Accusing Jordan Silverman

A D.C. teaching assistant was accused of molesting up to 15 kids. Multiple law enforcement agencies cleared him. But his nightmare was just beginning.

Jordan Silverman still isn’t sure he wants me to write this story.

He isn’t sure if he wants me to publish his real name (I have), his photo (I have not), or the real names of his partner and kids (I have not).

Silverman says he wants to clear his name. But he fears for his safety. He also worries about the repercussions for friends who might defend him. “‘Lisa’ and I have no idea how to navigate this,” he says, referring to his partner. “We’re still figuring it out. I worry about the threats and the harassment.”

Between 2018 and 2019, Silverman was accused of sexually abusing as many as 15 children. (It still isn’t clear exactly how many accusations there were. ) The alleged abuse took place at a preschool operated by the Washington Hebrew Congregation (WHC), a large and influential synagogue near Glover Park, along Massachusetts Avenue in Washington, D.C. The accusations, along with claims that the synagogue covered up the abuse, spurred a frenzy of international media coverage.

“Overnight, I saw my name linked with the worst crimes imaginable,” Silverman says. “I was powerless to do anything about it.” Silverman’s home was repeatedly vandalized. He received threatening letters in the mail, and built up legal debt he fears he’ll never be able to pay back.

Today, at age 49, Silverman’s wavy, reddish-brown hair — his friends call it his trademark — is graying around the edges. His light beard skirts weary, deep-set eyes. He’s slender, but looks more drawn and fragile than fit. “I don’t eat much anymore,” he told me in a Zoom interview last year.

For 18 months, three law enforcement agencies thoroughly investigated Silverman. They went through every electronic device he owned, scoured his past, and interviewed friends and family up and down the East Coast. Then, the U.S. Attorney for Washington, D.C. and the D.C. Metro Police Department cleared him with an unusual, strongly-worded public statement: “After exhausting all investigative avenues, the universal determination of the investigative team was that there was insufficient probable cause to establish that an offense occurred or to make an arrest.”

It’s rare for federal prosecutors to put out such a statement — and it’s nearly unheard of for them to publicly state that they don’t have enough evidence for an arrest, much less a conviction.

But the statement didn’t persuade Silverman’s accusers. It only further infuriated them.

The very public, extremely salacious allegations against Silverman and WHC sit at the nexus of two conflicting narratives about power and sexual abuse. The first narrative is driven by the long and growing list of institutions and powerful people who have covered up the abuse of children and vulnerable people entrusted to their care. It’s a list that includes the Boy Scouts, U.S. Gymnastics, the BBC, the United Nations, and nearly every major religious organization. It includes the MeToo movement and, more recently, the Jeffrey Epstein scandal.

The second, contradictory narrative emerged in the 1980s and 1990s, when a nationwide panic over the occult and sex abuse produced a series of horrific false accusations. Teachers, daycare workers, parents, and grandparents were wrongly convicted and imprisoned on nightmarish allegations including sexually abusing children during satanic rituals, forcing children to have sex with animals, and sodomizing children with knives.

There was never any physical evidence to corroborate most of those allegations. There were no medical records documenting abuse. There were no bodies, and no dead or missing children. Most convictions were based largely or entirely on accusations that therapists and law enforcement officials had extracted from children. Some of those convictions are still being overturned.

“We think that when the system clears someone’s name, everything has worked the way it was supposed to. But it doesn’t restore those people where they were before the accusations. Not even close.”

Much of the media coverage of the accusations against Silverman tried to shoehorn the story into the first narrative, about institutional failure. But sociologists, therapists, and other experts who have studied the ritual sex abuse panic say it has all the red flags of the second one. The allegations against Silverman spread through the WHC community like a contagion. Over time, they increased in number, detail, and depravity even in the absence of physical evidence. As lawyers for the synagogue wrote in a court filing, the allegations were solely based on children’s accounts, which were “vague, varying and often inconsistent.” Some of these statements were recanted, as children later claimed they were joking, lying, or never made the accusations in the first place. According to the brief, “there are substantial concerns that the alleged statements were the product of loving and empathetic but nevertheless leading and suggestive questioning.”

There is one important difference between the allegations against Silverman and those made during the ritual abuse panic — Silverman was never charged. In this sense, one might argue that the system “worked.” Police and prosecutors took the accusations seriously. They conducted a long and thorough investigation. And when that investigation failed to produce any evidence, they declined to prosecute.

Yet both the accusers and the accused feel the system failed them. “Where is the protection for my child?” one mother wrote in an email to federal prosecutors after Silverman was cleared. “Why does it seem like you are protecting a predator and, for no reason, an institution that harbored a predator?”

As for Silverman, legal bills have left him with debt in the high six figures. He’s a former photographer and teaching assistant who is unlikely to make a living in either profession again. And he lives in a perpetual state of anxiety, waiting for the next shoe to drop.

“I applied for 150 jobs after the accusations went public, from bagging groceries to fast food,” he says. He’s now employed, but has asked that I not divulge where or how he managed to land a job. That’s how he lives now — carefully shielding what he reveals about himself, always worrying about what may follow if a new acquaintance, or friend, or professional contact Googles his name.

Most devastating, Silverman is no longer able to see his two sons. “If you asked me to name the one thing someone could do to Jordan that would hurt him most, that would be it,” says Maureen O’Dea, Silverman’s longtime friend. “Being a father is what he cherishes most in life. That has now been taken from him.”

All of this is why Silverman is so conflicted about seeing his story in print. “What if your article makes people angry all over again?” he asked me during one particularly frustrating crisis of confidence. “What if I lose my current job because of this? What if just one vigilante reads your article and decides to come after me? I have a life now. It’s a shell of what it once was, but it’s something approaching stable. Is trying to clear my name really worth the risk?”

Part One

Jordan Silverman was born in 1976 in a small town about an hour north of New York City. His childhood was happy, save for one formative event: his parents divorced while he was still in grade school. “It made me 100 percent more inclined to make sure I do whatever it takes to never go that route myself,” he says.

Life would have other plans.

Silverman eventually settled in Burlington, Vermont, and opened a photography business. Friends say Burlington fit the outdoorsy, socially conscious Silverman like a pair of Gore-Tex socks. He made his living in photography, but also dabbled in community organizing, sustainable farming, and violence intervention counseling.

“I wouldn’t say Jordan is a caricature of Burlington,” says O’Dea, who was Silverman’s housemate in the early 2000s. “I would say he is Burlington.”

When speaking about his own case, Silverman uses terms from the spheres of therapy and social justice. “I’m a straight, white, cisgender man,” he said when he first approached me at a criminal justice conference. “I have support networks that I’ve been able to fall back on. I’m aware of the privilege that comes with all of that. I know that if I didn’t have those advantages, I’d probably be in prison.”

“Jordan is the most empathetic person I know. Almost to a fault,” says Marc Richter, another longtime friend from Vermont. Richter himself is a therapist who has worked with victims of sex abuse. “I remember having breakfast with him at a restaurant once, and a parent at another table started disciplining his kid in a really aggressive way. I looked over and Jordan had tears in his eyes. That’s just Jordan.”

In 2005 Silverman met “Rebecca” on a dating app for Jewish singles. Within a couple months, Rebecca moved to Burlington from her home in Massachusetts. The couple moved in together and were engaged shortly after.

Friends thought they had moved far too fast. And indeed, the marriage was a struggle, almost from the start. “They had committed to this idealized life before they really got to know one another,” says Richter. “And unfortunately for Jordan, I think Rebecca realized early on that she just didn’t like him. She couldn’t stand him.”

“They weren’t a good match,” says O’Dea. “Jordan can be intense. A day with Jordan is getting up at 5 am to do a two-hour canoe paddle. Then eating granola on the beach. Then meeting up with friends to swim in the river. Then lunch, then a Circus Smirkus performance. Then flying a kite, and then watching a meteor shower outside until you fall asleep.”

Silverman’s friends say that Rebecca, on the other hand, didn’t go out much. “She was standoffish,” says Richter. “I think she found Jordan exhausting.” (Rebecca did not respond to my requests for an interview.)

After having two boys together, the couple divorced in 2012, and to the surprise and dismay of Silverman’s friends, Rebecca asked for sole custody. A Vermont court ordered 50/50 physical custody, instead. Rebecca would continue to fight for sole physical custody for the next 10 years. “She didn’t want Jordan in her life at all,” says O’Dea. “So she kept asking the courts to cut him off from the boys.”

In 2013, Rebecca got a job offer in the Washington, D.C. area. She asked a Vermont court for permission to move and to take her sons with her. She also again requested sole custody. The court again denied that, but it did allow her to move.

“Jordan was devastated,” O’Dea says. “He was the poster case for what a good dad should be. And I mean that literally. Burlington ran this campaign to encourage fathers to be more active in their kids’ lives. They picked Jordan as the ideal dad. So there were these posters all over town of Jordan smiling with his boys.”

Silverman decided he had to leave Vermont. “There was really no other option,” he says. “I had to be near the boys.” He closed up his photography shop, moved to D.C., and started a new life.

A couple years later, in 2015, Silverman had custody of his sons for New Year’s Eve, so he took them to Pennsylvania for a woodsy family retreat. There he met D.J. Jensen, the director of the preschool at the Washington Hebrew Congregation in D.C.

“We got to talking — about our kids, our jobs, about Jewish life in D.C.,” Silverman says. “I told her about my photography business. I had lined up a number of clients in D.C. with government agencies, colleges, and universities. But I really needed health insurance and a steady paycheck.”

After watching him with his own kids and hearing about his volunteer work at their preschool, Jensen asked Silverman if he had ever thought about teaching. “I hadn’t ever really considered it to be an option,” he says. “But I really love working with kids, so I was open to the idea.”

By the end of the retreat, Silverman was sold on the idea. He showed Jensen a letter of recommendation the director of his own kids’ preschool had written for him on an unrelated matter. When he returned home, Silverman applied, interviewed, and was hired as a teaching assistant at the WHC preschool. He would start work in early 2016.

Silverman’s quick hiring and lack of background in education would later be cited in court documents as evidence of his guilt. “I guess some people found it suspicious that a guy with no teaching experience would take a job at a preschool,” he says, “as if only a predator would take that sort of job. I needed health insurance. I needed to be near my kids. The job let me continue doing photography on the side. But also, I like working with kids. I didn’t think that was something I needed to hide or apologize for.”

If Silverman was a perfect fit for Burlington, he was a conspicuous outsider at WHC. The synagogue is perhaps the most prestigious and well-known Jewish congregation in the D.C. area, and one of the largest and oldest in the country.

“Washington Hebrew is the Mercedes of D.C.-area synagogues,” says “Francine,” a former teacher at the preschool who also sent her own kids there. “Jordan didn’t have a lot of money, and he was the only male teacher. He was crunchy, goofy, affectionate, and sweet. He stuck out, and I think some parents thought he was weird. But the kids loved him.”

Silverman’s friends say he can be quirky, and sometimes has issues with boundaries. Some speculate that those traits might be why he was viewed with suspicion by parents who didn’t know him.

“He sometimes called me baby,” says Richter, Silverman’s longtime friend in Vermont, who sent me a couple of emails in which Silverman used the term. “He’d use it with waitresses, kids, his clients. I finally told him after MeToo that you just can’t do that anymore.”

“These are terms of endearment coming from him,” says O’Dea. “Jordan is sensitive. He wants to connect with you. I think a lot of men just can’t imagine using those terms with anyone other than their wives.”

Silverman’s habit of using terms of affection also came out in the accusations against him. In court documents and online forums, teachers and parents say he inappropriately called kids “honey” or “baby.”

“My mom always called me ‘honey’ growing up, so it’s just a word I came to use in my daily interactions with people,” Silverman says. “But a lot of teachers had nicknames and pet names for the kids. At some point, D.J. told us we needed to adopt best practices for addressing the kids. Those say you should just use the kids’ first names. So that’s what we did.”

Francine confirms that other teachers also often used pet names for the kids, but says some parents seemed particularly put off hearing it from Silverman, who was the only male teacher.

“This whole thing just seemed like a bunch of rich frat guys picking on a nerd,” says Jonathan Jeffress, Silverman’s attorney. “Jordan was this hippie from Vermont who didn’t fit in, and probably struck some people as a little weird. So after the first accusations, the rumors started to gain momentum. Then it all just spun out of control.”

Part Two

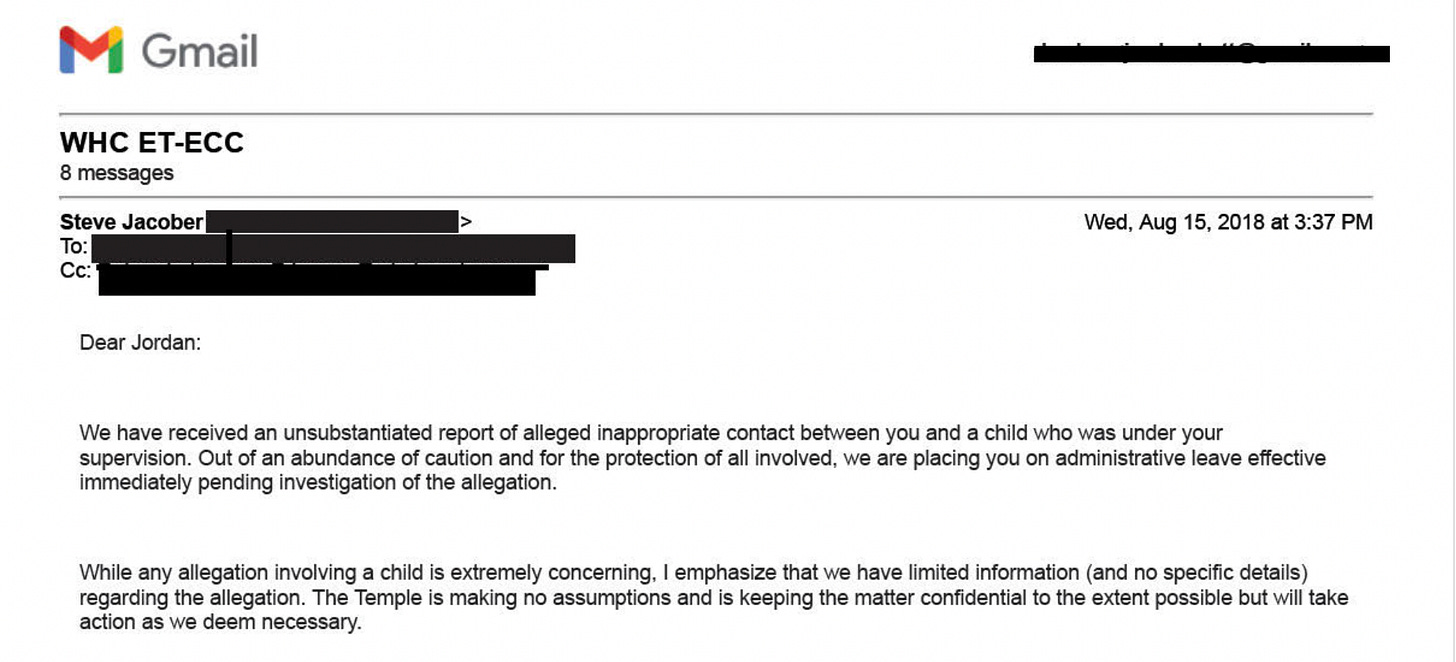

On August 15, 2018, as he was preparing for his upcoming fall class, Silverman received the email that would upend his life.

It came from the WHC executive director. “We have received an unsubstantiated report of alleged inappropriate contact between you and a child who was under your supervision,” he wrote. “Out of an abundance of caution and for the protection of all involved, we are placing you on administrative leave effective immediately pending investigation of the allegation.”

Silverman says he was stunned. Over the next several days, he sent a series of desperate queries asking for more information. What did they mean by “inappropriate contact?” Was this related to a recent incident in which he had separated two kids who were fighting? Did the incident involve students at the school or was this an accusation about his own kids? He’d just gone through a messy divorce. Had his ex-wife made some accusation? Could he meet with the school as soon as possible to clear this up?

He got no reply from the school. On August 19, he received a voicemail from a D.C. Metro Police detective informing him that he was now the subject of a criminal probe. The FBI and U.S. Attorney’s Office would join that investigation.

On August 28, the D.C. Child and Family Services Agency (CFSA) opened its own investigation. Child services offices aren’t police agencies or courts, but their investigators often work in cooperation with law enforcement, and can refer cases to police if there’s evidence of criminality.

They also have incredibly difficult jobs. These agencies are often hobbled by tight budgets, staffing shortages, and heavy workloads, and are under tremendous pressure. If an investigator erroneously exonerates someone of abuse, they’re subjecting that person’s future victims to a lifetime of trauma. But wrongly substantiating allegations inflicts significant harm as well. False allegations can ruin lives even if the case never gets to the point of criminal charges. And if the accused is a parent, false accusations can break up a family.

Despite these high stakes, because they don’t criminally charge people, D.C. CFSA investigators use a lower standard of evidence than law enforcement. At the same time, political pressure and recent headlines can weigh heavily on how an investigator handles a complaint. There’s also the risk of overcorrecting from previous mistakes.

“People in child welfare have seen tremendous amounts of abuse and harm,” says Jessica Henry, a former public defender and the author of Smoke But No Fire: Convicting the Innocent of Crimes that Never Happened. “So when someone brings in allegations, biases kick in. There’s a danger of trying to prove the crime instead of investigating whether a crime was actually committed.”

The original allegations against Silverman are documented in a 16-page report produced by CFSA. Although the publicly available version is redacted almost in its entirety, the report makes clear that the CFSA investigator was assigned Silverman’s case, conducted all her interviews, reached her conclusions, and closed her investigation all in the same day.

According to the report, five different families accused Silverman of sexually abusing their children. But the redacted report only includes details about one. “Robert” and “Alison,” who were the first parents to come forward, said that Silverman had abused their daughter “Jenny.” (I am not using their real names, both to protect Jenny’s privacy, and because there will be a separate, unproven suggestion of abuse. Alison and Robert did not respond to my questions or my request for an interview.)

According to the report, Jenny told her parents that “Mr. Silverman would take her and her friends to the bathroom and play a silly game, he then would tell them to pull down their pants and underwear, and he then would pull at their vagina and make a farting sound with his mouth.” The report notes that Jenny told her parents this happened “several times.”

The specific allegations from the other four accusers are redacted. So isn’t clear whether the investigator interviewed the children themselves or just their parents. It also isn’t clear how those interviews were conducted or whether the investigator spoke with anyone other than the families — such as school staff, doctors, or therapists.

The redacted report does show that the CFSA investigator attempted to interview Silverman. He declined. Silverman says that he was desperate to clear up whatever misunderstanding had caused all of this, but his attorney advised him not to talk to CFSA.

Criminal defense lawyers generally advise people under investigation not to speak to police. But “Lana,” a D.C.-area sex abuse investigator who is familiar with the case — and who has worked both with law enforcement and defense attorneys — says it’s different with child services. “If they only have some questionable accusations and there’s no other evidence, sometimes all they need is a denial” to dismiss the allegations, she says. “But if you don’t talk to them, all they have are the accusations. And if there’s no evidence pushing back, they have to substantiate.”

According to the CFSA website, to “substantiate” an allegation means that there is “credible evidence that a child was abused or neglected and the person in question was the maltreator.” In Silverman’s case, the investigator concluded that four of the five allegations were “substantiated” while the fifth was “inconclusive.”

The CFSA would be the only investigative agency to implicate Silverman. Everything that followed would stem from that report.

Security camera footage of an incident on December 25, 2018. At around 2:00, a figure emerges from a white car and begins beating Jordan Silverman’s car with a club

The investigator in charge of Silverman’s case is no longer with the CFSA. When I called her for comment, she deferred my questions to her former office. I sent the D.C. CFSA a list of 12 questions. The office’s answer to nearly all of them was the same: They said I was seeking information that “pertains to an investigation and cannot be disclosed.”

The CFSA also emphasized that it cannot disclose information that “identifies individual children reported as or found to be abused or neglected.” But when I got a copy of the CFSA report through a third party, who had obtained it through an open records request, something immediately jumped out. The office had redacted almost all of the details of the allegations. But it had not redacted the real names of the alleged victims.

This was an inexplicable oversight. “Really sloppy,” says Mark Schamel, a defense attorney who has litigated sex abuse cases in the D.C. area. “The identity of the alleged victims is the most important thing you’re supposed to keep sealed. If they can’t even do that when complying with an open records request, I wouldn’t put much faith in the rest of that investigation.”

Silverman had also requested his own copy of the report. His copy also included the names of his alleged victims. CFSA had inadvertently sent an accused sexual abuser the names of the children who had accused him.

In my communications with CFSA, the only aspect of the case the office wanted to address was the fact that they had mistakenly released the children’s names. Shortly after my initial phone call with CFSA, the office sent Silverman a letter demanding that he destroy his copy of the report, and that he instruct anyone to whom he had sent it to destroy their copies as well.

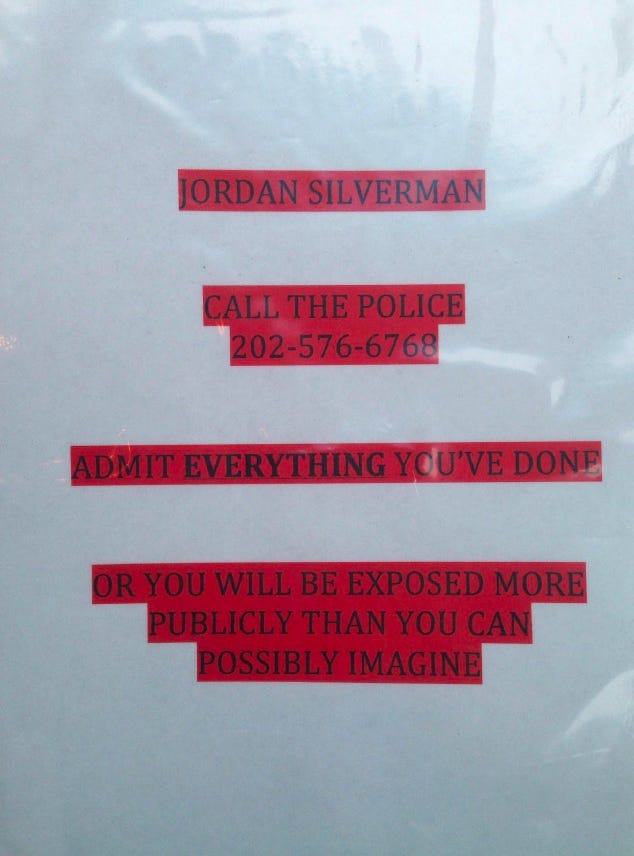

A couple days after the CFSA investigation closed, Silverman spent the night at Lisa’s. When he got home the next morning, he found a note taped to his door. It read:

“JORDAN SILVERMAN CALL THE POLICE, ADMIT EVERYTHING YOU’VE DONE OR YOU WILL BE EXPOSED MORE PUBLICLY THAN YOU CAN POSSIBLY IMAGINE”

Part Three

Jenny — Robert and Alison’s little girl — had been struggling for awhile. According to court documents and people familiar with the allegations, WHC staff began to document “regressive,” “violent,” and “distant” behavior in the girl starting in October 2017.

The problems persisted and in March 2018, Jensen, the school administrator, asked Robert and Alison to meet with her to discuss her concerns.

A month later, in April, Jenny turned in an alarming art project. As WHC attorneys would later recount in court filings, Jenny “drew a picture of a snake between ‘daddy’s’ legs that ‘tickled’ the whole family.”

School officials are required by law to report any reasonable suspicion of abuse, so WHC immediately notified CFSA.

It isn’t clear if CFSA ever investigated the art project. The report on the accusations against Silverman suggests they may have. But the details are redacted.

While WHC was required to report Jenny’s art project to authorities, it is not proof of abuse, by her father or anyone else. The only thing that is clear from publicly-available documents is that a few months later, in the summer of 2018, Robert and Alison reported their own complaint to the CFSA, accusing Silverman of molesting Jenny. And according to multiple sources familiar with the accusations, Robert and Alison also began warning other WHC parents that they suspected Silverman was a serial abuser.

Silverman had actually met the couple several years earlier, in 2014, at a different synagogue they all attended, long before he took the job at WHC. They were a power couple in the metro area. Robert was the CEO of a marketing and communications firm. Alison was an acclaimed interior designer.

After he first met Alison at the synagogue, Silverman messaged her over Facebook and the two arranged for Silverman and his boys to come over for dinner and a playdate with the couple’s two sons. (Jenny was just an infant at the time.) Silverman thought the evening went well. The couple’s boys were about the same age as his. He thought he’d made a much-needed social connection for himself and his kids as he made his new life in a new city. He would later learn that the couple recalled the evening quite a bit differently.

In 2016, two years after the dinner and playdate, Robert and Alison enrolled two-year-old Jenny at the WHC preschool. She was placed in the class where Silverman would be working as a teaching assistant. Then, prior to the start of the new term, a school official pulled Silverman aside with an unusual instruction: he was told not to change Jenny’s diaper. Silverman can’t say for sure if the instruction came directly from Jenny’s parents, but Jenny was the only child for whom it applied.

“I thought it was odd,” he says. “But I was also the only male faculty member at the school at the time, and men are pretty rare in childcare. It bothered me, but I just figured the parents had some outdated beliefs about gender roles. So I let it go.”

Jenny was in Silverman’s class for about six months. By the time her parents reported him to CFSA in the summer of 2018, Jenny hadn’t been in his classroom for more than a year. However, he would have occasionally supervised activities she participated in outside her main classroom.

Silverman says that, at first, he had no idea who had accused him. It become clear about a month later, in September 2018. By then he was in a relationship with Lisa, who he had met on a dating app the year before. Lisa had two kids of her own and one of them ran cross country.

On Saturday, September 22, Silverman and his two sons had planned to meet up with Lisa at a high school cross county meet, along with Silverman’s brother, who was visiting from California. But before they arrived, Lisa noticed that a man appeared to be following her as she moved around the course to cheer on her son. When Silverman, his brother, and Silverman’s own sons showed up, the man began to loudly accuse him of being a “pedophile.”

Silverman recognized the man as Robert, Jenny’s father. One of Robert’s own children was competing for a rival school.

Silverman and Lisa decided that he and his boys should leave. As they headed toward the car, Lisa saw Robert talking to a security officer and pointing at Silverman. “I felt like I needed to intervene,” she says. “We had our children there. I didn’t really know what he was capable of.”

“These kids were interviewed over and over. And for the first several interviews, they didn’t make any allegations against Mr. Silverman. But the parents kept pushing.”

Lisa walked over to Robert and the security guard. She told them that they were there with their children, and asked Robert to let Silverman leave without further harassment. “He just refused,” she says. “He asked if I was ‘the mother or the girlfriend,’ and said that my children and Jordan’s boys and everyone there needed to know that Jordan was a pedophile.”

Robert then began to quickly move toward Silverman in the parking lot. Lisa texted Silverman’s brother. “You’ve got to get him out of there,” she wrote. “That man is looking for him.” After a tense couple minutes, Silverman’s brother texted back — “exited.”

“At that point it was clear who had accused me,” Silverman says. “Or at least who the main accusers were.”

Robert and Alison had been cooperating with police. On October 7, 2018, in an ongoing email correspondence with the D.C. Metro Police Department detective investigating the case, Robert copied Silverman on one of his replies, likely inadvertently.

In the email, Robert references the dinner he and Alison had with Silverman four years earlier. He calls it “bizarre.” He writes, “Before that dinner, he had VERY persistently messaged [Alison] over Facebook attempting to make plans involving all our kids. At the time I thought he probably was interested in my gorgeous and brilliant wife, but in hindsight, he may have just been trying to earn our trust as parents of a young girl.”

Silverman showed me the Facebook messages in question. In contrast to Robert’s characterization, Silverman comes off, at worst, as someone perhaps overeager to make new friends. After the dinner, he doesn’t message Alison again for eight months, when he asks if she’d be interested in getting their families together for New Year’s Eve. She replies that they already have plans. According to Silverman, the two did not correspond after that.

In his email to the detective, Robert also includes a link to an ad Silverman took out seeking a tenant to rent his basement apartment. The ad featured photos of the home, which Robert describes as “full of kids drawings.” By Robert’s description, this supported his allegation that “drawings and games may have been involved” in Silverman’s abuse of Jenny.

“Those were drawings my kids and Lisa’s kids had made,” Silverman says. “He thought it was suspicious that we hung our own kids’ art on the wall.”

Robert’s email continues with a vigilant tone. “Our family will cooperate with you, and the AUSA, on any grand jury needs,” he writes. “We will not waver, or change our mind, and can be relied on from now until the time justice is served.”

Robert ends the email with a particularly puzzling proposition: He offers himself up as an informant. “Regarding wearing a wire, I would do so without hesitation if you decide it might help,” he writes. “Because Jordan has asked me to hire him in the past, I feel I could have a disarming conversation with him about freelance photography gigs. In my professional career, I sometimes wear the hat of a media trainer, and I think I could do a decent job of role playing in this type of situation.”

The suggestion that he could strike up a “disarming conversation” was especially odd. Just days earlier, Robert had confronted Silverman at the cross country meet and loudly accused him of being a pedophile.

“I think my reaction that email it was similar to my reaction to the email telling me I was suspended,” Silverman says. “It was just a surreal, out of body experience. It washes over you in this way where you no longer feel like these things are happening to you, but you’re witnessing them, like you’re reading a book or watching a movie.”

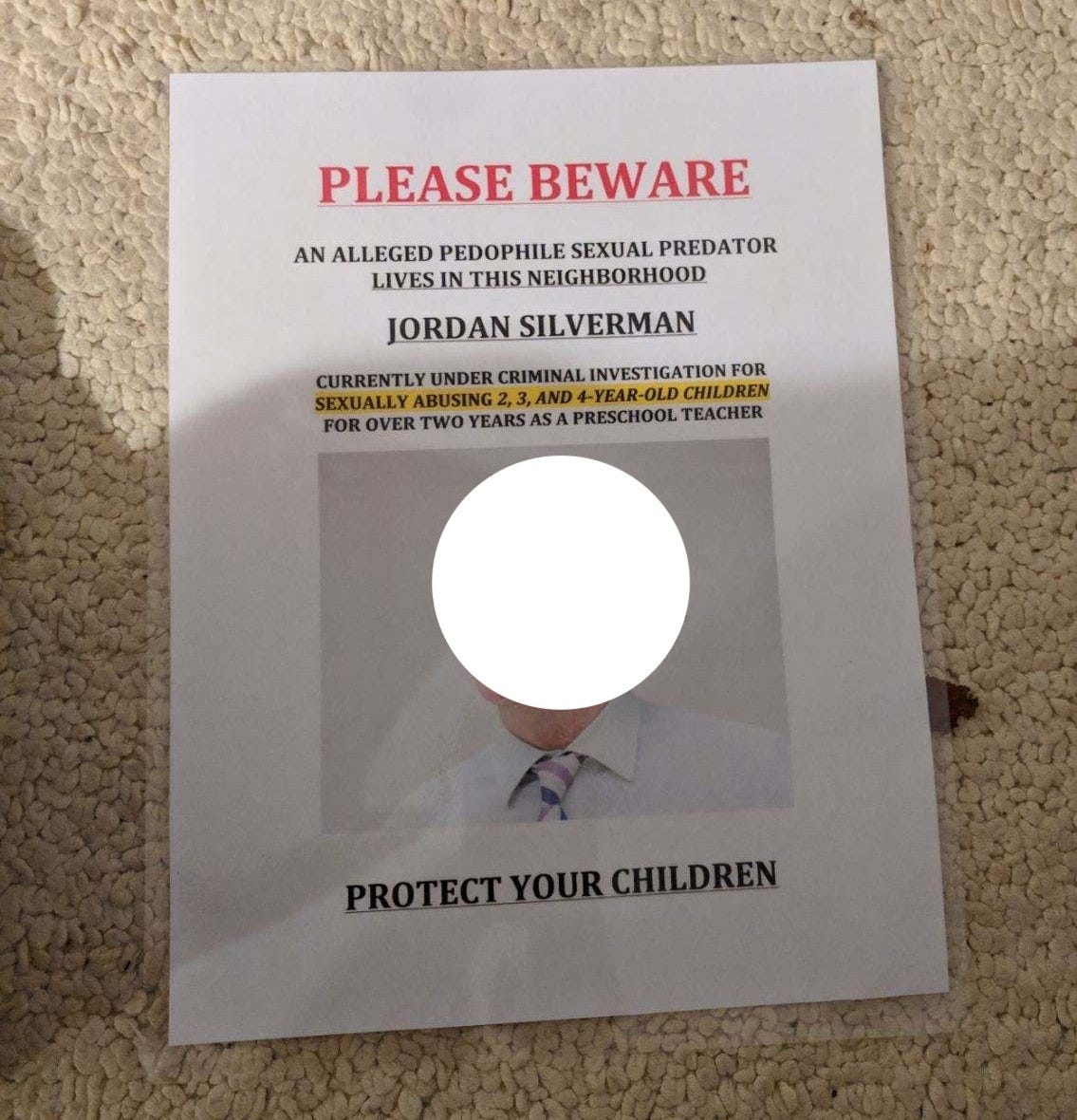

A few weeks later, on Halloween night, someone scattered dozens of flyers on Silverman’s lawn. They included his name and photo, with a warning to neighbors to beware of the predator who had been accused of “sexually abusing 2, 3, and 4-year-old children.”

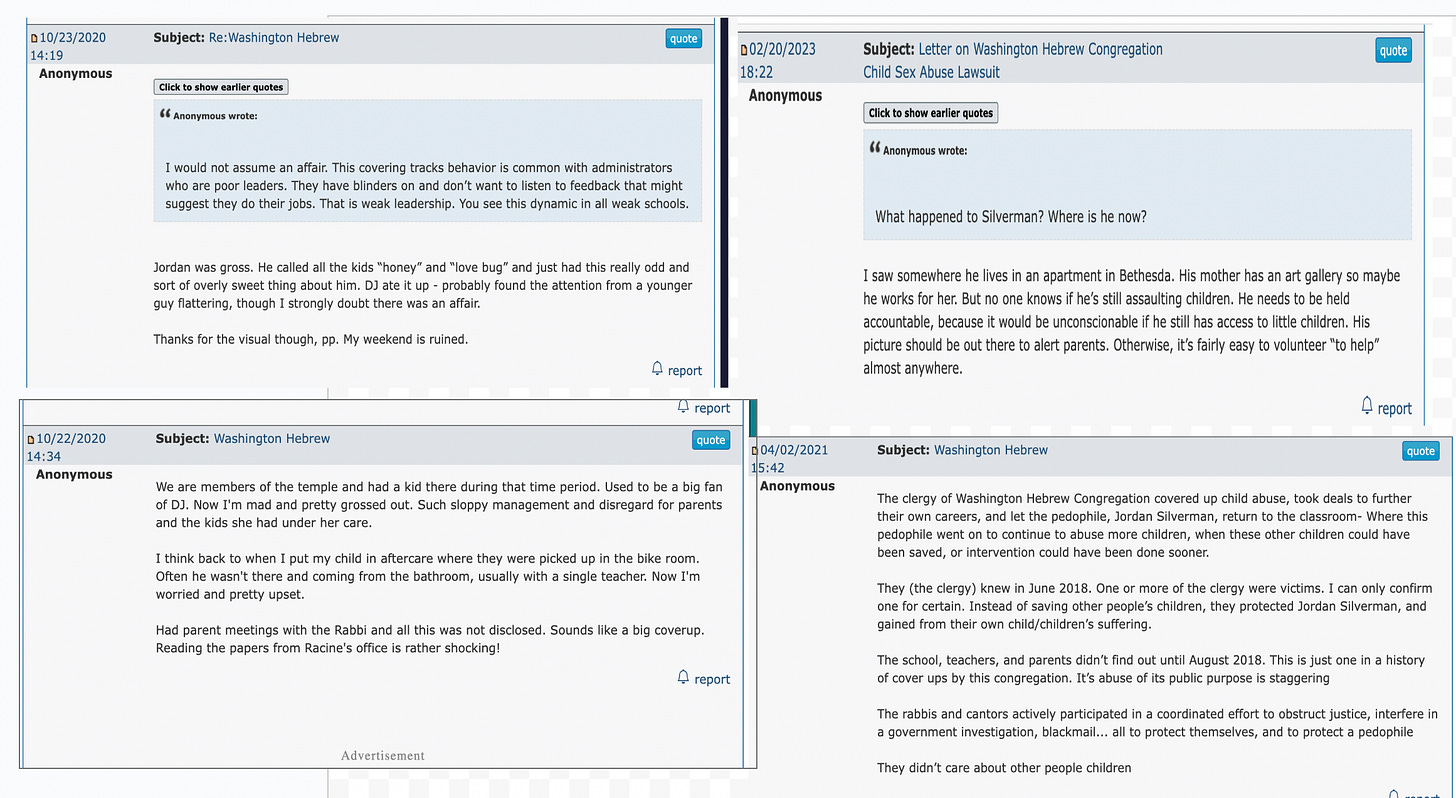

The accusations then began to pop up in online forums, particularly on Facebook and the forum DCUrbanMom.com. “They were accusing me of horrible things,” Silverman says. “There were threats and people posting that if the police don’t arrest me, someone ought to take matters into their own hands. Any posts that defended me were deleted.”

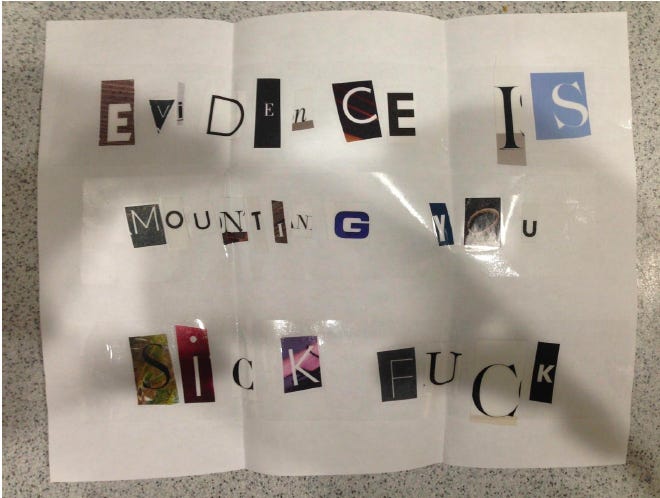

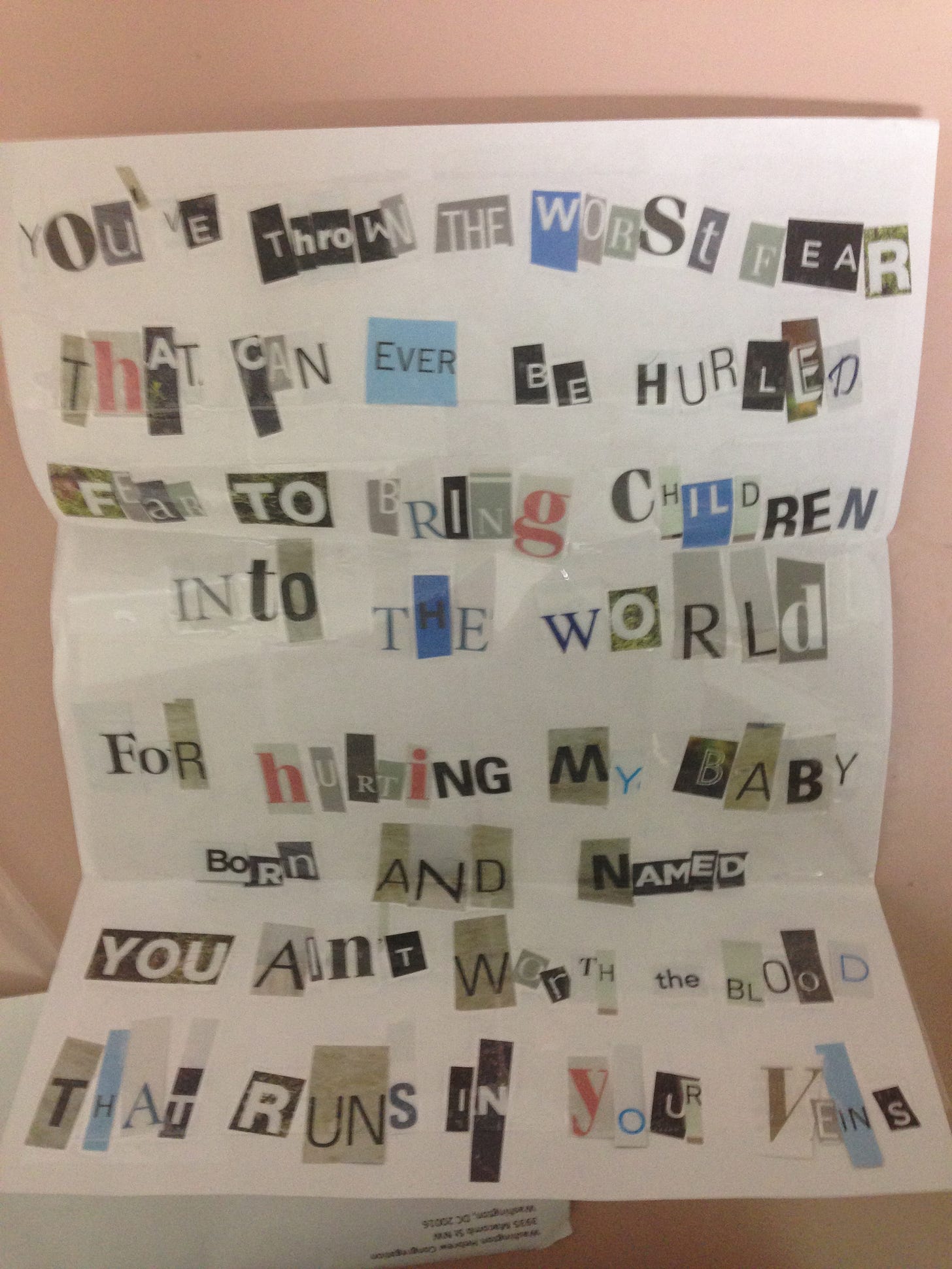

In late 2018, the harassment escalated. Silverman received threatening letters spelled out with characters cut from magazines, similar to a ransom letter. One read, “Evidence is mounting you sick fuck.” Another included the line, “You aint worth the blood that runs in your veins.” In mid-December someone spray painted “child rapist” in front of Silverman’s home — the first of several such incidents. On Christmas night, his security camera caught a man smashing out the window and taillight of his car with a club. A month later, someone busted the back window and one of the headlights.

In late January 2019, on the advice of his attorney, Silverman documented 11 incidents of harassment and sent them to local police. During one spray painting incident, he was actually able to take a photo of the perpetrator’s license plate. He would later send that information to a private investigator, who found that the car had been rented by a father whose kids attended WHC — and who was friendly with Robert and Alison.

Silverman shared all of this with police, but he also didn’t want to press charges, for a couple reasons. First, because of the WHC criminal investigation, his attorneys had told him not to speak with law enforcement about the allegations against him. And he couldn’t really explain the harassment without getting into the allegations.

This resulted in extended email chains in which Silverman told police he feared for his family’s safety, and begged for them to intervene, while the police showed increasing frustration as Silverman refused to talk to them in person.

But Silverman says he also understood why the parents were angry. He didn’t want anyone to be arrested, he says. He just wanted the harassment to stop.

“I guess I was trying to walk a line,” he says. “I didn’t even want the people doing this to me to be charged. I even sympathized with them. I have no idea what I’d be capable of if I thought someone had hurt one of my kids. But I was also living in fear. You start to panic at every snapped twig. Every time a strong breeze rattles a window.”

Security camera footage from December 11, 2018. At around 4:30 a figure in a reflective vest spray paints allegations of child sexual abuse on the sidewalk in front of Jordan Silverman’s home.

Part Four

On April 4, 2019, Silverman was awoken just before dawn by a team of Metro PD officers and FBI agents. When he saw the SWAT team gathered on his porch over a security camera, he rushed downstairs and opened the door. He was just in time. They had a battering ram at the ready.

The officers stormed inside. They handcuffed him and had him stand outside while they tossed his house. The police confiscated every electronic device he owned — his cell phone, computers, and cameras, along with memory cards and hard drives filed with tens of thousands of photos. He was not arrested. It would be months before he got any of his property back.

Meanwhile, investigators also went to Vermont to interview Silverman’s old friends. Richter, his therapist friend, had agreed to store several boxes for Silverman when he left Burlington. The boxes were filled with additional hard drives, photographs, and memory cards. Those were all confiscated. “The only photo I remember them asking me about was one he’d taken of his own kids in the bathtub,” Richter says. “It was a cute photo. His kids were young, there were bubbles everywhere.”

Silverman says he still expected the investigation to clear him, and hoped he could get his photography business up and running again once the police had returned his equipment. But that was not to be.

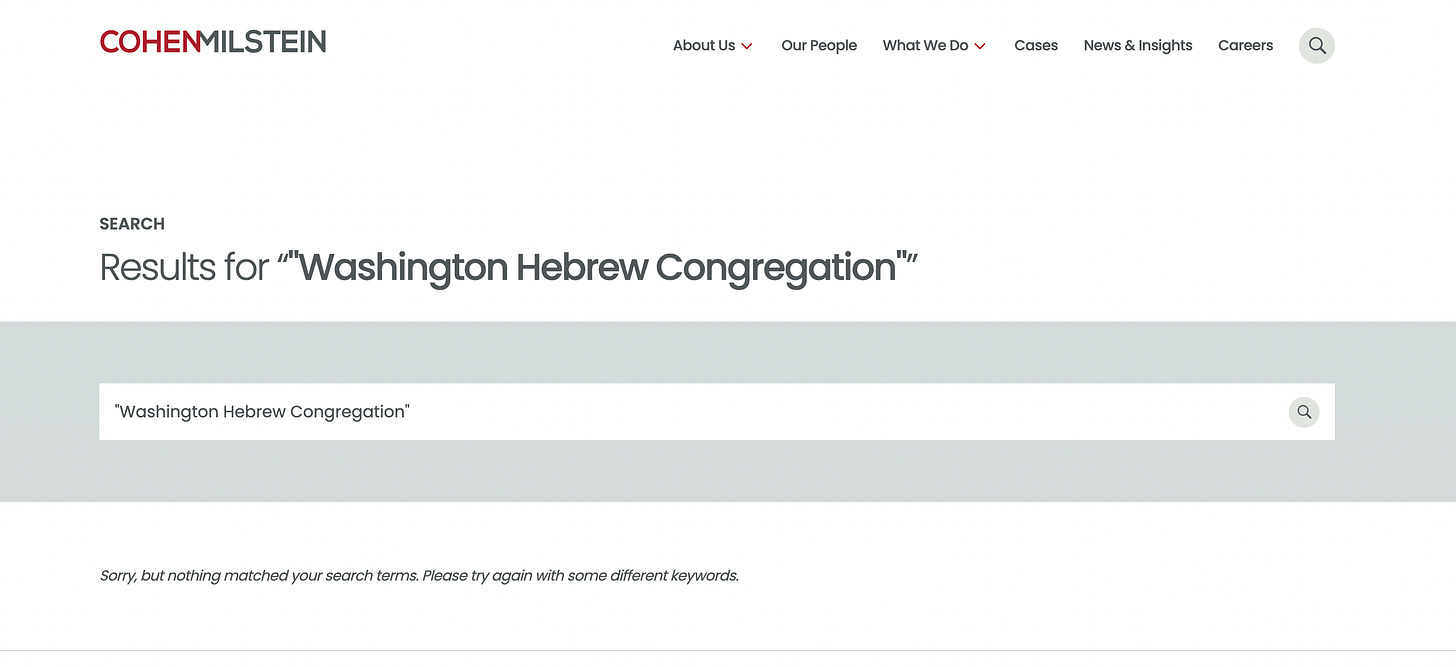

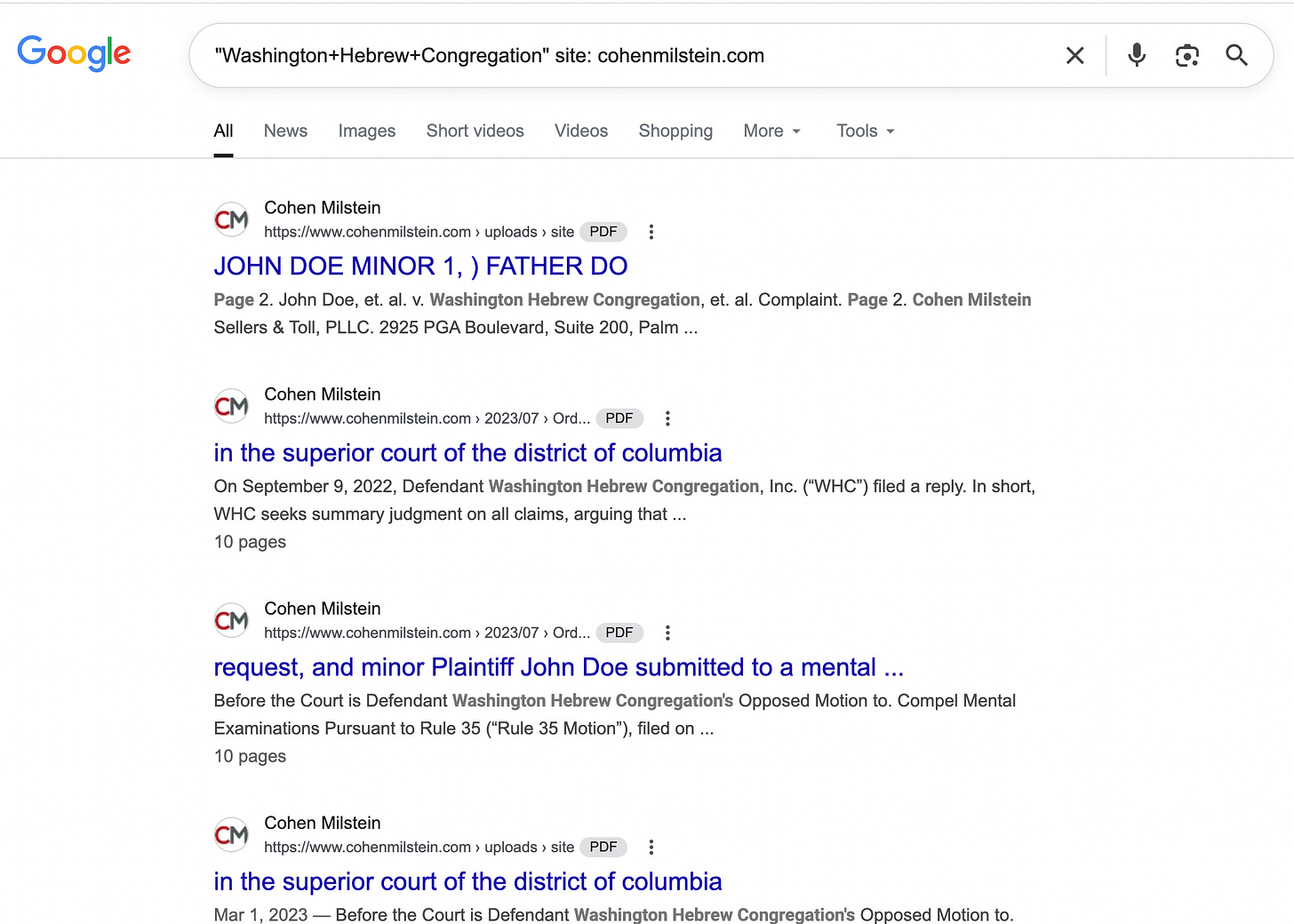

Eleven days after the raid on his home, Silverman received a call from a Washington Post reporter. A group of parents had filed a lawsuit against WHC, and they had hired the law firm Cohen Milstein to represent them. According to the lawsuit, eight families claimed that Silverman had sexually abused their kids, and the number of alleged victims could be as high as 15. The parents weren’t suing Silverman, they were suing the school for allowing him to abuse their kids. The reporter wanted to know if he had any comment.

Cohen Milstein has an entire division devoted to civil litigation related to sex abuse. The firm is also politically connected. It regularly partners with state attorneys general on public interest litigation — including with the office of the D.C. attorney general. As Silverman would quickly find out, the firm also has a deft public relations team.

Because Silverman hadn’t been criminally charged, the Post reporter agreed not to use his name. Other outlets, like the DCist, also didn’t publish his name. But the Post article did link to the lawsuit itself, and that used Silverman’s name numerous times.

Soon the Daily Beast, CNN, USA Today, the Forward, and other outlets ran their own stories. Those outlets did publish Silverman’s name. He was now internationally known to be a man accused of sexually abusing children. “Overnight, I was a pariah,” he says. “My life as I knew it was over.”

The Daily Beast article included several quotes from Michael Dolce, the Cohen Milstein partner who led the lawsuit against the synagogue. Dolce claimed that when several parents first told the school they thought Silverman was abusing kids, Jensen, the preschool director, told them they were “sick.”

Jensen “never investigated any claim against Silverman, never restricted his access to children, and never even reported the claims to city officials,” Dolce told the Daily Beast. “This man performed horrible and significant sex crimes against small children and the people that were supposed to protect them turned a blind eye.” The article included no quotes from Silverman’s attorneys. It seemed to take his guilt as a given.

Many of the court filings in the parents’ complaint are sealed. The documents I have been able to obtain allege that he committed “depraved” acts of sexual abuse, but don’t go into specifics. However, some of the details have come out in subsequent lawsuits, media outlets, and public forums. One of the more serious allegations was that he took explicit photos of children. But again, police found no evidence of this on his cell phone cameras, or any of the other equipment they confiscated.

As for the other details, many amounted to behavior his accusers considered suspicious. For example, Silverman took the kids on hikes and nature walks, which were characterized as an effort be alone with them outside the presence of other adults. There were allegations that he often left the classroom for long periods of time, and was sometimes unreachable over the walkie-talkies that teachers used to communicate.

Silverman says he was horrified as he saw the number of accusers increase from the original five to as many as 15. But he also says this should have made the allegations increasingly difficult to believe. “The school was always a busy place,” he says. “There are security cameras. There are always people coming and going. I can’t imagine the bathrooms were ever empty for more than a few minutes at a time. The idea that someone would be able to abuse children in there without anyone else seeing or hearing it is just absurd.”

“I heard about him being in the bathroom a lot,” says Alex Bailie, one of the few other men to work at the school, and whose tenure slightly overlapped with Silverman’s. “The guy was always so energetic, I just assumed he was off doing cocaine.” (Bailie seemed to be joking, and Silverman says he has never used cocaine.)

Former WHC teachers confirmed to me that the school is busy, heavily surveilled by cameras, and that there was regular traffic in and out of the bathrooms. Francine, the former teacher who also sent her own kids to the preschool, said she had heard the accusation that Silverman was gone for long periods of time. “But the people making them never bothered to talk to him,” she says.

She offers a possible explanation for his absences. “We weren’t allowed to look at our cell phones in the classroom,” she says. “So the bathroom was really the only place you could check your texts and email. Jordan was going through a bitter custody dispute at the time. He and his ex-wife were always bickering about setting up his visitation with his boys. That’s why he’d be in the bathroom.”

I also asked Francine what she made of the accusations from Jenny’s parents about Silverman making “fart noises” and pulling at her vagina. “Oh, wow,” she said. “That just shows how easy it can be to take something a kid says out of context. I changed diapers in those bathrooms. When you’re changing a kid who isn’t your own, you’re just trying to distract them long enough to get through it. You’re singing songs. You’re making faces. So yeah, I could see making fart noises. As for the vagina thing, you have to wipe the kids clean. So of course you’re wiping their privates.” The allegation was especially puzzling with respect to Jenny because Silverman had been told not to change her diaper — an instruction Francine says he followed.

As for the walkie-talkies, Silverman showed me emails he sent to Jensen to complain about the devices. He says he was concerned that teachers often left them lying around instead of charging them, so the batteries would die. “It was an issue,” he says. “No one was easily reachable with the walkie-talkies.”

As more time passed, the accusations against Silverman increasingly started to resemble the panic over ritual sex abuse.

According to the lawsuit, for example, some teachers said they had complained about Silverman to Jensen — in particular about him being unreachable by walkie-talkie, or being alone with the kids. But Jeffress, Silverman’s attorney, says the school had no record of any such complaints until after the parents’ accusations came out. (Of course, Silverman’s accusers say that’s because Jensen and other administrators failed to document them.)

Jessica Henry, the former public defender and author, says that once accusations are public, “You often see that sort of piling on. Everyone wants to look like they were on the right side all along. People start to remember incriminating details. But our memories can be deceptive.”

People who have studied these cases say the mounting number of accusers is a red flag. The five families who accused Silverman in the initial CFSA report had grown to eight by the time the parents first filed their lawsuit — and the lawsuit itself suggests as many as 15 families. One D.C.-area defense attorney, who isn’t directly involved in the case but is familiar with the investigation, says there “was definitely an effort to pressure other parents into accusing him.”

Mary DeYoung, former head of the sociology department at Grand Valley State University, has written extensively about the sex abuse panic cases in the 1980s and 1990s. “The first accusation often comes from a parent who may be overprotective or has a child who is having some behavioral issues,” DeYoung says. “Then word starts to spread. The first step toward confirmation bias comes when the parents start calling one another. Other parents then start looking for behavioral issues in their own kids — things like bedwetting, acting out, nightmares.”

Those problems could have any number of causes, of course. But DeYoung says fear can make parents unite behind a common threat. “It becomes self-reinforcing, particularly in tight social groups. If you’re a parent and someone tells you that five other parents say something happened to their child, it can be very difficult to separate yourself from the consensus — to be the one who says ‘No, nothing happened to my kid.’”

In that sort of panicked environment, well-intentioned parents may unwittingly suggest abuse that never happened while questioning their children. “In the context of sex abuse allegations, once a concerned caregiver or investigator says, ‘Did anyone touch you?’, children may adopt that language and parrot it back in an effort to please or accommodate,” says Henry. “I’ve even seen cases where parents will reward the kids — ‘Tell me what happened and I’ll give you an ice cream.’ But it doesn’t need to be that explicit. Kids will often just say what they think a parent or authority figure wants to hear.”

Due to the various court orders and legal protections for the privacy of children who allege abuse, none of the experts who are familiar with Silverman’s case were willing to speak for attribution about the details of the accusations. But several were alarmed enough to speak without attribution. “These kids were interviewed over and over,” says one psychiatrist who consulted on the case. “And for the first several interviews, they didn’t make any allegations against Mr. Silverman. But the parents kept pushing. They were all sent to the same couple therapists, who both used methods that were incredibly invasive and suggestive. Then, once rumors started to spread, other families came forward. It was a mess.”

“Two to four years old is a highly suggestible age,” says Lana, the metro-area sex abuse investigator. “Children that young need and want to provide information that they perceive the parent wants to hear. It’s very easy for a well-intentioned parent to subliminally reward the child for confirming their suspicions. They’re absolutely trying to do the right thing. But at that point the parent has already shaped the child’s narrative before the first forensic interview.”

The lawsuit and subsequent media coverage disabused Silverman of any hope that the accusations would be resolved anytime soon. His photography clients, which included several government agencies, quickly dropped him. His own synagogue sent a letter to its members that mentioned him by name. His boys’ school told him he was no longer permitted to set foot on campus.

Security camera footage from an incident in March 2019. At around 1:05, someone throws paint on the porch and front door of Jordan Silverman’s home.

Part Five

Neither Silverman’s ex-wife nor his own boys have ever accused him of any type of abuse. But the WHC accusations would derail his efforts to remain a part of their lives.

Silverman and Rebecca’s relationship grew more contentious in the years after he moved to the D.C. area. Prior to the WHC allegations, Rebecca had filed for sole custody several more times, and each time the courts ruled in Silverman’s favor, preserving the 50/50 arrangement.

According to Silverman, his friends, and court filings, Rebecca frequently violated those terms. “She would cut the boys’ visits short,” says O’Dea. “Or she wouldn’t respond to his calls or emails so he couldn’t schedule them at all.” These claims are supported by court documents.

Silverman says he could only enforce the visitation agreement by going back to court to request a contempt order. And he had to pay a lawyer every time he did.

After the news broke about the allegations against Silverman, Rebecca went back to court to ask for a protective order. In response, the judge reduced Silverman’s visitation to 4-6 hours per week. Those visits would also have to be attended by a court-approved chaperone, whose fee Silverman would have to pay. The protective order would remain in place until and if Silverman was cleared by the criminal investigation.

CFSA also opened a separate investigation into whether or not Silverman had abused his own boys, which is standard practice in such cases. That investigation closed at the end of October 2018, and found no evidence of abuse. But the finding wasn’t enough to revoke the protective order.

The visits became increasingly difficult. In April 2019, Silverman’s sons started texting him news articles about the allegations. The protective order prohibited him from discussing the case with them, so he couldn’t respond. Silverman and Lisa say his sons grew hostile toward him, and this is reflected in the reports filed by the visitation monitors. A therapist would later tell Silverman that the boys had become obsessed with reading about his case online, which was significantly harming their mental health. Though both Silverman and Rebecca were prohibited from discussing the charges with the boys, it would later come out in court documents that her new partner had told the boys their father “is a pedophile.”

Meanwhile, Silverman was building up significant debt. He was paying legal fees for his criminal representation and the custody battle, paying for a visitation monitor, and paying a private investigator. He had also lost his job, and the media coverage had made it impossible for him to find new work. “All you have to do is Google my name and it’s all there,” he says. “I’m not above menial work. But no one would hire me.” Silverman’s basement tenant moved out due to the vandalism and harassment, taking away one last source of income.

“Within a few months I had gone through my savings,” he says. “Then I maxed out my credit cards. Then we went through the money people had lent or given me.”

“I’ve lent him a lot of money over the years,” says Richter, Silverman’s friend in Vermont. “Or rather, I just gave him money. I never expected him to pay it back. I think a lot of his friends wanted to help.”

“I’m so lucky to have people in my life who would do that,” Silverman says. “But it’s also embarrassing. It’s embarrassing to owe large sums of money to your friends and your family.”

Silverman says all he could really do was wait for the criminal investigation to clear his name. He was hopeful that would happen quickly. He says he believed that the more they investigated, the more investigators would be convinced of his innocence.

In June 2019, federal prosecutors told Silverman’s attorneys that the investigation would be wrapped up within a month. That deadline came and went. They then said early September. That deadline passed, too. Frustrated, Silverman’s attorneys suggested he take a polygraph administered by a former FBI agent. Polygraphs aren’t considered reliable enough to be admissible in court, but police sometimes use them to guide their investigations. He paid for the polygraph and passed. But federal prosecutors said the questions weren’t specific enough. So in November 2019 he paid for another polygraph. He passed that one too. Yet the investigation dragged on.

“I think there was a lot of public pressure on investigators to throw the book at Jordan,” says Jeffress, Silverman’s attorney. “Some of these families are very influential, and you also had this powerful law firm pressuring everyone involved. But everything law enforcement was finding indicated Jordan hadn’t done any of this. I think the investigation went on so long because they knew there would be political fallout. They wanted to be able to say they left no stone unturned.”

Finally, in late January 2020, Jeffress got a call from D.C. Assistant U.S. Attorney Mark O’Brien, the prosecutor overseeing the investigation. O’Brien told Jeffress that an announcement was forthcoming, and advised him to tell his client, Silverman, to “be safe.”

A couple days later, O’Brien, the FBI, and Metro PD put out their joint statement clearing Silverman:

“After exhausting all investigative avenues, the universal determination of the investigative team was that there was insufficient probable cause to establish that an offense occurred or to make an arrest.”

It should have been a huge relief. Silverman had hoped that when law enforcement finally cleared him, there would be a flurry of media coverage vindicating him. Maybe he’d get an apology. Maybe the photography clients who dropped him would re-hire him and he could get his business running again.

None of that happened. Instead, the narrative in much of the media coverage was not that an innocent man had been wrongly accused, but that another powerful religious institution had exerted its influence to cover up sex abuse within its walls.

Under a headline calling the U.S. Attorney’s decision “unfathomable,” a particularly conspiratorial Daily Beast article extensively quoted angry parents, who accused the prosecutor of protecting a child predator.

One father told the publication that he angrily told O’Brien that abusers might as well target preschools, since the law didn’t seem to protect the kids who attend then. According to the father, O’Brien responded, “Well if you’re a pedophile, that’s a good place to start.”

O’Brien did not respond to my request for an interview, but two people who know him professionally say they couldn’t imagine him being so flippant about a sex abuse case.

The anger spilled over into online forums on Facebook and DCUrbanMom.com, where commenters speculated about where Silverman might live or work, and whether his mother owns a business in D.C.

While the parents’ anger was understandable, their allegations of a coverup were farfetched. All the public pressure — from politicians, the legal community, and the media coverage — was pushing the office to prosecute Silverman, not to exonerate him. “No federal prosecutor is going to conduct a 19-month investigation in which they discover that the truth is A, but then decide to go with ‘Not A,” says Mitchell Epner, a former federal prosecutor who worked on sex abuse cases. “You aren’t going to waste your resources like that.”

The parents were particularly upset that O’Brien had notified Silverman’s attorney of the decision not to prosecute before he had notified them. But there was a good reason for that — Silverman had been subjected to harassment, threats, and vandalism. With “be safe,” O’Brien seemed to be telling Silverman’s attorney to make sure his client was prepared for any backlash.

“I waited 18 months for law enforcement to clear me,” Silverman says. “When that day finally came, I had to leave my home and basically live in exile. And then the media just dragged my name through the mud again.”

Part Six

There was one other thing preventing Silverman from finally resting easy after law enforcement cleared him. In April 2019, CNN reported that D.C. Attorney General Karl Racine had opened his own investigation.

Racine, who was elected in 2015, has an inspiring personal story. He was born in Haiti, and his family fled to the U.S. when he was three to escape the terror of dictator François “Papa Doc” Duvalier. Racine was a star basketball player at Penn, worked at D.C.’s well-regarded Public Defender Services, and has a history of legal activism and public interest law. During Donald Trump’s first term, Racine and Cohen Milstein brought the lawsuit accusing the president of violating the Emoluments Clause.

In October 2020, ten months after Silverman was cleared, Racine concluded his investigation and announced that he had filed his own lawsuit against WHC and Jensen, the preschool director. He argued that the school had violated several regulations, and in so doing, had both failed to protect the preschoolers and misled the public.

Silverman wasn’t a party to the lawsuit, and the accepted legal practice in such cases is to avoid mentioning third parties by name, even those who have been accused of crimes. Racine’s complaint mentioned Silverman by name 43 times. He called Silverman a “potential predator,” and excoriated the school for leaving children in his care. This accusation presumed Silverman’s guilt. Racine’s complaint never mentions that Silverman had been cleared by three law enforcement agencies.

The lawsuit also seems to have been hastily prepared. One allegation was that, because the school claimed on its website to be a safe environment for children, WHC had misled the public. But court filings show that Racine mistook a different preschool’s website for the one belonging to WHC.

The narrative in Racine’s complaint about “Jenny” was particularly misleading. After describing Jenny’s ongoing behavioral issues, Racine wrote, “Despite knowing that the child had been exposed to Silverman for nearly two years and despite numerous warnings and concerns raised about Silverman’s behavior with the children, Jensen reported to CPS that she suspected the child’s father was abusing her.”

This claim, which was echoed in media coverage, made it sound as if the school had deflected from its own mistakes by baselessly accusing a parent of abusing his own child. That would indeed be outrageous if it was true. But it isn’t what happened. Jenny’s art project raised red flags in April 2018. Jensen was required by law to report any suspected abuse — and she did. The accusations against Silverman from Jenny’s parents came four months later. And when informed of those complaints, the school immediately suspended Silverman. It then fired Silverman when the CFSA determined that the complaints were substantiated.

Moreover, the allegation that Jensen ignored multiple “warnings and concerns” about Silverman sounds damning only if you don’t know that three law enforcement agencies ultimately reached the same conclusion Jensen had — there was no persuasive evidence that Silverman had abused any children.

Racine’s office put out a press release announcing the lawsuit, as did Cohen Milstein. Racine himself also gave an interview about the complaint to a local TV station. That brought yet another round of national media coverage accusing Silverman of abusing children.

Jeffress and Sarah Fink — Silverman’s other attorney — sent a furious letter to Racine. “Your office’s actions in filing the complaint were irresponsible,” they wrote. They demanded that Racine revise his complaint to omit Silverman’s name, and to include that he had been cleared.

They never received a response. Racine, who is now a partner at the law firm Hogan Lovells, did not respond to my requests for an interview.

WHC eventually settled with Racine’s office. The school admitted to several administrative violations, the most substantive of which was running a summer camp program without a proper permit. That allegation didn’t involve Silverman at all. The school settled for $900,000 on that claim, which was broken up into a payment to the city, a payment to a charity, and refunds for parents who had sent their kids to the camp. The settlement did not include any admission that abuse took place at the school.

Silverman later filed an open records request with the D.C. Attorney General’s Office for any documents related to Racine’s investigation. Given the way Racine had openly accused him in the lawsuit, Silverman was desperate to see what evidence he could have had. The office responded that the case file had over 800,000 records, and that Silverman would have to pay more than $1 million to see them.

The settlement with Racine meant the parents’ lawsuit was the only remaining litigation left. In February 2021, the elite law firm Paul Weiss joined Cohen Milstein’s lawsuit on behalf of the parents. Former White House counsel and U.S. attorney Karen Dunn would personally represent them. Dunn directed the presidential debate preparation for Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, and Kamala Harris. She left Paul Weiss after the firm entered into a much-criticized agreement with the Trump administration.

Patrick Fitzgerald’s firm also joined the lawsuit. Like Dunn, Fitzgerald is one of the most powerful, well-known attorneys in the country. He’s a former federal prosecutor who took high-profile terrorism cases — including prosecuting Osama bin Laden —and was the special counsel who investigated Scooter Libby. He was also hired by Michigan State University to investigate the sexual abuse claims against Larry Nassar. Fitzgerald is currently representing James Comey.

By this point it had been more than a year since Silverman was cleared by law enforcement. Yet two of the most powerful attorneys in the country had just joined a lawsuit that presupposed his guilt. And they had joined the suit despite numerous red flags that should have called its legitimacy into question.

To support its complaint, for example, Cohen Milstein hired expert witnesses known for defending the controversial “recovered memory” therapy techniques that resulted in false charges during the ritual sex abuse panic decades ago.

One of those experts, Daniel Brown — a longtime proponent and defender of repressed or recovered memory therapy — filed a specious affidavit. Brown didn’t claim to have helped any of the children recover suppressed memories of abuse. Instead, his affidavit argued that a therapist’s failure to recover such memories does not necessarily mean that there was no abuse.

WHC hired Maggie Bruck, a child psychiatrist with Johns Hopkins University, who has studied sex abuse cases, to assess the interviews conducted with the children. Bruck told me she is barred from speaking about specifics in the case, but did offer this comment: “I’ll just say this: All the indices I’ve seen in previous false accusation cases were present in this case.”

The synagogue also consulted Ken Lanning, a former FBI agent with 30 years of experience as a behavioral analyst specializing in crimes against children. In his affidavit, Lanning said that Silverman “does not fit the distinct patterns of an acquaintance child molester, and it is more likely than not that Mr. Silverman did not sexually abuse the plaintiff children.” Lanning, too, told me that he was prohibited from speaking publicly about the case.

Even as it became increasingly clear that the evidence against Silverman was weak, the public accusations got more lurid. In January 2023, in an unsigned letter published online, parents of the alleged victims claimed that Silverman had “penetrat[ed] their private parts with his fingers,” made toddlers molest one another, and “exposed his genitals to them.” The letter added that some kids had also “implied, by using descriptions such as ‘vanilla pee,’ that he ejaculated on or in front of them.”

These were by far the most detailed and disturbing accusations to date. But experts I spoke to expressed skepticism that 2- to 3-year-old children would use a term like “vanilla pee,” though they said it was at least possible, if improbable, that a four year old might.

It’s worth noting that the most lurid allegations weren’t made public until five years after they allegedly happened, and well after Silverman had been cleared police. And while cautioning that there will always be exceptions, other experts who study predatory behavior also agreed with Lanning that Silverman just doesn’t fit the profile of most abusers. Sexual predators are risk averse, so they tend not to abuse children in public spaces where they might be caught. “Child predators tend to isolate kids,” says Emily Horowitz, a sociologist at St. Francis College in Brooklyn. “Another red flag here for me is the allegation that Mr. Silverman would take a job at a preschool to access kids. That isn’t typically how predators operate. Another one is that he would abuse groups of kids at the same time. That also just isn’t consistent with what we know. But it is a common theme in false allegations.”

About a year after I started reporting this story, Silverman called me to say he had been withholding something from me — something that could be powerful exculpatory evidence: He has two tattoos of well-known cartoon characters, both in places the children would likely have seen had he committed the kind of abuse alleged.

“It was a stupid, drunk thing I did as a teenager,” he said. He said he hadn’t told me this earlier for a couple reasons. First, he realized that it’s a little weird for a grown man to have tattoos of cartoon characters. And second, while he has been cleared of wrongdoing, there’s nothing preventing law enforcement from charging him at some point down the road. He was afraid that if his tattoos became public knowledge, the parents or therapists might inadvertently transfer that information to the children, who may then think they remembered seeing them.

It sounds paranoid, but experts say his fear is justified. “I don’t blame him at all for worrying about that,” says Lana. “I would advise him to keep those details to himself.” Silverman agreed to let me include this information, but without mentioning which characters the tattoos depict.

Because the CFSA and lawsuits are sealed, it’s impossible to say for certain that no children mentioned seeing any tattoos. But it seems likely that if any did, it would have been the sort of slam-dunk evidence that would have resulted in criminal charges.

In March 2023, the saga took an astonishing turn.

Michael Dolce, the Cohen Milstein partner who led the firm’s lawsuit and public relations campaign against Silverman — the man who had smeared Silverman as a child predator to numerous media outlets — was himself arrested on child pornography charges.

Investigators said they found nearly 2,000 sexually explicit images and videos of prepubescent children on Dolce’s laptop. According to law enforcement, the attorney was in bed downloading more images when the police broke into his apartment.

Dolce had publicly said that his work on sex abuse cases was motivated by abuse he himself endured as a child. This isn’t surprising. There’s ample evidence that many abusers were molested themselves. There’s also evidence that some survivors consume child porn as a coping mechanism, or a misguided form of therapy. “I can’t tell you how many times we found a bad guy, and then learned that they had been abused too,” Epner says.

Still, the arrest was a jaw-dropping revelation. The relentless attacks on Silverman for abusing children — and against the WHC for failing to protect those children — had been led by a man who was himself sexually exploiting children the entire time.

Shortly after the accusations against Dolce went public, the parents of the alleged victims settled with the school. The terms of that settlement have been sealed. Two experts who consulted on the case told me they were ordered to destroy all of their records. In December 2023, Dolce was sentenced to four years in federal prison.

For several years, Cohen Milstein had been putting out press releases about Silverman’s alleged crimes. They released a statement when they filed their initial lawsuit, when Racine filed his own suit, and another celebratory press release when that lawsuit was settled. The firm’s website also tracked media coverage of the case. But when the firm’s clients, the WHC parents, settled their lawsuit in the wake of the allegations against its partner, the firm did not put out a press release. There was also no media coverage of the settlement.

There’s no longer any mention of Silverman’s case on the Cohen Milstein site at all. A Google search still returns some court filings, but clicking on those documents now brings a 404 error.

In response to a list of questions, a Cohen Milstein partner responded with this statement:

“Cohen Milsten is proud of its advocacy for families going through incredibly traumatic circumstances and of its work holding institutions accountable for creating safe environments. Our most deeply held belief is that everyone has the right to be heard, and our legal system is the best way to ensure universal access to justice.”

Part Seven

As we chatted over coffee at a Manhattan cafe in the summer of 2024, I asked Silverman about the status of his custody fight.

“It’s over,” he said.

Over the course of my interviews with him, Silverman was especially prone to break down when he spoke about the toll the accusations have taken on his kids. This was one of those times. He stammered, paused, and wiped away a tear.

“I had to give up.”

Silverman composed himself. After law enforcement cleared him, he said, the judge in his custody case had revoked the protective order. But Rebecca then filed again for sole custody. With the CFSA report still hovering over him, his attorney told him he wasn’t likely to win.

“I also just don’t have the money to pay another lawyer,” he said. “Even if I could somehow win in court, the boys have been taught to want nothing to do with me now.”

Silverman moved on to talk about the other victims in his case. “I worry about D.J.,” he said, referring to Jensen, the director of the preschool. “She was such a brilliant educator and such a great advocate for kids. Her life was ruined because of all of this, too.”

Silverman even expressed empathy for the parents who had accused him. “I understand the impulse to protect your kids,” he said. “I shudder to think of what I’d do if I thought someone had harmed one of my sons. But I hope they’d consider the fact there was an investigation that inspected everything I own and involved just about everyone I know, and they found no evidence that I’ve done anything wrong. And there was a lot of pressure on them to find something. I hope they’ll think about the fact that I came to you and asked you to look into my story. I can’t claim to know how a predator thinks, but I would think a predator who had just gotten away with sexually abusing 15 kids would not go to a journalist and open his life up to further investigation.”

He paused again, and looked pensively around the cafe.

“I worry most about those kids, though, “ he said, now referring to his accusers. “They’re going to spend the rest of their lives thinking they were sexually abused when they weren’t. That does real harm too. They’re going to be dealing with this trauma, this completely unnecessary trauma, for the rest of their lives.”

Experts confirm Silverman’s fears, here. The kids who wrongly accused caretakers, parents, and grandparents during the 1980s and 1990s suffered psychological and emotional damage well into adulthood. In the documentary Witch Hunt, which recounts wrongful convictions in Bakersfield, California, one accuser said he couldn’t bathe his son because it made him think about the harm he’d done when he falsely accused his own father.

But cases like Silverman’s may also do broader harm. The WHC preschool had two male teachers prior to Silverman — Alex Bailie and one other man. Both were fired. Bailie says he was fired for leaving the classroom to report an incident. According to sources familiar with the school, the other male teacher was fired after a complaint from parents. Former staff and parents say both were excellent teachers. “I don’t think either would have been fired if they had been women,” says Francine.

Child development experts say kids benefit from mixed-sex childcare environments — that it’s healthy for kids to have both male and female preschool workers, teachers, and counselors. But there aren’t many men interested in those positions. There are almost certainly traditional gender-related reasons for that, but cases like Silverman’s don’t help.

“There’s data showing that before the ritual sex abuse panic started in the 1980s, more men were starting to go into childcare,” says Horowitz, the sociologist at St. Francis College. “By the 1990s, that trend just stopped completely.” According to labor statistics, the percentage of childcare workers who were men was at about 6.2 percent in 1976. By 1996 it dropped to 2.1 percent. By 2018, as the ritual abuse panic subsided, it was back up over 6 percent.

“Any man who works in childcare is putting his life on the line,” says Lana, the metro-area sex abuse investigator. “I’ve told my own sons to never, ever be alone with any kid who isn’t your own. Maybe that sounds extreme, but I’ve seen it too often. As a society, we just don’t trust men around kids. And it only takes the slightest bit of suspicion to ruin your life.”

Earlier this year, a relative agreed to give Silverman some money specifically to hire an attorney to challenge the CFSA findings in his case. The attorney met with the office in May. At that meeting, a CFSA representative offered a compromise: If Silverman dropped the appeal, the office would change the results of its 2017 investigation from “substantiated” to “inconclusive.”

According to the CFSA website, an “inconclusive” designation means the agency found “credible evidence that a child was abused or neglected but the person in question cannot be proven to be the maltreator.”

If Silverman proceeded with the appeal, however, the findings would remain unchanged, and the case would proceed to a hearing to adjudicate the matter.

He decided to proceed to a hearing. An “inconclusive” finding was not the vindication he was looking for. Such a finding also meant that Silverman’s name and the allegations would still remain in a D.C. register of alleged child abusers.

On May 13, Silverman was attending a criminal justice conference in Philadelphia sponsored by the Quattrone Center at the University of Pennsylvania’s law school (disclosure: I’m a journalism fellow at Quattrone). He was preparing to give a presentation about his case when he received an email from CFSA.

He had won. The email explained that because law enforcement investigators did not find sufficient evidence to charge him, because the findings were based on the work of a single investigator, and because of the time that had passed since the allegations, “the CFSA Office of General Counsel does not believe we have sufficient evidence to go forward or prevail” at a hearing.

The four accusations that the CFSA officer had determined to be “substantiated” in 2018 would be changed to “unfounded,” a finding that meant the accusation has “no basis in fact, was made maliciously or in bad faith, or for which the person in question was not the maltreator.”

After seven years, Silverman had finally been vindicated. “I had to run out of the conference room when I saw the email,” he says. “Tears were streaming down my face.”

The letter did not include an apology, nor did it include any explanation for the initial findings that upended Silverman’s life.

After an initial burst of joy and relief, Silverman says he started to reflect on the case and the profound, irreversible impact it had on his life.

This, he says, is when the anger started to settle in. “I don’t understand why they were willing to downgrade these findings that had ruined my life just so they wouldn’t have to hold a hearing. I don’t understand why after that, all it took was me pushing for a hearing for them to completely reverse themselves. What evidence could they have possibly had if they could just so easily disregard it?”

Silverman says he hadn’t previously challenged the CFSA findings because he had to prioritize his legal fight on the criminal investigation and his custody dispute. After he was cleared by police, he asked CFSA to revisit its conclusions but never heard back. It was only after he paid $5,000 to a lawyer that the office revisited its findings. Afterwards, he contacted the office. “I told the woman who took my call that there should be an automatic review of substantiated findings if a subsequent law enforcement investigation doesn’t result in criminal charges,” he says. “She told me that sounded like a good idea. They hadn’t thought of that before?”

“I know it isn’t healthy, but I can’t stop thinking about all the damage that could have been prevented if they’d just gotten it right the first time,” he says. “My family wouldn’t be still living in hiding.” And, he adds, “I wouldn’t be worried about my parents passing without ever getting to see their grandsons again.”

Today, an internet search of Silverman’s name still brings up a panoply of stories about the accusations against him, but no mention of the fact that every government body to investigate those accusations has now cleared him. For a case in which the system “worked,” it has left a trail of destruction in its wake. This raises some important questions: What could have been done better? What do we owe the accusers, and what do we owe the accused?

CFSA and law enforcement obviously had to investigate Silverman, and once he’d been accused, the school had little choice but to fire him. Silverman himself says he wishes O’Brien or someone else in law enforcement would have gone farther — perhaps by declaring him innocent, or apologizing for what he’d been through. Former federal prosecutor Mitch Epner, while sympathetic to Silverman, disagrees. “A prosecutor’s job is to seek justice if there’s sufficient evidence of guilt,” he says. “If we start asking them to declare people innocent, you’re going to create a different set of problems.”

The federal government does allow acquitted defendants to recover compensation, but only if they can show that they were prosecuted in bad faith, a standard that renders the policy all but useless. There’s no compensation for merely being investigated — even if, like Silverman, it resulted in a debt he’ll probably never pay off.

“We think that when the system clears someone’s name, everything has worked the way it was supposed to,” says Henry. “But it doesn’t restore those people where they were before the accusations. Not even close.”

The media certainly deserves some blame, particularly those outlets that published sensationalist coverage, pushed a coverup narrative, and never seemed to entertain the possibility that Silverman might be innocent. It also seems likely that some of that coverage was influenced by Cohen Milstein.

Racine’s lawsuit was perhaps the most reckless and avoidable action by a public official. It was based entirely on allegations that three law enforcement agencies found no evidence to support. And it certainly didn’t need to gratuitously mention Silverman dozens of times.

The CFSA investigation is a more difficult problem. While it seems likely that the initial investigator was well-intentioned, the one-day investigation seems likely to have been driven at least in part by an overburdened, understaffed office. “If you want to know a person’s priorities, show me their budget,” says Epner. “We need to fund these offices sufficiently, so that an investigator can take more than one day to conduct an investigation.”

But more broadly, there are no easy answers when it comes to how to balance taking accusations seriously with respecting the rights of the accused. Even when the criminal justice system functions as well as can be expected, it can still wreak a lot of destruction.

In the end, for all he’s been through, Silverman’s friends say it’s his lost relationship with his sons that bothers them most.

“Back when we were young and single, Jordan took a parenting class,” says Maureen O’Dea. “He didn’t even have kids at the time! He wasn’t dating anyone. He said he just wanted to be ready to do a good job when the time came. I can see how someone would think that’s strange. But once you know Jordan, it makes perfect sense. I think he sees it as his mission to make sure no kid ever has a bad childhood.”