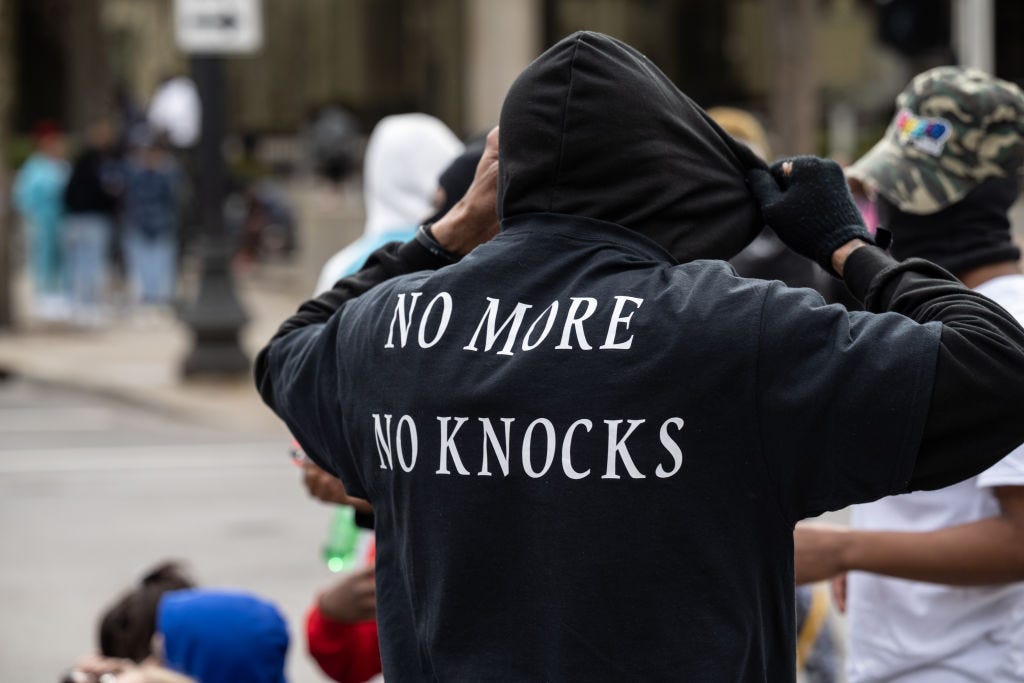

No-knocking in North Carolina

More evidence that the courts have failed to protect the Fourth Amendment

In 2006, the U.S. Supreme Court court ruled in Hudson v. Michigan that the Exclusionary Rule no longer applies when police serve a search or arrest warrant with an illegal no-knock raid. The court did not overturn the requirement that police knock and announce themselves before entering a private residence; it just removed the only real incentive for them to continue following it.

As I’ve written at length over the last several years, we now have documentation that after Hudson, many police agencies just flagrantly dispensed with the knock-and-announce rule entirely. We know, for example, that police agencies in Little Rock; Myrtle Beach, South Carolina; and Louisville have routinely violated the rule for years, often with the acquiescence of the judges who sign off on warrants, and probably without even knowing that they’re doing so.

These were all routine, systematic violations of the Fourth Amendment. But because there is no longer any real way to enforce the knock-and-announce rule, no one with any authority in those places seemed to care. In South Carolina and Louisville, these raids ultimately led to tragic outcomes — in Louisville, it was the killing of Breonna Taylor, and in Myrtle Beach, it was the maiming and near-killing of Julian Betton. Both resulted in successful lawsuits against the police agencies involved and subsequent reforms. But it took a tragedy for anyone in power to care.

Earlier this month, Jeffrey Welty of the University of North Carolina published a study of the use of no-knock tactics in that state and the legal landscape that governs them.

You won’t be surprised by what he found:

Among the conclusions are: (1) there is no explicit authority for North Carolina judicial officials to issue no-knock warrants; (2) judicial officials sometimes issue such warrants anyway; (3) no-knock warrants seem to be very rare; (4) when an application for a no-knock warrant is granted, the resulting warrant does not always include an express judicial determination regarding the need for a no-knock entry or an express judicial authorization of such an entry; and (5) quick-knock entries, where officers knock and announce their presence and then immediately force entry, may be widespread.

Note that finding number five basically invalidates finding number three. As I’ve pointed out many times before, and as Welty points out in his study, there is no practical or legal difference between a no-knock and a “quick-knock” raid. The entire point of the knock-and-announce requirement is to give the occupants of a home time to answer the door peacefully, and to avoid unnecessary violence and destruction of property. If police announce themselves just as, or just a few seconds before they batter down the door, the occupants aren’t given that opportunity. At that point, the announcement is just a perfunctory ritual to an anachronistic Fourth Amendment protection that no longer exists.

Welty acknowledges that there is no hard data on "quick-knock” raids in North Carolina. That isn’t surprising. We rarely even get data on the use of no-knocks. His conclusion that the tactic is widespread in North Carolina is based on his interviews with law enforcement officials. But if he’s right, and there’s really no reason to think he isn’t, we can add the state to the list of places where police have been routinely conducting illegal raids for years.

Welty’s conclusion that these raids appear to be ongoing despite no explicit authorization for them from the state legislature or the state’s courts is also interesting. The knock-and-announce requirement dates back several centuries to English common law. Though the U.S. Supreme Court only formally recognized the rule as part of the Fourth Amendment in 1996, the court acknowledged in that decision that the protection is ingrained in the Castle Doctrine, or the idea that the home should be a place of peace and sanctuary. As we’ve seen in other states, the courts in North Carolina have simply let the rule atrophy over time by refusing to sanction the police who violate it.

This all particularly interesting to be coming from North Carolina. As I wrote in my first book, North Carolina was home to Sen. Sam Ervin, one of the few politicians who took this issue seriously.

Ervin was a fascinating character. He began his career as a segregationist and opponent of teaching evolution in public schools, and ended it as an ardent civil libertarian and the chair of the Watergate hearings that helped bring down the Nixon administration. He deployed an “I’m just a country lawyer” shtick to disarm his opponents, but could quickly devastate their position with his wit and intellect.

Nixon famously swept into office in 1968 with a pretty radical (for the time) anti-crime platform. Because the federal government had little power to impose crime policy on the states (again, at least at the time), Nixon wanted to make Washington, D.C. a test city for his agenda. And the no-knock raid was a big part of that agenda.

The idea of giving the police advance authorization to break down the doors of suspected drug dealers wasn’t a policy police leaders really even wanted. New York state had passed the first no-knock law in the 1960s, and police there barely used it. Instead, the no-knock raid was a wedge issue Nixon campaign operatives pushed to signal they were tough on crime to win over Nixon’s “silent majority.”

Nixon’s allies in Congress introduced his crime bill in 1970, a bill that among other things would authorize no-knock raids both D.C. police and for federal narcotics cops.

He’d encounter unexpected opposition from Ervin, who objected to both the no-knock provisions and a provision to end cash bail in D.C. The former segregationist would, ironically, become passionate advocate for the rights of the residents of a city that at the time was 70 percent black.

Here’s Ervin biographer Paul Clancy on Ervin’s fight against the bills:

On July 17, 1970, Ervin treated the few senators in the chamber and the visitors in the galleries to a tour de force. Using small Senate envelopes on which he had scribbled page numbers of the Bible, the Constitution, and his favorite history books, he spoke extemporaneously for four and a half hours. He contemptuously took the legislation apart sentence by sentence, showing at each point where it did violence to the Constitution, hoping to draw attention to what the Senate was doing. Word got around that the old constitutionalist was on his feet, fighting the Administration’s crime bill.

He said the no-knock statute would give policemen “the right to enter the dwelling houses of citizens of the District of Columbia in the same way that burglars now enter those dwelling houses,” and that preventive detention was “absolutely inconsistent with the policies that have prevailed in this nation since it became a Republic.”

He scoffed at the term “necessity,” which many of his fellow senators were using to justify the bill . . . And he gave the Senate his simple prescription for living: “Mr. President, the supreme value of civilization is the freedom of the individual, which is simply the right of the individual to be free from government tyranny.”

The District of Columbia provisions, he shouted, arms waving and voice trembling, “ought to be removed from this bill and transferred to the Smithsonian Institution, to manifest some of the greatest legal curiosities that ever have been evolved by the mind of man on the North American Continent.”

Hours later, still in a rage, Ervin implored the Senate “not to enact a bill which contains provisions that are absolutely hostile to the traditions which have prevailed in our country ever since it became a Republic. Once gone, the liberties which the bill threatened would be gone forever.”

He wasn’t wrong. The federal no-knock bills would ultimately pass, but were then repealed in 1975 after a series of botched raids, injuries, and deaths.

All of that would be forgotten when the drug war ramped back up in the 1980s. No-knocks have been a staple of the drug war ever since.

And we’ve been living with the consequences of this dangerous policy ever since.

Here’s just the most recent example of those consequences, from Ervin’s home state:

A Raleigh mother is still brought to tears remembering the day a team of Raleigh police officers raided the wrong house, terrifying her family.

The incident happened in 2020, but the family's attorney will be in court Wednesday to push for the release of the police bodycam video of the incident that ties back to a now-fired Raleigh police officer.

"I was in the house. I had just put my dinner on," said Yolanda Irving outside her old address on Burgundy Street in east Raleigh where the surprise encounter with RPD's Selective Enforcement Unit (SEU) happened. The SEU is the department's equivalent of a SWAT team, a tactical unit of highly trained and heavily armed officers.

In tears, Irving, returned to her old home for the first time in more than a year to recall that day in May 2020.

"I was right there, the second door," she said pointing to her side of the duplex. "SWAT came through my door. They pointed the weapons at me and chased my son up the stairs. They told us when they were bringing us downstairs to cup our hands over our heads."

Irving said that with guns drawn on her and her three children, officers ransacked the home. She said they were holding a search warrant; telling Irving they were looking for heroin and money . . .

The police officer in charge of the operation was Detective Omar Abdullah. He was fired from RPD late last year after a months-long investigation into dozens of bogus drug arrests based on bad information from a criminal informant that used fake heroin as evidence.

"They didn't find anything in my home. They didn't find no money. No drugs. No nothing. I never got an apology," Irving said.

The publicity from that raid resulted in this gobsmacking reaction from the Raleigh chief of police:

Amid growing criticism from local civil rights group over the Raleigh Police Department's use of no-knock and "quick-knock" warrants, Police Chief Stella Patterson said that the department does not use the warrants.

“As far as I am concerned and where I stand, that will be the position of this organization, that we do not seek or utilize no-knock warrants," she told WRAL News in an interview on Tuesday . . .

North Carolina law gives officers discretion in serving quick-knock warrants and says officers can force their way into someone's home if "they believe admittance is being denied or unreasonably delayed."

"[The law] just states you knock and announce your presence," Patterson said. "I have always been taught that you clearly knock on the door, and then you clearly announce, and then you enter at that time." . . .

“It is very clear that we won't serve no-knock warrants. Officers must knock and announce when executing a warrant," she added . . .

Patterson said that she believes it is reasonable for officers to knock, announce and make it clear they are at the door. But that doesn't mean officers are required to make sure that the person on the other side of the door has time to "get up, put their clothes on and come to the door."

I mean, that’s exactly what the knock-and-announce requirement is for. It’s why it has always existed. The problem is that the Supreme Court has since removed any incentive for public officials — from police chiefs to prosecutors to judges — to know it, to understand it, or to abide by it.

But it’s also at least a little understandable why Patterson would think that. As with the federal courts, North Carolina’s state courts have failed in their duty to uphold the Fourth Amendment. In 2002, the North Carolina Court of Appeals ruled that police officers who waited just six to eight seconds between announcing and breaking down the door had not violated the Fourth Amendment. That’s an absurdly short amount of time, particularly for a raid conducted early in the morning or late at night.

One of the truly maddening things about covering this issue for as long as I have is that you start to notice the same cycle of mistakes, excuses, promises for reform, and — inevitably — the same mistakes all over again.

That’s certainly true of North Carolina. Let’s start with the Raleigh area. In 1998, the Raleigh News & Observer published an investigation into drug raids in Wake County (via Lexis, so no link). The paper found that about one in four of the hundreds of raids conducted in recent years had turned up no incriminating evidence. That included these two cases:

Earl Richardson, 66, was on the wrong side of the odds. On June 1, police kicked in his door and forced him to the floor while they tore through his Worthdale neighborhood house for about half an hour until they realized they had the wrong half of a duplex.

The same thing happened about midnight one night in December, when a search warrant based solely on a confidential informant brought Raleigh's SWAT officers to the home of Priscilla Clark, who had often complained to police about drug dealers next door. Unfortunately, police came to her door instead.

"Oh my God, someone's coming in here to kill me," the 27-year-old rehabilitation technician recalls thinking. "I looked out my bedroom door and saw this big gun coming down the hall and a man dressed in black."

The officers herded her two children into her bedroom and kept them there for about an hour, while Clark, who was pregnant, tried to tell them they had the wrong house. Later, drug detectives apologized and admitted they made a mistake. They asked her to keep giving them tips, she said.

Compared to surveys from other jurisdictions over the years, a 75 percent success rate is comparatively pretty good. But is still is of course unacceptable. In this case, it meant that over 100 people innocent people were subjected to extraordinarily violent, volatile, and life-threatening tactics, along with hundreds more people suspected of low-level drug crimes (not to mention any innocent people who may have been in those homes at the time.

The News & Observer article — which was mostly deferential to the police agencies — also acknowledged that it was difficult to assess how often violent drug raids are conducted and how often they mistakenly hit innocent people, “because police throughout the region were lax about returning warrants to court, even though they are legally obligated to be prompt.”

Just a year after that article was published, this happened:

In May 1999, police stormed the Durham, North Carolina, home of 73-year-old Catherine Capps. Also in the house at the time was Capps’s friend, 71-year-old James Cates. Police say they obtained a warrant for the home after a confidential informant bought crack cocaine there. Capps had poor vision, was deaf, and according to her family, “could not even cook an egg without being extremely out of breath.” When police raided the home, they ordered Cates to stand. Hobbled by a war wound and frightened, Cates stumbled at the order and fell into a police officer. Sgt. L. C. Smith apparently mistook Cates’s stumble as a lunge for the officer’s pistol. Smith responded by punching the elderly man twice in the face. Cates wasn’t permitted to use the bathroom during the search, causing him to urinate on himself. Both Cates and Capps were also strip-searched. No drugs were found.

Catherine Capps later died from health maladies her family says she incurred during the raid. She was never charged with selling crack cocaine to the informant because, according to prosecutors, trying her would have required them to release the informant’s name. Subsequent investigations conducted by the Durham Police Department, the FBI, and the local district attorney found no wrongdoing on the part of police.

About six months prior to the Capps/Cates raid, the city of Durham had set up a citizens’ review board, in part due to community complaints about other allegations of excessive force on the part of police. But like similar review boards in other parts of the country, the proceedings were often conducted in secret, complainants weren’t given access to witnesses or evidence, and laws regarding search warrants kept vital information sealed. When Capps’s family attempted to file a complaint with the review board, the board instituted a new rule denying a hearing to any complainant who had previously sought financial compensation from the city, and applied the rule retroactively. Though neither Capps nor her family had asked for compensation, Cates had, giving the review board cause to refuse to even listen to a complaint about the raid.

Moving outside of Raleigh, there was this horrific raid, which took place the same year as the News & Observer investigation.

On September 4, 1998 police in Charlotte, North Carolina, deployed a flashbang grenade and carried out a no-knock warrant based on a tip that someone in the targeted home was distributing cocaine. When police got inside, they found a group of men playing cards. One of them, 56-year-old Charles Irwin Potts, was carrying a handgun, which he owned and carried legally. Potts was not the target of the raid. He had visited the house to play a game of cards. Police say Potts drew his gun and pointed it at them as they entered, at which time they opened fire, killing Potts with four shots to the chest. The three men in the house who saw the raid say the gun never left Potts’s holster. Police found no cocaine in the home, and made no arrests. The men inside the house at the time of the raid thought criminals were invading them. “Only thing I heard was a big boom,” said Robert Junior Hardin, the original target of the raid. “The lights went off and then they came back on . . . everybody reacted. We thought the house was being robbed.” Despite Potts’s death, an internal investigation found no wrongdoing on the part of the raiding officers.

At about the same time, the police in Concord, a town of 57,000 people just outside of Charlotte, were on a pretty astounding run of botched raids. There was this, in 1995:

In May 1995, police in Concord, North Carolina, mistakenly stormed the home of Jeffrey and Phyllis Hampton. The Hamptons were relaxing at around 9:30 p.m. when police broke down the door, stormed the house with guns, and ordered the couple to the floor. Police realized their mistake after about a half hour of interrogation.

And then . . .

Three years later, Concord police would wrongly raid another home, that of Leonard Mackin, Charlene Howie, and their four children. Police burst into that home with guns drawn on the night of May 22, 1998, and ordered the family to the floor. After repeated pleas by Mackin to police that they had the wrong house, Detective Larry Welch recognized Mackin as a co-worker with the city and asked, “Leonard, is that you?” A confidential informant had given police the wrong address.

A year later, this:

In 1999, police in the same town shot 15-year-old Thomas Edwards Jr. in the back while he was on his hands and knees under orders from a SWAT team conducting a drug raid. Edwards and five other children, all aged 13–17, were at the house playing video games when police conducted the raid. Officer Lennie Rivera shot Edwards just below the hip when, according to an internal police investigation, “a sudden movement jolted his gun, causing him to tighten his grip on it and pull the trigger.” Police found a small amount of marijuana and cocaine at the home. Police Chief Robert E. Cansler said that his officers had done surveillance on the home an hour or two prior to the raid and that “at that time there were no indications of a group of children present.” Officer Rivera was found to have improperly held his finger on the gun’s trigger and was assigned to more training.

You could pretty easily string together a history like this for nearly every state in the country.

The Supreme Court acknowledged in 1996 that the knock-and-announce rule is part of the Fourth Amendment’s protection from unreasonable searches and seizures. But a decade later, the court removed the only real remedy available when police violate that rule.

The consequences of that decision were entirely predictable. Rights without effective remedies don’t remain rights for long.

UPDATE: An attorney in North Carolina sends video of what one of these “quick knock” raids looks like: