Last July, I published an op-ed in the New York Times about the town of Golden Valley, Minnesota. Here’s the gist: After the George Floyd protests, officials in the wealthy, liberal, mostly white Minneapolis suburb began to reckon with the town’s long and ugly racial history. As part of that reckoning, the town implemented some diversity, inclusion, and equity initiatives, including at its police department. The town also hired its first black woman executive as an assistant chief, and shortly after, first black police chief. The town also fired a white officer who made racist comments during a Zoom meeting.

In response to one or some or all of these developments, nearly half the town’s department quit — all white officers. Despite this, I pointed out, crime actually went down in Golden Valley over this period.

Last week, an analyst named David Zimmer at the American Experiment, a conservative think tank, wrote a response to my op-ed under the headline, “Less cops, less crime: Claims that police quit and crime dropped in Golden Valley don’t hold up.” Zimmer’s post also prompted a writer at the right-wing blog Hot Air named David Strom to come out swinging at my op-ed.

Most of their criticisms are misguided. But they do make one critique that I think is fair. So let me start there.

Zimmer, a retried longtime Hennepin County sheriff’s deputy, points out that once Golden Valley PD was down to just four patrol officers, the town contracted with the Hennepin County Sheriff’s Department to have deputies from that agency handle day shifts — or about 50 percent of patrol duties. Zimmer thinks I should have pointed this out. He has a point.

First, some clarification. The point of my op-ed was not to argue that “less cops means less crime.” I was making a more nuanced point. The message implicit in the “Ferguson Effect” — at least as it’s promoted by law enforcement groups and their advocates — is that reforms intended to hold abusive, corrupt, and racist police officers more accountable results in more cops quitting en masse, cops who stop doing their jobs, or who just do their jobs less effectively. This then results in more crime. We’ve seen this argument over and over, going back to the protests in Ferguson themselves.

I’ve always found this to be a puzzling defense of police. It’s essentially arguing that police should get veto power over the policies that govern their performance and behavior, and that if cops don’t like those policies, they’ll hold the communities they serve hostage to the threat of crime until they get their way. As I wrote in the op-ed, the message to marginalized communities here is dangerous and unacceptable: You can have constitutional, accountable policing, or you can have a safe community. But you can’t have both.

In Golden Valley, officials implemented some policies to address these concerns of marginalized communities. These policies appear to be widely popular in the town — this year residents elected the town’s first black woman mayor, a candidate who pledged to continue the reform policies of the previous administration.

Yet despite the wishes of the people they serve, half the police department quit. You may disagree with some or all of these particular policies — I’ve certainly seen language in some DEI materials that seems excessive — but it’s worth noting that police officers in Golden Valley are paid exceptionally well to police a town with very little crime. It’s a cushy gig. These cops gave all of that up because they had to sit through some diversity training, or because the town hired a couple (Black) executives from outside the department, or because a colleague was fired for saying racist stuff. It seems perfectly reasonable for a town to conclude that those aren’t the sort of officers it wants on its police force.

And that’s the approach Golden Valley took. The town didn’t try to to lure the quitting officers back. It didn’t fire or force out the Black executives it had hired. It didn’t halt the DEI training, or rehire the fired cop. Instead, the town adapted. They took measures to fill in the gaps while they looked to hire officers more in line with the town’s values. As Zimmer himself points out, the town also also replaced some patrols with “community service” officers who don’t have enforcement power. I think this is a great idea, too. There’s evidence that simply having “watchers” in the community can prevent crime without coercion — it’s what John Pfaff has called the sentinel effect.

These policies seem to have worked. Contrary to what we’re regularly told would happen, the town did not descend into anarchy.

Here’s my concluding paragraph, which I think captures the thesis of the piece:

When people don’t trust law enforcement, they stop cooperating and resolve disputes in other ways. Instead of fighting to retain police officers who feel threatened by accountability and perpetuate that distrust, cities might consider just letting them leave.

So let’s get back to where I think Zimmer has a fair criticism: I did not point out in my piece that after half its police force quit, Golden Valley contracted some of its patrol shifts to the sheriff’s department.

Again, I didn’t include this because my argument was not that more cops means less crime. Unfortunately, the headline for the op-ed (which I didn’t write, and which I don’t think adequately summarizes the piece) was this: “Half the Police Force Quit. Crime Dropped.” Consequently, the piece was touted on social media — by people who both agreed and disagreed with it — with language like, “NY Times says less cops means less crime!”

I should have anticipated that the piece could be characterized that way. And because that is how it was characterized, I certainly understand why some might think it was misleading to leave out the contract with the sheriff’s department. I don’t think it was misleading if you read the entire piece, particularly without the headline. But headlines set the tone for how we take in the rest of an article. So it would have been prudent to include it.

That said, the other criticisms Zimmer and Strom make of my piece just aren’t valid. Zimmer’s main beef is with my claim that crime in Golden Valley has gone down. He points out that the crime statistics on the town’s website only include crimes reported by Golden Valley cops. So they don’t reflect the crimes that Hennepin County sheriff’s deputies reported while patrolling the town under the contract.

I checked with Chief Green about this, and Zimmer is correct — or at least he was correct that this was the case at the time my op-ed was published. Golden Valley did begin integrating the statistics in August.

Zimmer then exlpains that to double check my work, he submitted a data request with the Hennepin County Sheriff’s Department for the crime statistics its deputies generated while patrolling in Golden Valley. And sure enough, these statistics appear to show that crime actually increased in the town.

Zimmer writes:

The combined data comparison from January through June 2022 and 2023 indicates.

— Calls for Service are up 16 percent.

— Arrests are up 21 percent.

— Citations (misdemeanor offenses) are up 40 percent.

— Crimes Against Persons are up 49 percent.

— Crimes Against Property are down slightly at 4.8 percent.

— Crimes Against Society (drug offenses, liquor law violations, weapon offenses) are statistically down approximately 48 percent, but these crimes are most often detected and responded to through proactive law enforcement, which has been dramatically and negatively impacted by the staffing situation. This “reduction” should not be viewed as a drop in this criminal activity, but rather as a lack of proactive law enforcement efforts.

No matter how the data is analyzed, the claim that Golden Valley lost half its police force and saw a reduction in crime is misleading. When reform advocates manipulate crime data to suggest fewer officers result in less crime, their hidden agendas become exposed.

Golden Valley is facing a prolonged public safety crisis of its own making, and citizens should look no further than the elected officials who created it.

“Crisis” feels a bit hyperbolic, here. Even accepting Zimmer’s statistics at face value, Golden Valley is still an exceptionally safe community. When you start breaking an already small number of crimes into even smaller categories, you end up with some really tiny numbers. For example, the number of kidnappings in Golden Valley went from zero in 2022 to three in 2023. So you could accurately say that kidnappings in Golden Valley are up infinitesimally!

Over at Hot Air, Strom riffed on Zimmer’s data to post a much nastier response.

It is quite the tale of woe and intrigue, that ends happily with crime dropping due to the reduction in the police force and the triumph of a good Black man over mean racists.

Only it is all crap, as the Minnesota think tank Center of the American Experiment shows with just a few phone calls that Balko apparently didn’t bother to make . . .

This is what we call pushing The Narrative™. Balko has been a reporter for years, has written two books, and knows how to do research. Either he is a drooling idiot–and he had to go through the New York Times’ fact-checkers so they had to be idiots too–or they did a sleight of hand, knowing they were not telling the truth . . .

Radley Balko? He is a criminal justice reform advocate, doing his best to push the defund the police narrative. I can’t say if he is sharp as they come, but I doubt he was so stupid that he didn’t know he was playing fast and loose with the facts.

This, my friends, is how it is done. Narrative building in action.

Just to be clear, I’ve never argued that we should defund or abolish the police. I do think we could — and should — significantly reduce the police footprint by delegating many of the things we ask them to do (traffic enforcement, school safety, mental health crises, drug enforcement, etc.) to non-profits, community groups, or other government agencies more suited to handle them.

But let’s get to the crime stats driving both of these responses. Zimmer doesn’t provide a link to the raw data he relies upon for his piece. He just claims to have made a data request from the sheriff’s department, and then summarizes what they gave him. And yes, his figures certainly do seem to contradict my contention that crime in the town went down.

But there’s an explanation for that. It turns out that the Hennepin County Sheriff’s Department and the Golden Valley Police Departments have very different policies when it comes to writing police reports and collecting crime data. I spoke with Golden Valley police chief Virgil Green about all of this on Friday. Green told me that under Hennepin County Sheriff’s Department policy, every police call or police response results in a report, which is then included in the crime statistics. Golden Valley officers only write reports for calls or responses when there’s evidence of a crime.

Here are a few examples of how these different approaches can play out:

— The police are called to a bar or a party because someone is drunk and refuses to leave. But by the time the officers arrive, the drunk guy has left. Under sheriff’s department policy, this would result in a police report and documentation of some sort of crime — public intoxication, disorderly conduct, trespassing, etc. If a Golden Valley officer responded, it would not.

— You return home to find that your front is door open. You call the police. But there’s no evidence of a break-in and nothing was stolen, Golden Valley wouldn’t issue a report. The sheriff’s department would, which would result in an additional reported crime.

— A neighbor calls the police after hearing a couple next door having a heated argument. When the police arrive, neither party alleges any abuse, and there are no signs of assault or battery. Again, the sheriff’s department would write a report and document a crime here, while Golden Valley officers would not.

You can see how these different approaches would result in very different crime statistics.

At Hot Air, Strom accuses me of deliberately failing to inform readers about the sheriff’s department statistics. And he’s right! In fact, I didn’t even bother to look for those figures.

But I didn’t rely on Golden Valley PD statistics, either. When I first interviewed Chief Green several months ago for the op-ed, he told me his crime analyst assured him that crime in the town had dropped. But Green also told me about the town’s contract with the sheriff’s department, and that they’d been having some difficulties synchronizing the two departments’ different approaches to data and police reports.

Green didn’t go into quite as much detail about the differences between the two departments in our first interview than in our conversation last week, but it was clear from what he did tell me that comparing police-collected data from before and after the town’s contract with the sheriff’s department would be a big mess, and not at all informative.

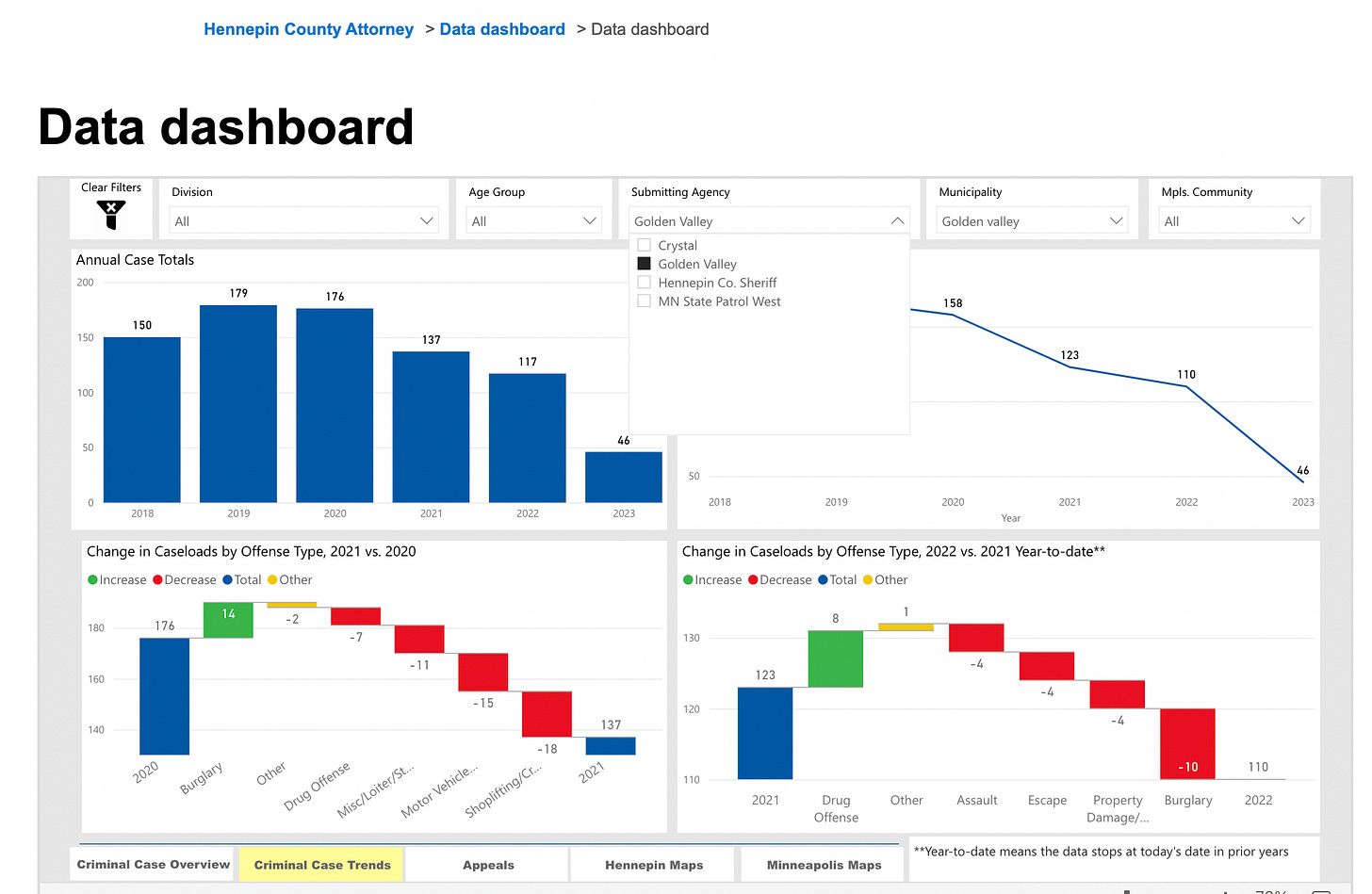

But as a journalist I also couldn’t rely solely on what Green told me. He of course has an interest in showing me statistics that reflect well on him. So I looked for other sources of data to check his claim. Fortunately, I found such a source with the Hennepin County Attorney’s Office, which runs a really useful data dashboard.

The dashboard is continually updated, and the graphs comparing the current year to previous years are “year to date.” Because of that, I can’t reproduce the exact results I got back when I was reporting the NY Times piece.

But I can show you what it says now, which is similar. And what it shows (a) persuasively demonstrates that crime is down in Golden Valley, and (b) backs up Chief Green’s explanation for why the data Zimmer got from the sheriff’s department might suggest otherwise.

Here’s what the dashboard shows for charged crimes in Golden Valley over the last six years. Keep in mind that Golden Valley started the racial justice initiatives in 2020, started losing police officers in 2022, and then contracted with the sheriff’s department in early 2023.

The relevant graph here is the line graph on the upper right.

The graph shows a 23 percent drop in charged cases year to date this year from last year, and a 25 percent drop since 2021.

You can also tweak the dashboard to show how many charged cases in a particular municipality originated from officers who work for a specific police department with jurisdiction in that county. This is even more helpful. If Chief Green is correct about the differences between his department and the sheriff’s department in how they write police reports, we should see a big increase in the number of charged crimes in Golden Valley referred by sheriff’s deputies so far in 2023, and a big decrease in crimes referred by the Golden Valley Police Department for both 2022 and 2023.

That’s exactly what it shows. Here are the charged crimes in Golden Valley reported by sheriff’s deputies:

And here are the crimes that reported by Golden Valley PD officers:

Pretty persuasive!

But wait, law-and-order types may say. Didn’t Hennepin County recently elect a progressive prosecutor, who took office at the start of 2023? Maybe the drop in charged crimes in Golden Valley is merely the result of a leftist prosecutor refusing to bring charges.

We can test this theory, too. If this were true, we would expect to see a drop in charged cases in Hennepin County more broadly. But we don’t.

Here’s what that graph looks like:

Moreover, this increase in charged crimes across the entire county came even as overall crime in the county dropped, and violent crime dropped in both 2022 and so far in 2023. (Property crime went up slightly, driven largely by a huge increase in auto thefts that’s been mirrored in cities across the country.)

I’ll point out here that using charging data from a prosecutor’s office isn’t foolproof, and it isn’t the best way to figure out how many crimes were committed overall. It’s only going to include crimes that were serious enough to merit charges and for which police have arrested a suspect.

But it’s a pretty good way to assess which way things are trending. Year to year, the ratio of charged crimes to uncharged crimes will be pretty consistent. And it’s certainly a better way of gauging whether crime in Golden Valley has gone up or down than trying to compare stats from a year in which the town did all of its own policing against a year in which it contracted about half its patrol shifts to an agency that uses a substantially different method of collecting data.

So why didn’t I explain all of this in the op-ed? Mostly because it was a 1,000-word piece. This post itself is 3,000 words. As a journalist, you have to make choices about what you lay out in detail and what you summarize. I was comfortable quoting Green’s assertion that crime was down in his town because the most reliable, independent, and consistent year-to-year data I could find — the data from the prosecutor’s office — confirmed what he told me.

Could the lesson from Golden Valley be applied elsewhere? I don’t know. It’s by no means a representative community, which I acknowledged in the op-ed. But there have been other examples in which “de-policing” was followed by a drop or no change in crime. There are also examples where it was followed by an increase. There are also countless variables in all of these places that have little to do with de-policing, but probably also affected the crime rate. It’s a contentious and ongoing debate in criminology.

I thought Golden Valley was an interesting case study, and that it was worth writing about.

Finally, I want to address this point from Zimmer:

Crimes Against Society (drug offenses, liquor law violations, weapon offenses) are statistically down approximately 48 percent, but these crimes are most often detected and responded to through proactive law enforcement, which has been dramatically and negatively impacted by the staffing situation. This “reduction” should not be viewed as a drop in this criminal activity, but rather as a lack of proactive law enforcement efforts.

This is really cuts to the heart of this discussion. It’s the “broken windows” debate all over again. People like Zimmer and Strom believe that aggressively policing low level drug offenses, liquor laws, gun possession (i.e. stop and frisk), vagrancy, trespassing, and other “quality of life” crimes leads to a reduction in more serious crimes. There’s little evidence for this. (It’s also a misappropriation of the work that gave us the term “broken windows,” which was about fixing blight, not aggressive policing — but that’s another topic.) Golden Valley moved away from this sort of policing, and the number of crimes serious enough to merit charges from the county attorney went down.

Some of us believe that targeting poor and marginalized people for petty offenses and crimes born of poverty would be objectionable even if it did lead to a decrease in more serious crimes. But it isn’t at all clear that it does. And the Golden Valley story is a data point on my side of the debate, not theirs.

It's difficult to find clarity in a discussion of law enforcement, especially when the subtext is always, How do we "police" and protect the US while upholding its constitutional and democratic norms?

Mr. Balko's right wing critics, even when they are making reasonably good points, are nevertheless part of the right's outrage machine: their job, therefore, is to generate outrage, to darken the picture, to be ominous, to create a panicky sense that chaos and violence are as near as the next attempt at police reform.

Mr. Balko's job is to present the facts with as much clarity and respect (and as little outrage) as he can muster. He does it well.

“It seems perfectly reasonable for a town to conclude that those aren’t the sort of officers it wants on its police force.”

100%.