hamilton, in Federalist 74:

The criminal code of every country partakes so much of necessary severity, that without an easy access to exceptions in favor of unfortunate guilt, justice would wear a countenance too sanguinary and cruel. As the sense of responsibility is always strongest, in proportion as it is undivided, it may be inferred that a single man would be most ready to attend to the force of those motives which might plead for a mitigation of the rigor of the law, and least apt to yield to considerations which were calculated to shelter a fit object of its vengeance.

This is the most righteous use of the power. It’s also the least frequent justification for using it. Governors don’t like to second guess the justice system, even when there are plenty of reasons for them to do so. It’s seen a slap in the face to the police and prosecutors who worked on the case.

This brings us back to Sanders and Charlie Vaughn.

After filing Vaughn’s petition last June, Stuart Chanen met with Cortney Kennedy, the chief counsel for Gov. Sanders. Chanen says they talked for about an hour and that afterward, he left the meeting feeling encouraged. He thought Kennedy had been genuinely moved by Vaughn’s story.

A month later, Chanen sent an email to inquire about the status of Vaughn’s petition.

He received this reply from Kennedy:

Good afternoon, Mr. Chanen,

The Governor completed her review of Mr. Vaughn’s file last week. Unfortunately, she has chosen not to grant clemency at this time. He will be able to reapply in 6 years, pursuant to statute.

Sanders’ office has given no explanation for her denial of clemency. “I’m just grief-stricken,” Chanen says. “If ever anyone were deserving of this, it’s Charlie Vaughn.”

Chanen is now preparing a habeas petition for the Arkansas Supreme Court. But the odds of getting any relief are daunting. Arkansas law provides no way back into court for prisoners who have exhausted their appeals, even with factual innocence claims.

It seems likely that, at minimum, Charlie Vaughn will spend another six years in prison.

Great job illustrating the failures in the justice system. It’s really sad and frustrating that this has happened, especially with all the doubt you clearly presented. The politics of punishment strikes again.

When he was governor of Texas, GWB approached his use of the pardon power by saying that his role was to review the case and make sure that all proper procedure etc were followed. But that's literally the job of the courts. His job as governor was to dispense grace, not due process!

We need better politicians who understand the theory of government.